Artists in Conversation: Jessica Bizer and Fred Tomaselli

Fred Tomaselli, Echo, Wow and Flutter, 2000. Leaves, pills, photocollage, acrylic, resin on wood panel. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York.

Editor's Note

For the second in a series of “Artists in Conversation,” Jessica Bizer talks with Fred Tomaselli. Jessica Bizer is a painter and mixed-media installation artist carrying the torch for abstract painting in New Orleans. She is a founding member of the Good Children Gallery, a collective and artist-run exhibition space in the Bywater. Her latest solo exhibition, "After Forever," opens this weekend, Saturday, April 14 at Good Children.

Emerging in the 1980s as part of the Southern Californian punk-rock and performance-art scenes, Fred Tomaselli is best known for his dazzling painted collages made from pills and marijuana leaves. He currently lives in New York and met Bizer for the first time in New Orleans when exhibiting during Prospect.1 in 2008.

Jessica Bizer: Last September you made your first trip to China for a show at James Cohan Gallery’s Shanghai outpost. What were your impressions? I've never been to China, but I imagine it to be completely overwhelming and fast-paced, at least in the cities.

Fred Tomaselli: I only visited Shanghai and Beijing. Both cities are frenetic, hyper-capitalist boomtowns. The rapid build up of infrastructure, skyscrapers, congestion, smog, and new wealth were utterly disorienting. On the flip side, the Great Wall, Beijing's Lama Temple, and Shanghai's new aquarium were utterly sublime.

JB: You’ve often talked about the artificial quality of the Los Angeles landscape and how it has influenced your work. Given the "boomtown" qualities of Shanghai and Beijing, did you experience any parallels between Southern California and urban China? I'm curious if the flashier consumerist side of China felt familiar.

FT: Apparently the Disney corporation is building a new theme park in Shanghai, which ought to be a perfect match of sensibilities. Both Disneyland and China foster authoritarian, panopticon environments for the supposed "good" of the consumer. Both erect "happiness" facades that simultaneously deny the existence of shit while glorifying the corporate.

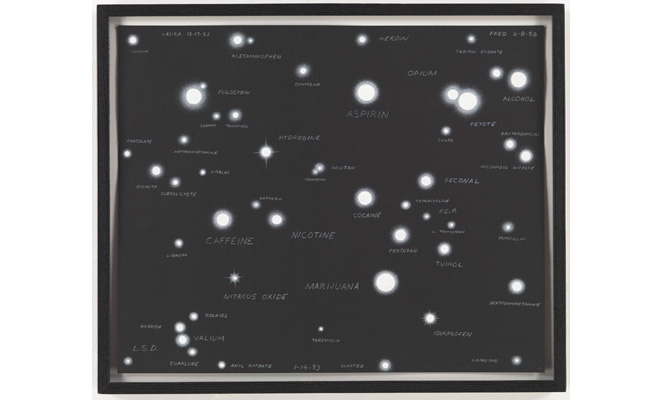

Fred Tomaselli, Celestial Portrait of Fred and Laura, 1993. Gouache on paper. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York.

JB: The work you had in the Shanghai show, especially the Bloom series, had a much more painterly and "zoomed in" quality than your usual paintings. In many ways, the Bloom paintings feel like a close-up of the intricate collages that traditionally comprise your work. What brought about this shift?

FT: The Bloom series is a continuation of photogram-based work that I've been doing off and on since 1990. The first photograms were Chemical Celestial Portraits that originated out of questionnaires asking individuals to list their birth dates and drug histories. The birth date would correspond to an astrological sign, which in turn would correspond to an astronomical constellation. I would then make a starry, nighttime image of these constellations by placing pills and sugar on photo paper, exposing it to light, and then developing it in a standard three-step photo development process. Afterward, I'd use white pencils to re-label the "stars" with the drug history of the sitter, thereby creating a portrait that takes in inner space and outer space.

The Chemical Celestial Portraits used conceptual strategies to find form, but my Bloom series had almost no conceptual forethought. When I started this series, I had absolutely no idea what I was moving toward. I began by placing leaves from my garden onto photo paper to see what would happen. After I developed the images, I found that white shapes had revealed themselves wherever the leaves overlapped. I decided to start painting within these white shapes and started seeing these painted areas as flowers blooming out of the images of gray-scale leaves. I liked how the real, the abstract, the photographic, and the painterly all sort of held together in these works. It's not unlike the tension between realities that can be found in my other paintings, but I think they look really different from them.

I like your comment about the "zoomed in" quality of the pictures, since they have a one-to-one scale relationship between the real leaves and the shadows that they leave on the photo paper. I also like not knowing exactly what it is that I'm doing. Mucking around in the dark is way more exciting (and unnerving) than executing work that you can already anticipate.

Fred Tomaselli, Bloom #2, 2011. Gouache on photogram. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York.

JB: Given the often-burdensome context of painting, how did it feel to work in a more painterly manner? When I'm dealing with the painterly qualities of my own work, or even others' work, I automatically encounter a host of art-historical and conceptual problems. It's almost impossible for me to make a purely formal decision. That experience can be completely fascinating or totally annoying, but it definitely keeps things from getting boring.

