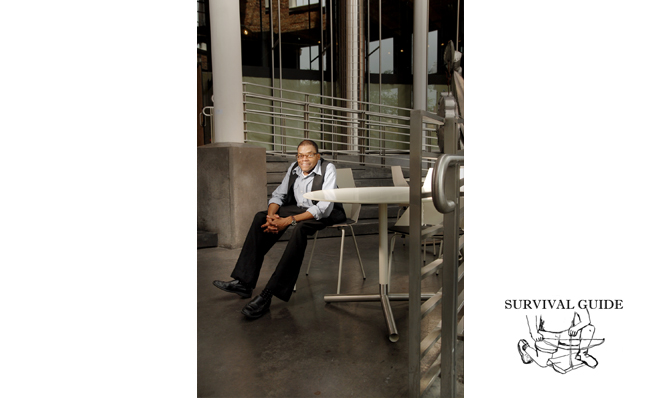

Survival Guide: Keith Duncan

After over a decade in New York, artist and educator Keith Duncan returned to Louisiana in 2007. Aubrey Edwards photographs Duncan inside the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans.

Survival Tip: “Keep healthy and keep painting.”

Editor's Note

After a brief summer hiatus, Pelican Bomb is back! In the second interview in the “Survival Guide” series, Raina Benoit talks with artist and educator Keith Duncan. A native of Plaquemines Parish and consummate storyteller, Duncan draws on contemporary Louisiana history and remembrances of childhood to create his oversized paintings on canvas and fabric.

Raina Benoit: There seems to be a new narrative for visual artists: instead of moving to New York City to be discovered they are migrating to more mid-sized cities—sometimes stopping in New York along the way. You’re originally from the New Orleans area, studied painting at Louisiana State University, and then continued on to pursue an MFA at Hunter College. How did you find yourself in New York and what did you find most influential there?

Keith Duncan: At LSU, Professor Edward Pramuk told me about the Camille Cosby fellowship. That fellowship allowed me to attend the Skowhegan artist residency in Maine in 1990. I met 65 artists that blew me away and really changed my life. I met the artist Gregory Coates, who also received the Cosby fellowship that year and became a good friend. That’s when I decided I wanted to go to New York. Coates introduced me to artists such as Al Loving, Joe Overstreet, Gene Gentry McMahon, and James Little—all masters of abstraction. I liked the fact that they were struggling artists doing their thing. They taught me the importance of knowing one’s craft. Some of these artists have gotten their dues. Some of them never have, but they were part of a movement then and many are still painting. It’s important to know the academic side of things—the history of art and art theory—but at the same time, I really learned from seeing these artists in their studios.

RB: Your active exhibition record has gained your artwork steady attention. Things seem to have especially taken off for you since settling back in New Orleans in 2007. Last year alone, you had two solo shows: one at the CUE Art Foundation in New York curated by Willie Birch and then shortly after at the Healing Center as part of Prospect.2 where you sold every painting. How has it been for you up until now in regards to showing your work and selling it?

KD: The success at the Healing Center is the reason that I have a studio now! It went well when I showed the work in New York, but I believe New Orleans viewers connected more with the Southern themes and symbols—local landmarks such as the cemeteries and the Crescent City Connection bridge.

Before the move, I had maybe three or four solo shows in New York but it was mainly group shows. I found myself getting lost in the group shows. Not that they’re a bad thing. I like showing with other artists, but then it became redundant. Come Black History Month I’d always know that I could exhibit; or a politically themed group exhibition, I knew I could get into that. But there’s nothing like seeing an artist’s work all together like in a solo show. Actually, the last two or three years in New York I ended up showing many paintings at friends’ apartments. I thought I was being overlooked in New York. Now that I’m back home, I feel like I’m getting some traction.

RB: You spent 15 years living and working in New York. How does making a life here in New Orleans compare?

KD: It feels a little better (laughs). Having family close is important and having their support. The rat race in New York was wearing me out; rent was always being raised. Many of my friends were moving out of the city. It was a good time to get out. I just had to say, “Why keep struggling like this?” I may have some of that here in New Orleans, but I do feel more relaxed. There is a higher quality of life here. In New York it was always feast or famine.

RB: How has your work changed since you returned to Louisiana?

KD: I went to Delgado for two years, then I transferred to LSU, and then I went to New York. I never got to discover New Orleans. I was just doing the school thing. Coming back now, I’m excited to be a part of the whole art revitalization that’s going on in the Bywater area. It reminds me of Williamsburg and the Dumbo area of Brooklyn, which really exploded with artists and art spaces in the 1990s.

As for the work, my paintings are always about my environment. Now that I’m back home, I’ve started incorporating fabric into my work. Fabric has ties to Southern traditions like quilt making, storytelling, and folklore. I’ve been listening to my father; he’s at a stage in life where he’s telling a lot of stories about his childhood, my childhood, and Plaquemines Parish. Growing up, my uncle would say things like, “the Devil is beating his wife,” when the sun was out and it’s raining. That’s the kind of folklore I’d like to explore more.

RB: I appreciate your work’s balance between concrete symbols and poetic description of daily life. I’m thinking of your Ghetto Angels series in particular, where black men from your neighborhood at the time in Harlem were painted with angels’ wings. You allow the content to be complex without being didactic or overly romanticized. How do you approach the categorization of being a “black Southern artist?” Do you find these categories liberating or limiting within the larger contemporary art context?

KD: I’ve always thought that artists should be the recorders of the times they live in and I think I’ve done that, for example my painting of the BP Gulf oil spill. I’m interested in social and current events, just like a reporter. The fact that I’m an African American is going to transfer into the work. I want to talk about what’s going on in my community but at the same time connect with universal issues.

RB: You’ve described your artwork as being “outsider art,” influenced more by music, dance, literature, and pop culture rather than drawing from merely visual art sources. I’m curious as to how you reconcile this approach to your work with your many years of art education?

KD: They say it takes 10 years to shed the academic dogma and it’s true. For my MFA thesis show, I wasn’t even painting. I was drawing the outline of the body, disabled figures with text about the Americans with Disabilities Act. My work was only focusing on disability. Most of my close friends would say, “You’re not disabled; you’re just shaped different.” Regardless of how I characterized myself, I had to step back to see what I really wanted to talk about. It took getting out of school, meeting other artists, seeing how they worked, and becoming disciplined in my own practice. I look at many of these young up-and-coming artists and I want to tell them that it’s not about being a trend for the moment. You don’t want to be a big star now only later to be forgotten. I have to say, “What’s wrong with a little struggle?”

Keith Duncan, I Got My 'Mo'Jo' Back, 2010. Acrylic on fabric on canvas. Courtesy the artist.