Artists in Conversation: Paul Dean and Kyle Bravo

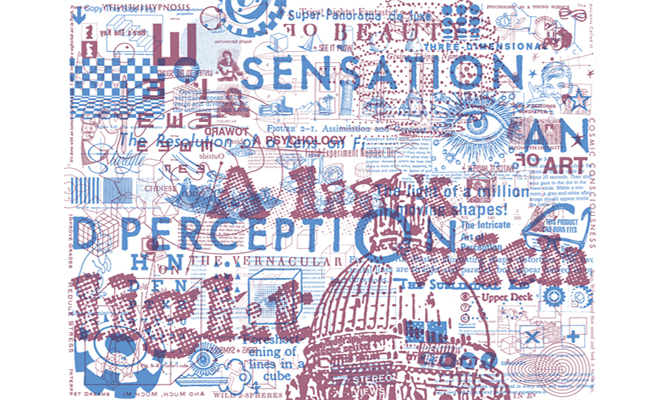

Paul Dean, A Link With Light, 2006. Digital laser print. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

For the first in a series of “Artists in Conversation,” Paul Dean talks with Kyle Bravo. An associate professor at Louisiana State University, Paul Dean teaches typography, color theory, and graphic design history. His work is currently on view at the Baton Rouge Gallery, where he has been a regularly exhibiting member for over 15 years. Best known as a collage artist, Dean has most recently adopted the role of DJ “guide,” connecting listeners to a selection of internet radio streams across the country at www.djmisc.com.

Kyle Bravo, along with his wife, artist Jenny LeBlanc, founded the printmaking studio Hot Iron Press in 2002. He currently teaches visual art in New Orleans and is a founding member of the artist-run exhibition space, The Front. He studied under Dean from 1996 to 2000 as an undergraduate at LSU.

Kyle Bravo: Thinking back to my formative years in art, you and Sean Starwars were probably the most influential. You both were making things I was excited by, helping me form my ideas about what was interesting. I’m curious—because you were my teacher, and now I also teach—what you think about the relationship of teaching to your creative activities.

Paul Dean: Well, I teach a basic type class for sophomores first semester and then color theory the next semester for the same students. Because I emphasize type so much, I keep that element in the color class. Type isn’t really my art, though I have been making these little books lately. I collect quotes about color out of magazines and put them together to make a book on green, a book on red. I sequence the quotes, so that there’s a connection, and you really learn something about what a color means. Those are thrilling, but they’re not really art. They’re like my graphic design project...or maybe more than that, it’s a research project.

I was printing them out at school and giving them away to my students, but I kept running out of books! It became obvious that I had to take the project online, so a friend is helping me make an app for the color quotes. I’ve also been collecting quotes about type and letter forms from unusual sources and that might make a different app eventually—an app of quotes about type and typography. Maybe I’ll even design a book or print a publication that really does something interesting with each quote.

KB: So, you think of yourself more as a designer, not necessarily as an artist, right?

PD: In school, yes, I think what I teach is graphic design rather than fine art. The last show I did in an art gallery though was called “The Shirt Off My Back,” and it was Hawaiian shirts stretched on square frames—sometimes with the pockets, sometimes with the buttons up there. It was definitely to my taste. I already had a lot of shirts, but I went to thrift stores and looked for more. I usually wore them at least once, if not a lot longer, before I put them on the frames. So it was conceptual art, but it’s simple. I’m just putting this shirt on the frame. I guess I’m troubled by the fact that it’s so easy to do, on the one hand. On the other hand, it’s completely sincere. These are shirts that kept me warm. You know: cloth. I still love them.

KB: You understand that the final works are beautiful, but all you did was stretch a shirt. So you’re like, “Is that art?,” which is such a difficult question to answer, especially when you’re addressing students who are still learning to see and think about art’s parameters.

PD: I heard some people saw the show and thought, “This is ridiculous! It’s not a painting.”

KB: I kind of dig that reaction when it comes to my own stuff. I’m really interested in that minimal aspect of what you do—that less is more sort of thing—using the smallest gesture to make an impact. I’m now doing these rinky-dink drawings, and there’s always that insecurity factor. Is this meaningful? Is this enough? Is this just because I can’t paint?

