Reflections: Roy Ferdinand

It’s getting hot! Already longing for cooler temperatures, curator and artist Amanda Brinkman reflects on buying her first work of art—a drawing by Roy Ferdinand and a holiday gift to herself.

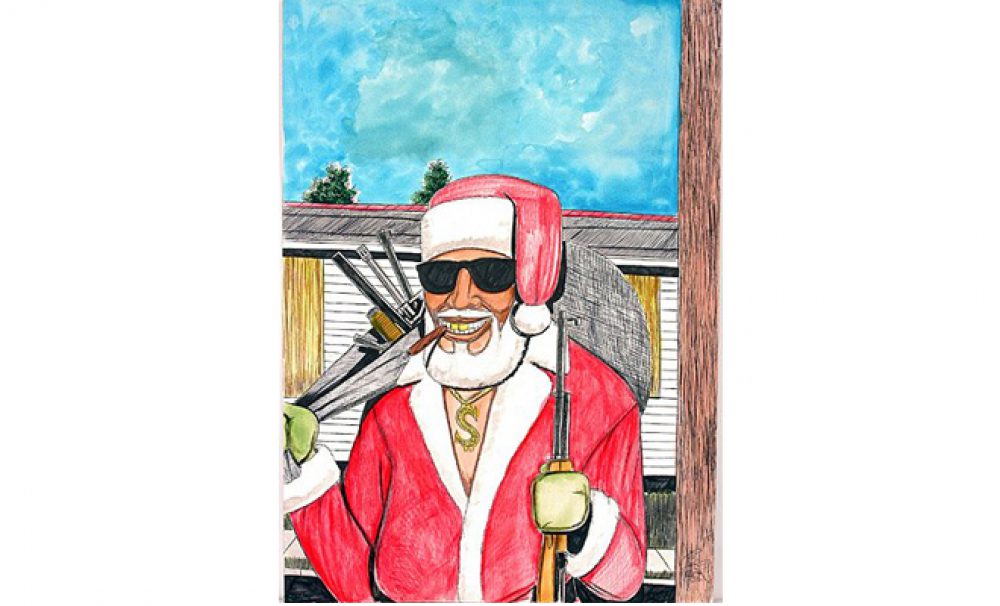

The Gangsta Santa was bought by the author on eBay, but a similar piece was offered by Slotin Folk Art on liveauctioneers.com.

After college, I managed the San Diego branch of the International House of Blues Foundation. People go to the House of Blues for the music but fewer know about the Foundation’s educational mission—teaching kids about blues and visual art traditions in the South. Part of my job was to develop docent-led tours of the Foundation’s self-taught art collection for school groups ranging from third to twelfth graders. While I tried to vary the content, much of the tour ended up focusing on the visual culture of New Orleans. While Chuckie Williams’ paintings of Mardi Gras Indians and Roland Knox’s works created entirely of beads proved accessible enough for most students, Roy Ferdinand’s drawings always presented more of a challenge. The younger students especially were transfixed by the casual, even cartoonish, violence in Ferdinand’s drawings, but unpacking its politics was completely outside the scope of their understanding. With only three or four minutes of discussion for each artwork, looking at Ferdinand’s drawings became an overwhelming task and was eventually eliminated from the tour altogether.

When I later moved to Chicago for graduate school, I stayed involved with the Foundation, doing occasional tours and volunteering at their local outpost. One Saturday, I signed on for an art-making workshop with a group of at-risk boys. They were clearly uninterested in the bead-collage project at hand, so I gave them an impromptu tour instead. The boys gravitated towards one of Ferdinand’s drawings of a man holding a gun leaning against a lamppost, which we talked about for the majority of their afternoon. They were comfortable in front of the work, the grittiness of the drawing directly speaking to us all after one of Chicago’s most violent summers. They found it funny and saw an opportunity to test how much they could cuss in front of me, gleefully using every expletive to describe the drawing. Letting them direct the conversation enabled me to better understand the way Ferdinand’s drawings operate. The violence depicted was comical, yet very real, and no pre-planned tour could have considered the degree to which this particular group of boys would simply be able to relate in the moment.

I relocated to New Orleans two years later. Holiday shopping for my friends and family that winter, I was searching for the perfect one-of-a-kind item for each person, which is how I stumbled upon an under-priced Ferdinand drawing being sold by a collector in Atlanta on eBay. I was broke and the thought of spending any money on myself seemed absurd. Still I knew I had to get it. I originally planned to give it as a gift, but when it arrived a few days later I was too excited to actually part with it. It was the first piece of art I ever bought and I was surprisingly pleased to find that it came in a cheap plastic poster frame, the opposite of the overly ornate frame I had expected.

Ferdinand’s work had presented me over the years with problems of representation and didactics—namely how to articulate its complicated nuances to children—and there I was like a child on Christmas morning. Appropriately timed, my holiday present to myself was one of Ferdinand’s Gangsta Santa drawings, which now sits prominently in my kitchen in a crappy plastic frame, as approachable as ever in the most visited room in my house.