Whiz, Bang, Thud: Bob Tannen’s Balls

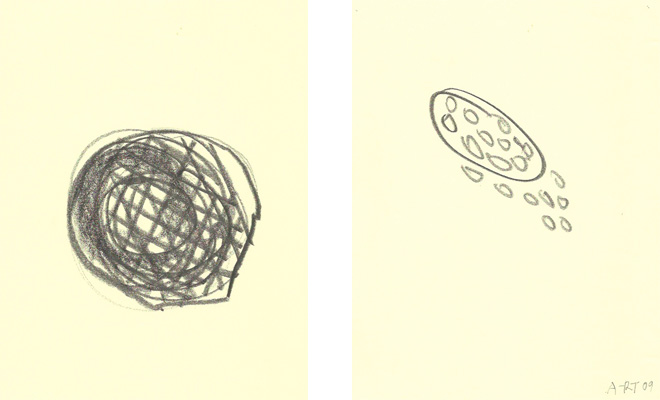

Bob Tannen, baseball and golf ball from the Balls series, 2008-2009. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist.

The calendar has flipped to July and planet Earth still plods along, functioning and dysfunctioning as it did long before May 21, when Harold Camping found himself “flabbergasted” that his apocalypse prediction didn’t manifest. Things would be so easy if we could trust our prophets and visionaries, but history shows that very few of us do; the crop-circle farmers and Harold Campings of the world invite such derision that to be a true believer is to waltz with ridicule. This has been going on for centuries. Galileo’s (correct!) hypothesis that the universe revolved around the sun earned him a lifetime of censorship and house arrest in Italy.

That thin line between the shards of madness and the precision of truth anchors Bob Tannen’s drawings of balls. Having lived in New Orleans since the 1960s, Tannen is among the first conceptual artists to make his primary residence in the city. His work has encompassed twisted hunks of hanging aluminum and sagging inner tubes affixed to barn doors. He has designed prefab housing units for post-Katrina New Orleans, devised obscure classification systems for rocks and boulders, and come up with many more examples of madcap pragmatism. To summarize Tannen’s art to the uninitiated: Rauschenberg’s sense of the poetry of objects sandwiched between Buckminster Fuller’s refusal of impossibility and Robert Smithson’s ambition to organize that which defies systemic thinking.

Tannen began drawing balls in 2008 after seeing Chris Sullivan’s art. Following the storm, Sullivan collected basketballs that had been swept away in the water. Found in various stages of deformity—some were deflated, some mangled, some tattooed with mildew—each had a personality that divorced it from its assembly-line origins. When Sullivan showed these at KK Projects in 2008, Tannen chipped in with dozens of drawings of basketballs; in 2009 he mounted an exhibition at the former Studio 527 space of several hundred drawings of various types of balls. Each of the 600 or so graphite drawings completed in those two years is made on a modest 11x11” sheet of paper. Superficially, the balls take their cues from sports. There are basketballs, baseballs (Tannen calls them “hardballs”), softballs, footballs, golf balls, tennis balls, bowling balls, soccer balls, and, somewhat anomalously, shuttlecocks. They are housed in PVC sleeves within several overstuffed binders, the kind in which collectors of coins or baseball cards hoard their wares.

Tannen’s balls have the same starkness as the Philip Guston drawings that preceded his return to figuration in the late ’60s after two decades of abstract painting. There is no background or context, no color, nothing but the subject in isolation. Sometimes they are hard-edged like Fuller’s geodesic domes; sometimes they are round and robust like a Ken Price egg. Occasionally, some shading gives the rendered object a glimmer of perspectival “realism,” but Tannen’s balls mostly exist in a state of flat iconicity. The obvious question: why make 600 variations on these simple objects used for games? To Tannen, a ball is not only an accessory to a game, but a sphere deeply rooted in the mythology of flying objects and the functional ingenuity of roundness. A baseball gripped along the seams and thrown with a violent pronation of the wrist breaks both vertically and horizontally. As a batter, being subject to this for the first time is like being the butt of cruel occult wizardry, a humiliating practical joke. A football—the most awkward ball to handle—artfully cuts through the air in an elegant spiral when tossed properly. Improperly, it will wobble to a pathetic crash landing like a flying bird that has taken a hunter’s bullet, hence the vernacular for poorly-thrown pigskin: duck.