FT: In the beginning, I had to think my way out of history in order to make art, but once I got started, the work began to take on a life of its own. If there's a big difference between my early and late work, it's that I'm now way more driven by evanescent impulses. There's always some painterly process or another that keeps me off balance, and there's always some technical problem to puzzle through … sometimes they're the same thing.

JB: When you’re engaged in that process, how do you deal with irony? For instance, at one time I could only appreciate Abstract Expressionism on a kitsch level. Those paintings seemed so ridiculous and bombastic to me. While I sincerely appreciate the style now, I can't shake the ironic attraction I once felt towards the work. That conflict is a frequent part of the viewing experience for me. As you’ve worked your way through art history, and pop culture as well, what has been your relationship to irony?

FT: It sounds similar to yours. First off, when it comes to culture, maybe we should look at irony as a preexisting condition that we have to learn how to manage. Maybe I have to pass through an ironic state to get to something heartfelt and honest—something real. Just because I pass through this state doesn't mean I have to live there, and I don't think it necessarily diminishes a "primary" experience. Besides, I don't have another state to compare it to since I don't really remember processing culture differently. To me, this multiplicity of experience is as real as it gets, and I try to put that into my work. By the way, there's nothing more boring than irony for its own sake. And I don't have ironic experiences with people … I just have them with certain things made by people.

Jessica Bizer, It's Really Going to Happen, 2011. Acrylic and airbrush on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

JB: You've often mentioned Romanticism’s influence on your work. I'm particularly interested in the link between a psychedelic sensibility and Romantic concepts. These styles have so much in common—an interest in vast and uncontrollable space, a focus on simultaneously appealing and threatening sensations, among other things. How do these styles overlap for you?

FT: A Romantic would define the sublime simply as an overwhelming experience generated by forces bigger than him, which can be both beautiful and terrifying. Sounds like acid to me! While my generation of stoners was pretty suspicious of the term, I couldn't deny my post-punk psychedelic experiences. As a matter of fact, probably the only time I ever truly experienced the sublime was when I was tripping my brains out!

JB: What about the connection between the sublime and the digital world? As I see it, using a computer is a completely magical experience. The screen immerses the user in an infinite, luminescent environment in which process is made invisible. The seamless and glowing qualities of your paintings seem to echo this space.

FT: Computer screens seem to have a sympathetic relationship to my pictures even though I was onto my trip way before they were ubiquitous. It's funny, but I think the huge variety of mental and physical transportation technologies that were developed in California (theme parks, the movie industry, the music scene, the aerospace industry, car and surf culture, and of course, the popularization of mind-expanding drugs) all provided the perfect environment for both the sensibility behind my work and the development of the personal computer. I think it was Mickey Hart from the Grateful Dead who once said that the band wasn't in the music business; they were in the transportation business. You could say the same thing about so many Californians from Tim Leary to Steve Jobs to myself. We're all in the transportation business.

JB: How then did your move from California to New York affect your work?

FT: L.A.'s aerospace industry provided a lot of electronic surplus that ended up in my immersive installations. New York had very little electronic surplus to begin with, and as the few remaining surplus places on Canal Street closed, my work got less technological. Plus, I was looking at a lot more pictures in New York. The questions they raised led me toward making discrete objects that got progressively flatter and flatter. Five years after moving here, I was making resin pictures filled with psychoactive materials. I never expected that to happen!

JB: What ideas link your earlier installations with your current work?

FT: Reality dislocation.

JB: Speaking of which, what was your first really dramatic art experience?

FT: When I was a know-nothing teenager, some friends and I happened to walk into a James Turrell show at a gallery. There appeared to be a black rectangle painted on the wall of the dimly lit space, and my friends and I started laughing at it. "Stupid modern art," I thought as I reached out to maliciously touch it. To my surprise, my hand passed through the wall and into a limitless void. My laughter immediately disappeared into awestruck silence. Turrell taught me that what you see isn't always what you get.

Around the same time, I happened to see Bruce Nauman's retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Again, I had no context for it, but being an alienated kid, I really connected to its pathology, paranoia, and dark humor. I saw it as a Disneyland of the repressed.

JB: Ending on a personal note, I recently had a baby. I'm curious how having a child affected the way you work. How did you manage practical issues such as your daily studio practice? And did the change cause any perceptual shifts regarding art?

FT: Having a child forced me to keep more regular hours. I try to use those hours more efficiently, but I'm still a slowpoke, and I still make tons of mistakes and left turns. While being a parent can aid in the ossifying effects of adulthood, the opposite can also happen. Having a kid can help you access your “inner kid" and sometimes that can be liberating. Kids get you outside of yourself, which isn't always bad, especially for an artist. It's also fascinating to note how all the aspects of adults are hardwired from birth. Kids are greedy, selfish, cruel, and sometimes violent, but they can also be so damn interesting.

Jessica Bizer, Atrium Expansion, 2011. Acrylic and airbrush on canvas. Courtesy the artist.