PD: I was having lunch with a curator in Baton Rouge, and she saw no difference between these shirt pieces and paintings. I thought, “Ka-ching! I found it. Someone appreciates it,” because I feel that insecurity. I’ve been trying to paint, and it’s hard for me. I guess because my imagination always takes it further than my painting technique can.

KB: But so much of your work, at least the stuff I know, is about taking things that are already there. Not necessarily creating something totally new, which I don’t necessarily even believe exists, but you’re taking found imagery, then compiling it or collecting it and reworking it somehow. It seems like that’s a huge part of what you do.

PD: It is but I want it to mean something or to be worth looking at rather than feeling just tossed together. It’s kind of insulting: the conceptual art that looks and feels shallow. If it’s going to look simple, there just has to be some meaning or thought behind it...sincerity, there has to be some sincerity behind it.

KB: I’ve come to decide that what really matters is whether I like the work. Do I like this drawing of a beer can or this stupid little squiggle? I think that if I’m genuinely responding to it, then surely there must be other people out there who will also respond to the image.

You have a history of making artists’ books as physical objects, but it seems as if you’re increasingly getting involved in digital media, like the apps and your website: djmisc.com.

PD: It’s so hard to redesign and republish a book and then run out of the edition again. With an app, I can just update it. It seems the more logical way to go now, but I still prefer books. In the future they’ll be the luxury items: books and records. I remember hearing a student say, “You know, I really like holding a CD.” I couldn’t help thinking, “You should try an LP. Man, it’ll blow your mind!” When you bought a record in the 1970s, you went home and you looked at the album cover for 20 minutes...each side! So really, it was a design and art experience too.

KB: Whereas now, when you download an mp3, you get this one-inch digital icon.

PD: And when you get a job designing an album cover, you’re expected to design the little iTunes thing. You have to take out type that doesn’t work at a smaller scale. It’s a shame really because I think we may be losing a generation of graphic designers. I bought records for the music, but that’s how I got into graphic design. Punk rock changed me. The Sex Pistols’ first album cover, it was like, “Oh my god! This is just ink on paper!” It was a revelation, there were no secrets there.

KB: That seems to get back to what you were saying earlier about the beauty of really simple, honest gestures. It doesn’t have to be this overwrought thing. You can just cut some stuff out and slap it together and it can be amazing.

PD: Especially if it affects somebody, if it makes them think in a new way...

KB: Your website seems to be devoted heavily to music. I know you used to be a DJ. Do you still do that?

PD: My turntables got stolen. My house got broken into. It was terrible and traumatic. Amazingly of course, they stole the turntables and the microphone, but they left all the art, all the musical instruments, all the records. They left everything unique. I guess my interests aren’t very hot on the pawnshop circuit or something. When this happened though I also realized that making music—writing songs and recording them—was something I’d been avoiding.

KB: Thinking of you as a DJ really makes a lot of sense. It’s the musical equivalent of collage.You’re taking this found source that already exists and then...

PD: It’s audio collage, which is probably why I was excited by it for so long. Lately I’ve been recording music with Jeremy Grassman. His parents were both musicians in Baton Rouge. I’ve seen a picture of his mother from this all-girl rock band in the ’60s with matching outfits. He moved back here from Dallas. He and his girlfriend live in a trailer next to a small house they’ve turned into a recording studio. They have a four-track there, which is the way I’ve been recording since high school. I’ve never really learned another way.

For a while, I was really into collage. I was finding things and I was layering them and I didn’t care if I looked schizophrenic, or you know, paranoid. I made that book. Oh, you’ve got that book! [Bravo holds up the book.] A.R.: Manifesto! Now, when I look at it, it’s just scary. It looks like a paranoid rambling to me.

KB: I mean, it is, sort of...

PD: I know! I also did a series of pieces called Sleepers Awake that were these crazy collages. I heard this terrible story that after the opening where I showed those somebody went home and killed himself—someone who knew one of the other artists. Now I worry that my work is just making people crazy.

KB: But that’s not because of your work!

PD: I recognize that on one level, but I can’t help but think about that guy and wonder what he was looking at. That series is so end-of-the-world...

KB: Don’t you think there is an important role in making the stuff because otherwise wouldn’t it still be inside of you? It’s a way of processing it.

PD: I guess I’ve started thinking more of the audience and less about me. How does this affect people? How does this affect the world?

KB: What about the Sex Pistols’ album you were describing? That view of the world is dark!

PD: I worry about what punk rock has done to me and the world! I mean, I was 18 laughing at death and madness. That’s part of why I like my new work so much. “The Shirt Off My Back,” those pieces are peaceful; they’re calm. They’re square, so they suggest a larger area of a fantasy paradise or something, but there’s no way it’s going to hurt anyone looking at those. For a long while, I was trying to get people to wake up and pay attention to how bad things are going to be. And now that they’re here, now that things are bad, I’m just kind of like, “well....”

KB: The last time we sat down and talked was around the time of Sleepers Awake and you seemed really riled up. Maybe that was around Gulf War time? It strikes me as interesting because recently my wife told me she thinks these little books I’m making to send out to galleries to drum up shows make me look like a crazy person. She says I curse too much, everything is so negative, I write in this serial killer scrawl. And it’s weird because I guess I see that but I never really thought about it that way.

PD: Yeah, maybe it’s time for some happy art.

KB: This is the therapy though! I think if I wasn’t doing this, I’d just be angry all the time. It’s a way of processing it, but maybe I should try my hand at just stretching some of my shirts.

Another thing I think about with you is you had us make sketchbooks as a project in school.

PD: Yeah, research notebooks.

KB: That was a pretty important thing for me. I really enjoyed doing it, searching for all this stuff I found interesting and inspiring and then compiling it into the book and collecting it. That made me start to think about the book as an art form. When it was done, the book would almost be a work in and of itself, a finished piece, even though it was just the initial stages of the research. It made me think about how an initial gesture could be the end product too. Do you still teach that?

PD: I still do the notebook, and I get a lot of good responses, too. You know, I forget about it but former students say, “Paul, I still have the notebook.”

KB: I actually had like 10 of them, because I kept doing it after school. But they all flooded in the storm, they were all mildewy and destroyed so I had to throw them out.

PD: I think it appeals to so many of my students because it’s a way of working even when you don’t know what you’re doing. You can just sit down with your notebook and pen. If you feel like doodling, you doodle. If you have something to glue in, you glue that in. And you don’t put too much pressure on yourself. You just react.

And then at the end of the semester, I ask the students to show their notebooks to each other. I remember back in the early days people used to staple some pages together that they didn’t want other people to see. I love that—their secret, private things.

KB: Another really big influence for me from school was your movie list. Once a semester or once a year, you’d give us this updated “Paul’s list of the top 50 movies we should see.”

PD: Have you seen them? Did you watch them all?

KB: I’m still in the process. You may remember, I wrote you a year ago for your updates. I put them all in my Netflix queue, and I’ve been working my way through it.

I found your list interesting because I really liked the idea of the list. But then watching your movies, some of them I totally hated.

PD: They were probably on there for some secret reason. I was trying to warp your life!

But honestly, I love watching movies. That’s the modern equivalent of painting to me. I made an animation in 2007 with Wei He who taught at LSU. It is called An Abecedary. It’s an animation of the alphabet based on a book of type history.

KB: Why do you think that you’re so attracted to typography?

PD: When it’s been carefully controlled by someone who knows what can be done with type, the history of type, it can be so beautiful! But it’s usually so bad! You know that, of course. You live in Louisiana; 95% of any signs that you’re going to see are crap. So once you have the eye for good type, it’s just disappointing looking at the world. It’s kind of a curse in that regard. And maybe that’s why people who get into type go so completely into it. All they want to do is look at their books and design their own projects because everything else is so ugly.

Paul Dean, An Angry Butterfly, 2010. Stretched aloha shirt. Courtesy the artist.