Not all balls of the same type are alike. They evolve. They develop dissimilarities, as evinced by Sullivan’s basketballs. Sometimes their anomalies are short-lived and hilarious. Any ball, when struck with sufficient force, becomes distorted. Bearing witness to this can be both ridiculous and tragic. A pitched tennis ball, when fouled off just so with a baseball bat, is sent aloft with so much backspin that its shape morphs from a true sphere to a ludicrous, donut-like oval. It plops to the ground, bounces spastically away, and has magically re-assumed its original form by the time it’s retrieved. Then there is the humorless bummer of the dematerialized ball: a baseball divested of its cowhide is an unusable mess of brownish yarn and cork guts. There is no more obvious reminder that balls are spheres of trauma, objects made to be the recipient of legal and celebrated assault.

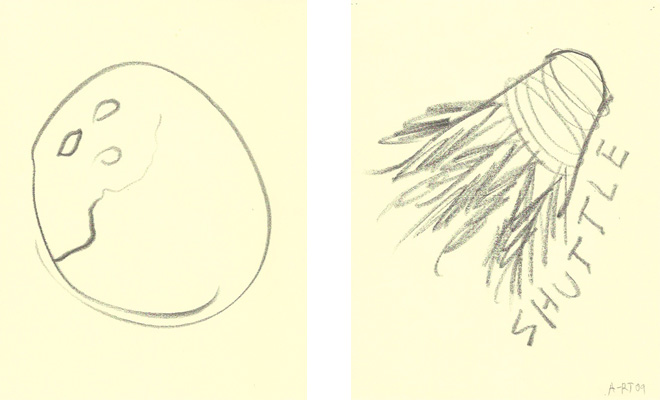

Many of Tannen’s balls are rendered with distortion in mind. In his binders, each family of balls is grouped; the progression tends to be from most to least literal. A 75-100-drawing arc with a deceptive beginning of relative literalness terminates in Futurist/Cubist fracture. Over the course of several drawings, a golf ball progresses from full to crescent moon. Some golf ball drawings could be stoned renderings of mitosis followed by pregnancy: orbs conjoining and then housing more orbs within them. Several drawings are inescapably funny. A basketball loses its stripes like a tiger. A soccer ball sheds its last geometric patch, becoming a naked blank of a ball. A Tannen shuttlecock has the advantage of wordplay—it is both cock and balls—and he emphasizes the sexuality of this inevitably phallic object. The bowling balls—Tannen’s fullest—are probably also his funniest because of how the finger holes approximate a caricatured face. Taken together, the drawings become an experiment of gradually severing balls’ inseparable relationship to the quasi-religious global function of sports. These aren’t balls, exactly; they’re the ideas of them.

There is a wonderful Werner Herzog documentary film titled The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (1974). The eponymous Steiner is the world’s top ski jumper, or as they beautifully said in the ’70s, “ski flyer.” Because of his perfect technique, Steiner soared so far off the ramp that he would land near flat ground, endangering life and limb. Eventually, Steiner began his descent from further down the ramp than his competition, intentionally generating less velocity prior to his jump. He still won easily. In one of Herzog’s mesmerizing slow-motion shots, it is obvious why Steiner was the best. His neck cranes forward toward the tips of his gargantuan skis, his arms are tucked in neatly at his sides, all is still and compact. This is a human mimicking a perfectly-thrown football. But then something—wind, nerves—makes Steiner twitch a little, and suddenly everything goes awry. His skis catch the air instead of slicing through it and he is doomed. He flails helplessly, inexorably earthward—a duck.

Tannen wrote his own mini-manifesto for the balls, but the Herzog scene could be its ancillary. Sports—the flying Steiner, a spiraling football, a knuckleball flicked with no rotation so that it is subject to nothing but wind and gravity—can really emblematize an awesome aesthetic ideal. But just as Steiner crashes to the ground, Tiger Woods slices a drive or Drew Brees throws a duck. The perfection of games is only beautiful because it is fleeting. Mexico was home to some of the earliest ballgames in recorded history, when the losing team was said to be killed. The individual histories of sports, spheres, and flight are stories of ambition and hubris. Tannen’s balls are their abstract archive. To flip through them and experience their physical disintegration across many pages is to witness the allegory of the flying object: one of madness and truth. Balls, like heroes, will come down. Nothing flies forever.

Bob Tannen, bowling ball and shuttlecock from the Balls series, 2008-2009. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist.