A Partial Guide to Camp: On the Loo

New Orleans bounce performer Big Freedia created her installation, AZZ EVERYWHERE, to express ''the power of self-confidence and the power of the 'Booty.'''

Editor's Note

Last October, Laurence Ross began his ''Partial Guide to Camp'' reflecting on Southern Decadence and Nicki Minaj. He continues with a look at Booty's Street Food's Bywaterloo.

When a prospective customer takes a virtual tour of any restaurant on the internet, the bathroom is never in the picture gallery. The bathroom is meant to be kept out of consciousness. Both too vulgar and too banal, the bathroom is a near-taboo element of the everyday. The bathroom is not the “appropriate” bodily function to highlight in a dining scenario. A dining experience is meant to focus on consumption—and nothing else.

Bywaterloo calls into question this expectation/norm. The rotating monthly art installation takes place inside of Booty’s Street Food in the Bywater, but not in the restaurant proper. Bywaterloo takes place in the bathrooms, which, according to Booty’s, are “utilitarian spaces … ripe for interpretation, inspiration and reflection.” Is a bathroom inherently interesting? Perhaps that interest lies in the perspective/vision/eye of the beholder. With white walls, white toilet, and white tiled floor, a bathroom is often a whitewash: a cover-up, a glossing over. The bathroom (at least the generic bathroom) is not a place where one lingers. You powder your nose and you return to your table, just as if nothing has happened at all. The bathroom, especially in a restaurant, is a non-event, a non-happening.

And, in fact, one of Bywaterloo’s first bathroom installations by Shannon Slane was overwhelmingly white. My usual approach is to read the artist statement after I view the art, just as my usual approach is to read the forward after I finish the novel. I want to perform my own critical framing before any other voice enters the conceptual space; I want the standard for the experience to be not the artist’s or another critic’s, but my own. However, unlike a novel, with which you can quickly flip through any introduction and arrive at the fiction itself, a bathroom presents the complication that there might be someone else inside. With a bathroom, the door may be (however temporarily) locked. This lock produces a forced delay—not artificial, exactly, but not germane to the average art experience.

While I waited during that first opening in January, I read Slane’s artist statement/narrative on the bathroom door:

Frederick and Thalia live in blank walls. You might have noticed them before, as they're intensely curious about private moments and peek their heads out every once and awhile to observe.

Thalia is fond of listening to you sing to yourself, while Frederick enjoys the faces you make, particularly in the mirror. When they're not watching you from the starkness of plaster or marble or simple white paint, they busy themselves with collecting the stray bits of color that their bleak environments absorb, and then beam them back out into the world.

Either one would be delighted if you addressed them the next time you find that you are staring at the walls of an empty room, instead of just yourself.

Here, we are prepped for white. Before I enter, I am expecting an installation that is subtle. I am tuning my brain to a frequency that will be able to distinguish the nuanced variations between shades of eggshell and ivory, cumulus and cotton. I am expecting figures lurking in the shadows of the room, as specter-like as the woman in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper.” But when I finally enter the bathroom, I discover that Frederick and Thalia are enormous unicorn busts, bursting forth from opposite white walls, each shooting a spectrum of rainbow-colored rays from the tip of a braided horn.

This is the power of the Camp aesthetic: the ability to set up an expectation, and then subvert it, the ability to transform a bathroom into a “bathroom,” the ability to take a stabilized identity and destabilize it. To work with the Camp aesthetic is to work with the process of queering. Queer (v.): to make other, to collapse an accepted standard, to deconstruct a constructed identity, to expose identity as fluid. Moe Meyer, in his introduction to The Politics and Poetics of Camp, states: “What ‘queer’ signals is an ontological challenge that displaces bourgeois notions of the Self as unique, abiding, and continuous while substituting instead a concept of the Self as performative, improvisational, discontinuous, and processually constituted by repetitive and stylized acts.” And while Meyer (and many other critics of Camp) insists that what is displaced is the set identity of an individual, if we permit “Self” to expand, to also include objects and concepts, the Camp aesthetic and the act of queering can challenge us on many more fronts. After all, how different are the questions what is a bathroom, what is a unicorn, and what is a sexuality?

Bywaterloo, a rotating monthly art installation, takes place inside the bathrooms of Booty’s Street Food in the Bywater.

It is probably worth noting at this point that while there are two bathrooms at Booty’s, they are both gender-neutral. In the middle of each bathroom door, where we would expect to see “men’s” or “women’s” or some symbol representing one or the other, there is an image of a figure that is split halfway down the middle—half short hair, half long hair; half dress, half pant. I’ve watched people stand between the two doors, scrutinizing the identical signs, trying to determine which they are most suited to enter. I’ve seen people open one bathroom door and close it right away, apparently deciding that what is inside is not (meant for) them.

Though Susan Sontag defines Camp as a “taste” or “sensibility,” Meyer expands (and rebuts) Sontag’s canonical definition, saying, “Camp is not simply a ‘style’ or ‘sensibility’ as is conventionally accepted. Rather, what emerges is a suppressed and denied oppositional critique embodied in the signifying practices that processually constitute queer identities.” Allow me to divest a layer of Meyer’s academic drag: Meyer believes that Camp is more than a sensibility, that Camp is inherently and necessarily critical of cultural standards/identities, and that the Camp aesthetic queers those standards/identities. And this is precisely the work Bywaterloo asks of the audience: to critically examine what constitutes the standard identity of a bathroom, an art installation, a gender.

One of the project’s most recent artists is New Orleans bounce performer Big Freedia. Her installation, AZZ EVERYWHERE, shares conceptual space with Frederick and Thalia, though is, in a way, its visual opposite. Rather than bright lights and white walls, Big Freedia’s installation is a montaged rendering of (in her words) “the power of the ‘Booty.’” There are airbrushed paintings of cartoon-like booties in jeans, photographs of naked booties, photographs of booties in underwear, and photographs of booties in underwear designed to enhance and enlarge the appearance of the wearer’s booty. These representations of “Booty” are framed in an atmosphere supersaturated with lamé fabric, purple shag carpet, Mardi Gras beads, and Christmas ornaments both phallic and ovular in nature.

The installation by Lauren Marie Cappello featured a skeleton seated on a non-functional toilet directly opposite the working toilet.

If this all seems a little overboard, the very notion of “too much” is ingrained in the very foundation of Camp. Oscar Wilde, arguably the origin of the modern Camp canon, writes in his play, A Woman of No Importance: “Moderation is a fatal thing … Nothing succeeds like excess.” A century later, David Bergman, editor of the anthology Camp Grounds, champions Judith Butler as Camp’s most influential political advocate and borrows Wilde’s quote for scaffolding when he writes: “For Butler nothing succeeds in subverting the straight like excess.” And yes, “straight” in this context is referring to sexuality, but it need not only refer to sexuality. Camp’s ability to subvert extends beyond challenging the heteronormative. Nothing succeeds in subverting the straight, the banal, the ordinary, the standard, the normal, like excess.

Camp requires a nuanced palate for recognition and perhaps an even more nuanced palate to appreciate. Because of Camp’s frivolous appearance, the sincerity of the aesthetic often goes unseen. It took Bergman ten years to find a publisher for his anthology of Camp essays. In 1979, the only publisher interested (Urizen) was a small avant-garde operation that produced critical works on topics no one else would touch—like excrement. Bergman’s co-editor at the time, Karl Keller, said that Urizen wanted “to do for us what they did for shit.” But in the end, Urizen did not publish the book. In effect, Camp was deemed shittier than shit. And it took another ten years before that reception would change.

To sit on the toilet in Big Freedia’s “bathroom” is to be presented with a mask, a pair of enormous yet pupil-less eyes. In this space that is “supposed to be” private, the participant is never quite alone. In this space that so often contains the most sterile of décor—a sprig of plastic pastel flowers, a few shoots of bamboo, some innocuous pastoral painting, not a thing to make one pause or linger—we are asked to consider our Self. We are asked to consider our Self not in the manner of looking in a literal mirror, adjusting a strand of hair, fixing a collar, reapplying a fresh coat of lipstick, but to consider our Self as a multifaceted being, an identity that is not “male” or “female,” an individual free of labels and constriction, free to enter (or not enter) whichever bathroom we wish, whenever we wish.

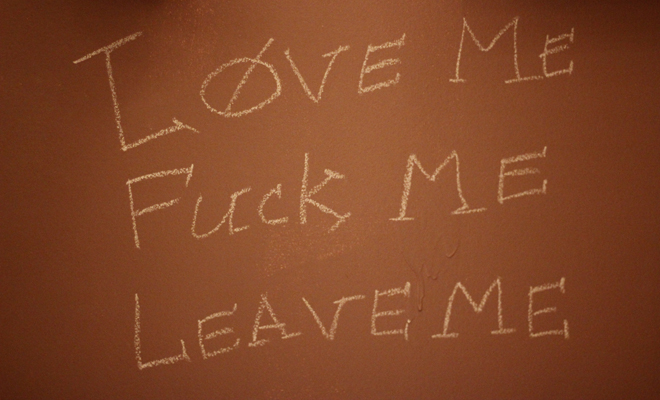

And if we consider “Self” to be a variable, a person/object/concept in flux, Camp calls not just gender/sexuality into question, but all identities. Charles Ludlam, author of Ridiculous Theatre: Scourge of Human Folly, writes: “The value of camp, the ability to perceive things in this unique way, is that it turns values upside down.” A variable, mathematically speaking, is a figure with a specific value but a value unknown. X is a variable you work towards, contemplate until its identity is revealed. And then, in the next equation, the value of X is different. The value of X is always in flux, the nature of its identity up for grabs. Camp highlights this variable value, this identity-in-flux. A private bathroom is no longer private. A bathroom becomes a “bathroom,” a space that we are undeniably sharing with another presence. (Slane’s unicorns, for example, or Big Freedia’s big eyes. A February installation by Paige Valente presented an omniscient voice scrawled in chalk, a director of sexual acts, while a March installation by Lauren Marie Cappello featured a skeleton seated on a non-functional toilet, posed/poised in direct opposition to the functional one.)

There is one final aspect of Bywaterloo to mention, and it is no trivial detail. Paired with each bathroom installation is a custom cocktail. Both Camp and alcohol are mediums of transformation, of making us see differently, of blurring lines/identities, of calling into question what is “real.” To experience a piece of art is, at its best, to experience a type of transformation. But the Camp aesthetic very well may require a certain attention to detail, a certain (critical) framework to recognize its presence. It may take a willingness of submersion/subversion to “see” what is right in front of one’s eyes. As Susan Sontag says in her essay, “Notes on Camp,” “Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style—but a particular kind of style. It is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” In other words, Camp is an aesthetic that presents to us the world in an altered state—which is why the pairing of Camp art and alcohol is so apropos. In an altered state, we are reminded that most truths and certainties are a matter of perspective. In an altered state, a “bathroom” serves as a type of funhouse mirror in which we can scrutinize/analyze the makeup/make-up of our cultural constitutions.

Text-based artist Paige Valente scrawled a list of commands in chalk as part of her installation in February.

Editor's Note

Big Freedia's installation remains on view until Thursday night. A new batch of installations will open on Saturday, May 11 at Booty's Street Food (800 Louisa Street) in New Orleans.