True Colors: Thornton Dial's Hard Truths

Thornton Dial, Green Pastures: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly, 2008. Cloth rags, rubber-coated copper wire, wire, screws, enamel on canvas on wood. Courtesy the artist and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta. All photos by Stephen Pitkin, Pitkin Studio.

By way of introduction, his list of materials includes: corn husks, frying pans, cloth rags, turtle shells, peach baskets, vines, soil, cow bones, tire irons, broken glass, mop cords, car fenders, and steering wheels. And these are his basic works. The more adventurous pieces might put to use such objects as dead cows, goats, rats, birds, “other found materials”—which, brilliantly, he never names—and the element of fire itself, here a material as much as it is a process. He once burned a painting—not to make a point, as a performance artist might have imagined—but to achieve a texture, a residue, that the paint alone could not provide.

Currently on view at NOMA, the exhibition is entitled "Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial"—a gesture to Dial's interest in the poor, rural, and oft-forgotten corners of the South, of which he is a native and from which he draws his inspiration. Dial's works present a range of provocations, not least of which is their size: working in a variety of media, often in extremely large-scale format, his works occupy the majority of each wall on which they hang or the bulk of the room in which they are installed, demanding the viewer's full attention, respect, and response. Self-taught and often labeled an “outsider artist,” Dial has withstood considerable controversy during his career, which began most notably with a misleading portrayal on 60 Minutes in the 1990s, a difficult period that Joanne Cubbs details in an essay in the exhibition catalogue and which was later explored in the documentary film Mr. Dial Has Something To Say (available here).

The current exhibition, a retrospective organized more according to political and historical ideas than to chronology or medium—sections of the gallery are themed “The Rural South,” or “Modern Politics”—offers selections from the late 1980s until the present day, offering a window onto the maturation process of Dial's work. The themes reveal much about Dial's interest in poverty, racism, historical and contemporary injustice, and American idealism, and do much to engage the viewer who may be unfamiliar with his work, but given the formal strength of the work, the curation could as well have taken place along formal lines.

One aspect of Dial's work in nearly all its genres, his drawings perhaps excluded, that strikes even the casual viewer is the sheer muscularity and physicality of his work, which brings opportunities to explore questions of meaning within the color, line, and texture. This is perhaps most immediately evident in his floor installations, such as Old Water, 2004, a panorama of driftwood, barbed wire, scrap metal, and dead birds covered in blood and wrangled into awkward positions, a work that eerily presages the destruction of both Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill in its depiction of mauled wildlife. So, too, in Lost Cows, 2000-2001, a cathedral-like structure of bleached cow bones formed from the remains of cattle Dial himself once owned—a work whose viscerality transcends its biography.

But his colors and lines are equally at work: the confrontation between, for instance, the thin patches of red, white, and blue against the drab and muddy greys and browns of Lost Americans, 2008, quietly ironizes the colors of the flag under which these subjects—a man and a woman on a farm, far from any entitlement or enjoyment of the rewards of liberal democracy—labor. Dial's palette is often muted, almost morose in its hues and tones; when he does use color he tends to do so in a way that calls attention to the elements, ideas, or materials already under scrutiny. The birds on the reverse side of the installation Everybody's Welcome in Peckerwood City, 2005, are splashed with scarlet red, standing out against the browns of the gutted wood and echoing a moment on the frontal side of the piece, a splash of red on the lintel: a quiet homage to the night of Passover, when the Israelites painted their doors in lamb's blood to shield their firstborn against the angel of death.

Thornton Dial, Trophies (Doll Factory), 2000. Barbie dolls, stuffed animals, plastic toys, cloth, tin, wood, rope carpet, Splash Zone compound, oil, enamel, and spray paint on canvas on wood. Courtesy the artist and Jane Fonda.

Similarly, Dial's use of line achieves dramatic results, as in Trophies (Doll Factory), 2000, a riotous tableau of Barbie dolls escaping fiercely hungry stuffed animals, the dolls spray-painted silver and gold against a dark, nocturnal backdrop. Compositionally reminiscent of Robert Gordy's stepladdder-ascending figurines in works such as Boxville Tangle #4, one wonders whether Dial was aware of Gordy's work—but even if not, the lines impart a nervous energy into the composition, and lead one to suspect that the end of the tension will not play well for any of the entities involved. His understanding of the impact of a single line is perhaps at its most visible in Green Pastures: The Birds That Didn't Learn How To Fly, 2008, a somber meditation on horizontality with vertical punctuations, and in Construction of the Victory, 1997, and Victory in Iraq, 2004, a more politically critical work in which the dominant “V for victory” transects a ragged landscape, a ground-level impression of what the conflict left behind: barbed wire, rope, debris, and the implied dead.

Victory in Iraq, 2004. Mannequin head, barbed wire, steel, metal grating, clothing, tin, electrical wire, wheels, stuffed animals, toy cars and figurines, plastic spoon, wood, basket, oil, enamel, spray paint, Splash Zone on canvas on wood. Image courtesy the artist and the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

In other works Dial suggests that line and form can, in a manner approaching latter-day Cubism, transform the perspective and understanding of an event. In Valley Creek Disaster Area, 2004, he renders the aftermath of a tragic flood in his native Alabama from a bird's-eye view: an aerial exploration, eerily impressionistic, of a ruined landscape all too reminiscent of images that would stream out of New Orleans only a year later. Conflicts, disasters, and loss have long been sources of engagement and response for artists, and each has its own iconic dimensions and ways of being portrayed: the trench-eye view of World War I-era painters, for instance, or more recently, the film Lebanon (2009), which takes place entirely within the interior of an Israeli tank during the early days of the Lebanese Civil War. Such novel means of representation have twofold effect: they open and expand our sensibility to the lived experience on the ground, and they offer a reexamination of the political stances and attitudes that lead to those disasters in the first place.

Even so, the tensions between formal and political aspects in Dial's work are not always resolved. In one of the central pieces near the end of the exhibition, Driving to the End of the World, 2004, a five-part piece in which Dial has eviscerated an abandoned rusted car and used its component parts to construct a critique on America's oil habits, he caricatures an Arab sheikh, complete with Saudi headdress. The effectiveness of this critique is uncertain: as visitors to the exhibition would, presumably, be driving their cars to and from the museum, it remains an open question the extent to which visitors would leave feeling the sharpened tip of the work.

More to the point, however, is the appropriateness of this particular stereotype. Arab oil barons may be partly responsible for the conditions that draw Dial's outrage, but are not, equally, the suited executives of the oil and gas companies based in Louisiana, those executives who continue to decimate the state's fragile coastline through drilling and exploration, and whose economic superstructures contribute to the modern-day continuation of the hardscrabble lives he elsewhere depicts? Dial may well be satirizing all stereotypes, but if so, the satire is too subtle, leaving the unanswered question: why travel so far abroad to levy a critique, especially given his skill at skewering social mores, impoverished regionalisms, and the vagaries of American history? Aesthetically, the injunction is clear: rare are our great machines laid open before us like cadavers on an autopsy table, and we have much to learn from their dissection. Politically, however, the work could have traveled further by staying closer to home.

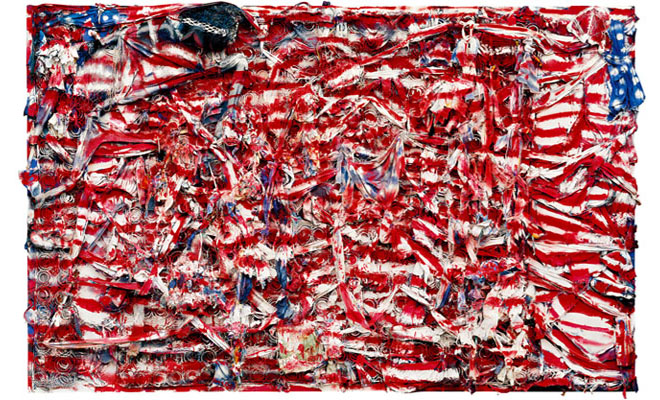

Don't Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got To Tie Us Together, 2003. Mattress coils, chicken wire, clothing, can lids, found metal, plastic twine, wire, Splash Zone compound, enamel, spray paint on canvas on wood. Image courtesy the artist and the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

When it works—where the formal and the political tensions inherent in the work do resolve as in Don't Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got To Tie Us Together, 2003—Dial's true colors emerge. And these works alone are worth the price of admission, in their playfulness and their invention, their suffusions and their implications, and ultimately, their simple truths. Perhaps no work is more beautiful than the surprisingly personal Surviving the Frost, 2007, a tribute to his late wife: a piece made of plastic, enamel, stone, wire, and rails—again, these improbable, hard materials bound and worked by hand—in which Dial has woven delicate flowers springing up from the bare ground, illuminating the canvas in color. A haunting, ethereal way to close the exhibition, the piece seems to suggest a note of hope: that despite difficulty, loss, and hardship, despite the differences that preclude understanding and reconciliation, one experience still binds us together even across the greatest of all divides. As Philip Larkin once wrote, “what survives of us is love.”

Editor's Note

"Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial" is on view through May 20, 2012, at the New Orleans Museum of Art.