The Artistry of Loujon Press: Triumphs and Shortcomings

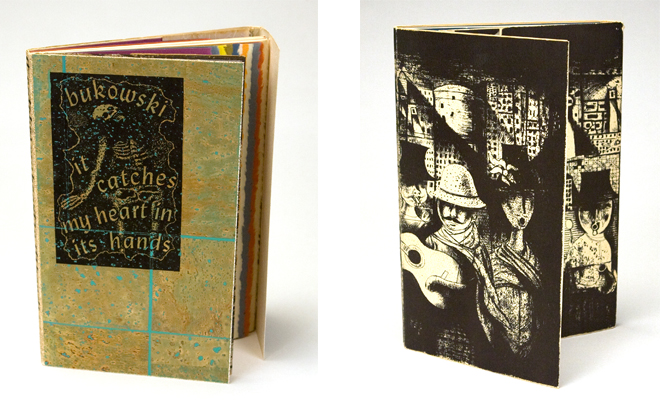

Loujon published two of Charles Bukowski’s earliest books, It Catches My Heart in its Hands (1963) and Crucifix in a Deathhand (1965). Photos by Akasha Rabut. Courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection.

“How does one talk about a Loujon creation? I could roll cigarettes and drink beer all night and write about it and end up with all the pages, and perhaps myself, on the floor and still not have said it.” — Charles Bukowski, in a letter to Loujon publisher Jon Webb

Editor's Note

In this two-part series, Room 220 editor Nathan C. Martin examines the successes and failures of Loujon Press, a fine-press publisher based in New Orleans in the 1960s, in terms of the aesthetics of artistic bookmaking.

The short-lived but mighty Loujon Press has become a legend among New Orleans literary circles. Admired for its publication of prominent writers at the tail end of the Beat Generation and exalted as a model of DIY ethos for the Sisyphean feats of its rag-tag progenitors, Loujon has been the subject of a book and a film documentary, it was the dedicatee of the first New Orleans Book Fair, and its books and journals remain coveted treasures for archivists and collectors throughout the region.

As much as Loujon was esteemed in its day for the words on its pages, readers from the 1960s were often as struck by the craftsmanship and artistry of the publications. Husband-and-wife publishers Jon and Louise “Gypsy Lou” Webb were equally concerned with editorial content and the aesthetic makeup of the objects they created. Contemporary literati who are aware of Loujon’s books and its The Outsider magazine but who have neglected to visit an archive and hold the printed pieces in their hands are woefully unaware of the complete Loujon experience. It is one thing to read Jeff Weddle’s outstanding biography Bohemian New Orleans: The Story of the Outsider and Loujon Press and nod in approval at the gamut of famous writers Loujon published—Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Langston Hughes, Diane di Prima, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, LeRoi Jones (now known as Amiri Baraka), and William S. Burroughs, among many others. It is quite another to slide the enormous cover off the handmade wooden box that contains Henry Miller’s Insomnia, or the Devil at Large and leaf through a dozen of the author’s watercolors before arriving at the book, couched in foam and glistening metallic.

Loujon operated during a particular moment in the history of artistic publishing in America, and although it is not regarded as highly today as some of its contemporaries in the annals of artistic bookmaking, Loujon remains a distinctive and compelling entity at the intersection of fine-press publishing, counterculture literature, and the French Quarter from which it emerged.

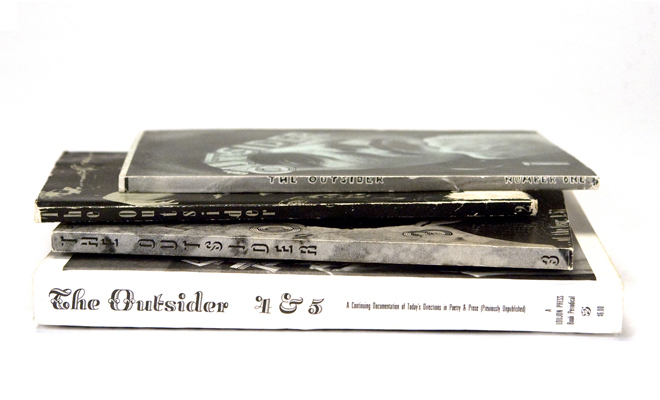

The complete Loujon bibliography consists of four issues of The Outsider magazine (1961, 1962, 1963, 1968-69); two of Charles Bukowski’s earliest books, It Catches My Heart in its Hands (1963) and Crucifix in a Deathhand (1965); and two of Henry Miller’s later books, Order and Chaos Chez Hans Reichel (1966) and Insomnia, or the Devil at Large (1970). One who examines them as a collection witnesses the evolution of the Webbs’ bookmaking abilities in terms of concept and craftsmanship, which were constantly affected by the conditions of their finances, health, geography, and equipment. Though their editorial sensibilities remained apparently unaffected by the often tumultuous environs in which they worked, the Webbs’ physical productions betray the indelible stamp of their nagging lack of resources and other external elements.

An instructive—if perhaps cynical—point of entry into the aesthetics of Loujon’s publications is a consideration of the conceptual contradictions between the two Bukowski books and their texts. The binding, paper, type, format, art, and design are all immaculate, but the ways in which the books, as objects, interact oddly with Bukowski’s poetry illustrate both the Webbs’ singular vision and the compromises they made to realize it. In his introduction to It Catches My Heart in its Hands, Shreveport native and literary scholar John Corrington extols the virtues of the plain language with which Bukowski constructs his verse. He writes, “Bukowski does not have a ‘formal’ and an ‘informal’ style; he uses only that single and singular idiom that somehow shames the strained and self-conscious efforts of contemporary academic baroques.” This statement aligns with much of the hoopla lathered on the Beat poets, with whom Bukowski is tangentially grouped, in that theirs was a language of the people, complete with stutters and slurs, rather than that of the classical elite. “Subject aside,” Corrington continues, “this is the spoken voice nailed to paper.”

Helmed by husband-and-wife duo Jon and Louise Webb, Loujon Press published four issues of The Outsider magazine between 1961 and 1969 in New Orleans. Photo by Akasha Rabut. Courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection.

The Webbs appreciated these very aspects of Bukowski’s poetry, but rather than couching it in a book that complemented his grizzled everyman’s dialect—perhaps a mimeographed pamphlet, the medium of choice for Fluxus book artists publishing around the same time—Jon and Lou presented it in a book with so many ornate and colorful doodads that Jon later referred to its style as a “bunch-of-Indians-whooping” (indeed, the multi-colored, stepped introductory pages slightly resemble a feathered headdress with their rough-cut edges).

That the Webbs were obsessed with their pursuit of producing a fine-press book regardless of its written content is underscored by the elaborate publisher’s note near the back cover, in which they describe the type, process, and paper they used: “777 copies of this book were printed by the editors of Loujon Press, one page at a time, handfed with 12-point Garamond Old Style for the poems, 18-point Pabst O. S. for the titles—to an ancient 8 by 12 Chandler & Price letterpress; on Linweave Spectra paper throughout, 320 lb. for the cover, 160 lb. for the jacket, 75 lb. for the text, in shades of white, winestone, saffron, bayberry, peacock, ivory, bittersweet, gobelin & tobasco.” Corrington’s argument in the introduction and the opulent nature of the book appear to agree only in that they both contend that Bukowski is a poet of considerable stature, worthy of both serious literary consideration and a publisher willing to exert tremendous artistry and effort on his behalf. Unfortunately, the unsubtle aesthetics of the Webbs’ book compete with Bukowski’s poetry to such a degree that the artistry and effort devoted to both are diminished.

Bukowski’s poetry is similarly disjointed from the aesthetics of his second Loujon book, Crucifix in a Deathhand, which features cover art and etchings throughout by New Orleans artist Noel Rockmore. Rockmore, a friend of the Webbs' best known for his dreamlike paintings of French Quarter street life, was prominent enough nationally that attaching his name to the book would increase sales. But his surreal, almost Dali-like images in Crucifix that depict grotesque dinner parties and industrial cityscapes don’t jive with the characters, situations, and settings in Bukowski’s poems, which in many cases extend no further than the crappy rented rooms in which Bukowski drank and wrote. The instructive element of this juxtaposition is that, according to the biographer Weddle, the Webbs’ collaboration with Rockmore resulted from their friendship, rather than a curatorial selection on the Webbs’ part of the artist whose work would most appropriately accompany Bukowski’s poetry. This reflects not only the Webbs’ eagerness to work within a close-knit group of compatriots, but also the fact that their consuming publishing pursuits left them perpetually broke, and they would have had trouble commissioning an artist of Rockmore’s stature whom they didn’t know.

Besides its poor financial status, the situational element that most apparently influenced the aesthetics of Loujon’s publications—particularly the four issues of The Outsider magazine—was the visual culture of New Orleans. The Outsider existed amidst a renaissance of experimental “little magazines” like Semina, Kulchur, Burning Deck, and Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts, and the Webbs were eager to represent their city as an artistically vibrant place alongside New York and California, from which most of these publications emerged.

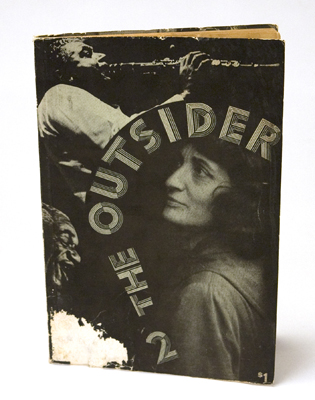

The most prominent visual homages to New Orleans in The Outsider were the “Oldest of the Living Old” sections, in issues two and three, which consisted of collages, photographs, and notes about old or dead, obscure New Orleans jazz virtuosos. The pictures of elderly musicians cut and pasted beside or on top of each other, along with handwritten captions describing their lives and achievements, give the sections the unstately and informal feel of a zine—like lively obituaries written for a culture soon dead, with a celebratory feel akin to a second line. One page even features newspaper clippings of two short obituaries beside photographs of the recently deceased musicians they elegize—the photos of the players dwarf the clippings in size, and a note on the opposite page states that the obits were “meager in their descriptions” of the players’ accomplishments. As visually vibrant as these pages appear, however, one cannot help but notice in them the tendency of New Orleans to attempt to “preserve” its culture—the famed jazz venue Preservation Hall plays prominently in the sections—coddling its artists like artifacts while they’re still viable entities.

Regardless of their conceptual stumbles, The Outsider magazines and Bukowski’s two Loujon books are fascinating objects, beautifully made and interesting for the ways in which their compositions expose the varied interests, sensibilities, and situations of their auteur-like architects. And if there are two Loujon efforts that are beyond the types of reproaches leveled at Bukowski’s books, they are the two Henry Miller books, produced in the later stages of Loujon’s existence.

Issue two of The Outsider (1962) featured an “Oldest of the Living Old” section, which was dedicated to local jazz musicians. "Gypsy Lou" Webb appeared on the cover. Photo by Akasha Rabut. Courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection.

Editor's Note

The success of these books is explored in part two of the series.