State of Affairs: Willie Birch

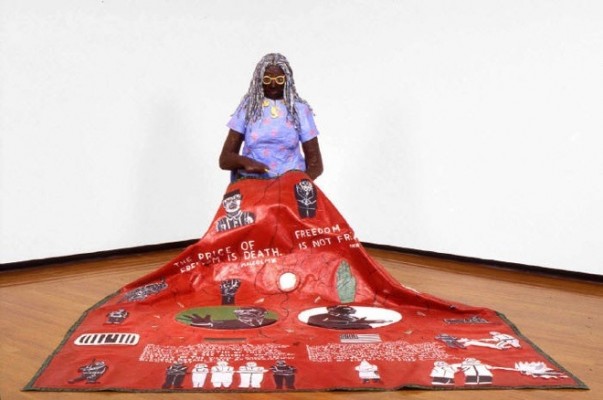

Willie Birch, Memories of the 60's, 1992. Paper-mâché, mixed media. Courtesy the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

The first in the series “State of Affairs,” which examines the current role of the visual arts in New Orleans, Pelican Bomb editor Cameron Shaw talks with artist Willie Birch. Born and raised in New Orleans, Birch has made the persistence of the city’s African-American culture his life’s work, through both his individual artistic practice and his involvement with community organizations, including the Porch, which Birch helped found in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Cameron Shaw: People often joke that you are “Mr. New Orleans.” What are you currently thinking about in your studio?

Willie Birch: I’m casting my mudclaw holes in paper to create sculptures that bear the imprint of the crawfish’s struggle to emerge from water to earth. I’m going to blow them up to nine feet or more. I’m thinking about iron because the metaphor for the United States, and New Orleans in particular, isn’t bronze. It’s iron—coming out of post-war American sculptors like Richard Serra, Mark di Suvero, and David Smith, and also in terms of African belief systems that honor the orisha Ogun. Bronze retains a sense of preciousness that I feel compelled to avoid.

CS: There’s little room for preciousness in this city.

WB: Right, given the nature of life and death. New Orleans is just too extreme.

CS: You mentioned African belief systems; do you think these ideas figure prominently in the contemporary art landscape of the city?

WB: They certainly do but are rarely recognized! In my opinion, the only African-American museum we have in New Orleans is Dooky Chase restaurant. That’s the only place you can see contemporary black art on a daily basis. There are people on the wall there who you know should be part of the larger dialogue—Bruce Brice, for example. The problem is twofold: you have a predominately white art community that doesn’t recognize African-American concerns and you have an African-American community that regards art merely as a backdrop and doesn’t fully see the significance of what its own artists are doing. It becomes a really difficult task for the black artist to get the community to embrace the work.

CS: How do we go about changing that?

WB: We talk. We curate shows. I especially rely on young people who share a sense of fairness and who recognize that we all have something to say and contribute to the recreation of this place called New Orleans.

CS: Is that where something like the Porch comes into play in terms of educating a group of young people on some of these issues?

WB: Yes, but what often gets lost in conversations about the Porch is that it wasn’t created solely for the perpetuation of a black culture that is specific to New Orleans. It is important that the kids understand that these vernacular homes that they see and the Mardi Gras Indians, for example, are not totally a local invention. They are part of a broader history that incorporates what we know about diaspora memory and provides another cultural reference point. More importantly, the Porch was created to identify young people who possess leadership qualities and to educate them so that they understand that they have an obligation to make other people's lives as meaningful as the experience that they gained through the Porch. In doing so, we can potentially cultivate a whole new generation with a different set of priorities and knowledge base.

I’m watching kids, who wanted to be drug dealers five years ago, now thinking about being other things. A young man named Raheem comes to mind. I just brought him another book and he got straight A’s last semester in school. He is a brilliant kid who just needed somebody else to say: “I believe in you.” And with that simple gesture of support, a young person learns not only about individual self-worth but also about responsibility to others, which is something that was a major part of my generation because of our experience of segregation and the Civil Rights Movement, but seems to have gotten lost somewhere along the way.

Young girls at the Porch "masking" as baby dolls for Mardi Gras, 2010. Photo by Ron Bechet.

CS: Do you think that is the role of art ideally in New Orleans’ rebuilding process—this idea of engendering responsibility and creating a platform for education?

WB: I don’t like to speak in absolutes but I continually ask myself about the role of art and, more broadly, culture. I think the most basic role of culture is to give a person a sense of identity. Now, how does culture do that? When you see Mardi Gras Indians, when you see second lines, when you see the way folks dance here, that all says something about who they are and the more they learn about the roots of those practices and their connection to other places and times in history, the better equipped they are to find strength and pride in their own culture and acceptance of the cultures of others.

CS: What about the role of the artist at this time?

WB: My personal responsibility has always been to act as a recorder, especially given my experience as an African American feeling locked out of history or not finding imagery that represented me. In college at Southern, I avoided taking a mandatory course on Louisiana history until I was a senior because I had read the book, which stated plainly: “The Negro made no contributions to the history of Louisiana.” To take that course would have been humiliating, because at that point I had already learned that kind of statement was ridiculous.

I had also learned at a very early age that if I created from what I knew—what I saw around me, which were people of color—folks would respond because they recognized some truth in it. I remember one incident when I was doing studio visits at a university in Boston, and this young lady who was from Mexico was trying to do these abstract paintings, which felt completely dead. I asked her, “Where are you in these works?” She started crying, went into a cabinet and pulled out all these little paintings that were based on Mexican retablos, and the energy in them was just palpable. I said, “These are you! This is what you should be doing because this is who you are.” We hugged each other, and I went on to the next student, but I never forgot the pain that young woman was experiencing because people were trying to convince her to create something that didn’t feel true to her. In 1971, I was the only African American in my graduate class at the Maryland Institute; so what did I do? I disguised the map of Africa in a color field format. Given my teachers’ expectations, I felt I couldn’t do what I wanted to do. As soon as I graduated, however, I abandoned what I was taught and began to try to relate my experience of growing up in New Orleans, which actually nourished my soul. That’s when things really opened up!

The ultimate lesson I learned about being an artist came from Oretha Castle Haley, who was one of my mentors. There I was, an 18 year-old student at Southern joining the Civil Rights Movement. What was I gonna paint? Flowers? While people were getting their heads busted open? I was confused. Oretha said to me: “Willie, in revolution,” which is what she called it and I believe that is what it was, “in revolution, the artist is critical because he has one foot in poverty and one foot in aristocracy.” I didn’t quite understand her meaning. She went on to explain that I could be the truth of the people, carrying the message and the expressions of the people when their voices weren’t otherwise heard. That was an intense commitment and she made it clear that it was also a privilege. I’ve carried that sense of responsibility all my life.

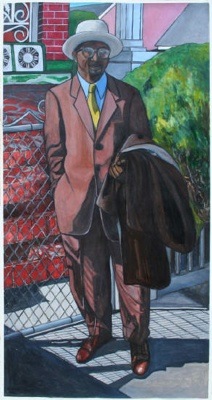

Willie Birch, Dapper Young Man, 1999. Acrylic and charcoal on paper. Courtesy the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans.

CS: The circumstances are obviously different but I would say New Orleans finds itself in a critical moment akin to that surrounding revolution, when many different outcomes seem equally plausible.

WB: A crossroads…and there is a real opportunity for positive change at this moment. I believe art has a very good chance of facilitating this change. My problem comes in having faith in the people in power to do their part.

CS: Well then what can we do on a grassroots level?

WB: My mind immediately goes to the photograph I recently saw of children in Egypt sweeping the streets of Tahrir Square after President Hosni Mubarak resigned. That’s a powerful image of community responsibility! On the grassroots level here in New Orleans, we create the Porch or other community organizations. Part of the answer is education. Resources like what you're doing with Pelican Bomb make a difference. When I first heard the name, I thought, "Why bomb?" A bomb is such a violent thing, but maybe your generation needs that kind of explosiveness. Sometimes things need to be destroyed in order to be put back together, which is a poignant idea when thinking about what New Orleans has been through. The thing to remember is everything has a shelf life, a period during which it is most relevant. The Porch is not something that was created to last forever. It was established January 15, 2006 as a rebuilding organization. So you run that baby as long as you can with certain principles and when it’s no longer relevant it will dissolve. And whether the Porch survives or not, those kids will find another vehicle. We’ve planted the seed.

CS: Thinking about the shelf life of the Porch, for example, and you saying that it was created as a rebuilding organization with a limited life span…do you feel that New Orleans is still in a rebuilding phase or has it moved onto a different phase with different concerns?

WB: Exactly. I don’t know what this new phase is called, but I resigned from the Porch’s board last November because I felt I could be more useful in another role. I’m more important in this community now just as Willie Birch, the artist. When I walk out my door, folks in the neighborhood see another face that’s not trying to sell drugs or do somebody harm. I’m making things that reflect them. I give them cards and portraits that hopefully show them something about themselves. There are very few of us. Being an artist is a very difficult thing, and then you compound that with being a black artist, but that’s where my strength lies. My strength is that I represent another model.

CS: I think this choice and the feeling you’re describing bespeaks an issue for all of us living in the city to consider. Maybe New Orleans is out of the initial rebuilding phase—out of a crisis situation—and the next phase has to be about sustainability, about people getting into the roles that best fit them and where they can best serve other people.

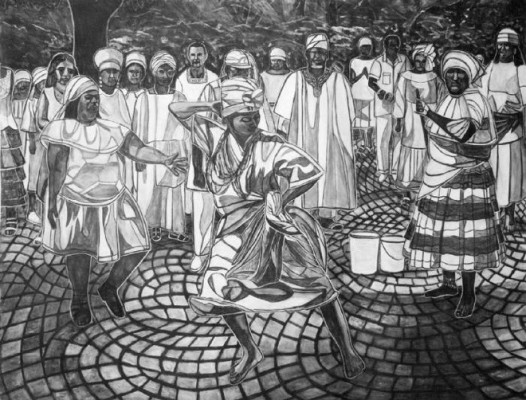

Willie Birch, Evoking the Orishas, 2003. Acrylic and charcoal on paper. Courtesy the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans.