Anything but Decorative: Robert Gordy and Tina Girouard

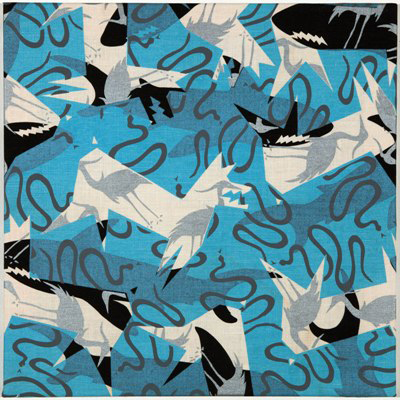

Tina Girouard, Animals, B, 1984. Silkscreen on cotton. Courtesy the artist.

To fully apprehend “Patterns and Prototypes,” the exhibition of works by Robert Gordy and Tina Girouard on view at the Contemporary Arts Center, an old schoolyard game is surprisingly useful. Take a word—any word will do but a personal favorite works best—and repeat it over and over until it begins to lose its sense, the sheer act of its repetition gradually untethering it from its referent in the mind. Continue to utter it until it has lost all meaning whatsoever and has become a mere sound. The effect is jarring: words floating free of their concepts, sounds hovering aimlessly above the objects with which they once danced.

Jarring, yes, but instructive. By inviting us to reconsider the relationship between words, sounds, structures, and concepts, this little game offers a readily available opportunity both to approach certain boundaries of understanding and to return from them, once the dust has cleared and the word for “table” has finally, after an hour or so, regained its legs. These boundaries make a startling appearance in “Patterns and Prototypes,” explored in diverse and striking ways by both of the artists on view.

The show, occasioned by the 35th anniversary of the CAC, aims to honor Gordy and Girouard's involvement in the early development of the Center in the 1970s and ’80s. Presenting about two dozen works by each artist during roughly that time period (Gordy from 1963-1985 and Girouard from 1971-1989), it provides a snapshot of each of the artists' work during a critical moment not just for his or her own development but also for the Pattern and Decoration movement, of which they were both a part. Rejecting both Minimalism’s austerity and the reigning modernist proscription of all things “decorative,” the movement's leading figures—Robert Kushner, Valerie Jaudon, Joyce Kozloff, and Miriam Schapiro—were largely based in New York and California, with their activity reaching its crescendo in the late ’70s and early ’80s. (Girouard had moved to New York from Louisiana in the 1960s, while Gordy worked in New Orleans for much of his life until his untimely death in 1986.)

Gordy's work is largely characterized by bold lines and strong forms, stylized but clearly recognizable figures, and a declared interest in the space of the canvas as a window into a much larger imaginative realm. Stylistic comparisons to Keith Haring, who would begin exhibiting widely in the 1980s, as attention to the Pattern and Decoration movement was waning, are not out of place; many of Gordy's figures seem to shiver and quake like Haring’s radiant babies. (It is worth noting that Gordy's later work, here seen in Two Female Figures, 1982-1985; Making a Garden, 1982; and Figures in a Landscape #1 (Pools), 1981, softens his line and his palette into a calmer, more sanguine expression of his ideas.)

Robert Gordy, Boxville Tangle #4, 1972. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans. Gift of the Roger H. Ogden Collection.

Gordy's large-scale acrylic painting Boxville Tangle #4, 1972, for instance, depicts a progression of silhouetted female nudes (curiously lacking arms and feet, but enjoying ample breasts and buttocks) climbing through space at diagonal angles, suspended within a scatter of boxes and ribbons, each about to reach the next stage of her journey. Invariably the eye traces each figure to the canvas edge, and the mind follows behind it: who are these figures, and where are they headed? What lies beyond what can immediately be seen? This motif of the wandering nude repeats in other works, including Hesperides from Gordy's signature Golden Days Portfolio, 1970, in which similar figures step through a garden in the sky (in this case, cut out as if from a film strip and then stitched back together).

Gordy’s approach is, in many senses, mathematical: his patterns are recursive in nature, spiraling into and out of one another, glimpses of but a single edge of an ever-extending fractal. Yet Gordy frequently returns our attention to the individual figures he depicts, entering into an unusual tension in the process. Despite their rounded, supple figures, and the sometimes lurid attention he pays to sexual organs such as in the brilliant Dog, 1976, Gordy’s figures have been strangely scrubbed of any sensuality whatsoever. The absence of texture, and more importantly, shadow—elements that give rise to imagination, tantalization, and desire—leads us less to the idea of flesh than to surface, a sad, altogether sterile disappointment, the visual equivalent of intercourse with a blow-up doll. One imagines such an encounter would be, in a word, squeaky.

If texture serves as a gateway to sensuality, and sensuality the invitation to feel the body, then Girouard's work offers a powerful contrast. In Gordy's most challenging works, the canvas implies a landscape of endless forms, a proto-erotic arcadia populated by infinitely many armless humanoids or scarlet-tipped hounds. For Girouard, however, the edge of the canvas is less a voyeur’s window than it is a mirror, in which the viewer must confront his or her own political and social identity. She incorporates softer lines and textures, muted colors, the use of stenciled figures, and a private language of symbols and archetypes that over time becomes a form of provocation. Featuring such diverse materials as cloth, rags, strips of wallpaper, beads, sequins, and worked steel, her textures liberate the patterns she explores from the tyranny of the two-dimensional space, and extend those explorations into arenas ungoverned by mathematics or computation. Her work from this era is grounded in political and social awareness, with the subject matter ranging from the AIDS epidemic to space exploration to domesticity and gender roles. Girouard has claimed in an interview that the word “decoration” rarely emerged within the movement itself; the artists of the time thought of themselves as being interested chiefly in patterning. “We were all activists,” she said. “We were just expressing our ideas and our beliefs with whatever materials we could.”

Hence the works on display in the center of the gallery—Conflicting Evidence, 1980—which rework their fabrics into the form of flags. While the large-scale works such as OK, I Hope, 1984; Road Kill, 1984; and Fast Work, 1988, are undoubtedly overwhelming, her smaller, more modest silkscreens, such as Clear, Monument, Fiery Gift, Moon Mother, Tee Pee with Spirits, 1980, offer important insights into the nature of her exploration. In a piece hanging at the entrance to the show, Pictionary, No. 9, 1979, Girouard outlines a private visual language in which she works—a glyph-like code, partly inspired by the code of International Symbols. This language emerged, she has said, in response to the imposition of meaning from outside sources: a resistance to a false sense of nostalgia for “simpler times” that her early viewers and critics frequently assumed, and that she never intended for any of her work. Such a private grammar can usefully control meaning; it can also, however, expand it. For in pieces such as Clear, Monument... Girouard is subtly training the eye to see through the canvas, and thus to see around it: back into those domestic, social, and political contexts, the spaces where injustices, inequalities, and transgressions perpetuate themselves.

Self-imposed constraints have occupied aesthetic movements as diverse as the Martian poets of the 1970s led by Craig Raine, and the Oulipo writers of the 1960s onward. Constraints can challenge writers and artists, readers and viewers to reconsider their notions of artistic engagement. Crossovers between forms, materials, and genres are not uncommon; Ezra Pound's poetry inspired by Chinese pictograms is as much a continuation of a tradition as Xu Bing's contemporary landscape canvases inspired by the same. The opportunities for such engagement are fertile, and like the works in “Patterns and Prototypes,” limitless. Contrary to their label, however, Gordy and Girouard’s works are anything but decorative: they engage the viewer in profound and electrifying ways, they invoke a time period of national uncertainty (the space race had been won, but the arms race remained a standoff), and in their harnessing of this nervous energy they offer important implications for the viewer courageous enough to entertain the notion that the limit of understanding in any domain is the first one worth exploring. This includes our many apprehending selves, themselves infinite in nature: as cognitive beings, as embodied beings, and as political beings. To wit: the thought experiment noted above that recreates that sense of exploration may not be necessary to appreciate the show, but for those who are game to try it, it works best with one's own name.

Robert Gordy, Hesperides from the Golden Days Portfolio (2 of 6), 1970. Screenprint. Courtesy the New Orleans Museum of Art. Museum purchase through the Ella West Freeman Foundation.

Editor's Note

“Patterns and Prototypes” on view through September 25, 2011 at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans.