State of Affairs: José Torres-Tama

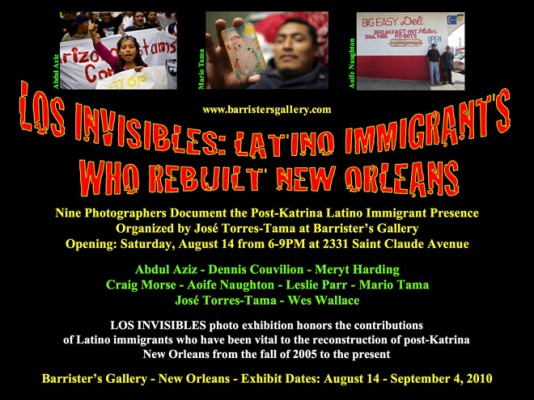

Announcement card for "LOS INVISIBLES: Latino Immigrants Who Rebuilt New Orleans," curated by José Torres-Tama in 2010 at Barrister's Gallery, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

For the third interview in the series “State of Affairs,” which examines the role of the visual arts in New Orleans, Pelican Bomb editor Cameron Shaw speaks with José Torres-Tama. An artist and activist, Torres-Tama focuses on the challenges facing the Latino community in New Orleans and nationwide through his work across disciplines. In 1993, he curated “Latin Perspectives I, ” the first showing of local Latino artists at the Contemporary Arts Center, and his most recent curatorial project, “LOS INVISIBLES: Latino Immigrants Who Rebuilt New Orleans,” was on view at Barrister’s Gallery in 2010. Examining the birth of multiracial identity in the United States, his traveling exhibition of pastel portraits, “New Orleans Free People of Color & Their Legacy,” debuted at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in 2008. Its accompanying catalogue, published by the Ogden with the support of the Joan Mitchell Foundation, will be redistributed in local bookstores this winter. Since 2006, Torres-Tama has been a regular contributor to Latino USA on National Public Radio, and his 2010 multimedia solo show ALIENS, IMMIGRANTS & OTHER EVILDOERS continues its nationwide tour with performances at Vanderbilt University in October. For the sixth anniversary of the storm, he is performing his multimedia solo show, The Cone of Uncertainty: New Orleans after Katrina, at the Shadowbox Theatre until September 11.

Cameron Shaw: Immigrants’ Rights is one of the key issues driving your work, both on and off the stage. How do you see your performance strategies fitting with your advocacy work? You reach a very different demographic with your show ALIENS, IMMIGRANTS & OTHER EVILDOERS than you do protesting an anti-immigration bill at the state capitol building or broadcasting via Latino USA on NPR.

José Torres-Tama: I often joke that art is my bad habit, but I put my energies towards developing projects in which art is a vehicle—a powerful creative strategy to tackle some of the more difficult issues of our times.

Let me give you an example that really moved me. We did the work-in-progress shows for ALIENS at the Ashé Cultural Arts Center in May 2010. I was performing a script in development and we didn’t even have any of the short films ready. During the post-performance talkback, a Nicaraguan woman stood up and said: “I’ve lived in New Orleans for 20 years. I’ve never stepped inside a theater before because I never thought there would be something about me on any of the stages here. The story that you just performed about the Nicaraguan woman who came to the United States as a war refugee, that’s my story.” She was saying this in Spanish—I had to translate—and she was in tears.

This woman’s reaction was a result of the very intentional process developed for ALIENS, and because the National Performance Network commissioned the project, I had the funds to travel to Houston and Washington, D.C. to interview immigrants in the cities where the two additional commissioning partners were located. Immigrants who had crossed the border generously shared their stories with me, like the Nicaraguan woman in Houston who inspired that character. She had not spoken about her escape for years because it was considered the family’s dirty secret—a taboo subject. She like many others had been silenced by societal pressures to keep such information private, but she sat down in front of the camera and immediately said, “Sí, yo soy illegal.” “Yes, I am illegal.” Boom! She blew me away with her candor and her willingness to finally speak about this publicly, and her story went on from there. I didn’t want to just speculate on immigrant travails. I wanted to gather stories of immigrants and hear from them what it means to live in a state of persecution.

CS: The stories you present in ALIENS are rooted in personal experiences, lending your work efficacy as a social tool. Often times when people hear hot-button words like “immigration” or “race” in the political context, their brains shut off. They don’t want to engage, but using the avenue of performance, you can sneak into their heads in a different way. I hate to say “sneak” because that implies some level of dishonesty, but it is an avenue into their consciousness that may not have been otherwise available to you. People are not always open to debating issues, but they tend to be open to hearing one another’s personal stories—not realizing that people’s stories and the issues are the same.

JTT: I come from a Latin American tradition. I was born in Ecuador. I came here at the age of seven, but I maintained my language and my connection to the culture. The poet in the Latin American tradition speaks for the people in his words; the painter paints the people’s struggle. My work is heavily influenced by the great Uruguayan intellectual, poet, and writer Eduardo Galeano, who states, “My memory will retain what is worthwhile. My memory knows more about me than I do; it doesn’t lose what deserves to be saved.”

After the storm, many narratives of trauma and displacement began to enter the mainstream media, but the story of the Latino immigrants who came to aid the city went virtually untold. The fact is this city should be tremendously grateful to the reconstruction efforts by immigrants—many are gone—but many have stayed with their families. Now these same immigrants are fighting for the right to remain, and they are being demonized by racist legislative polices. Just earlier this summer, there were two anti-immigrant bills flying below the radar that made their way through the legislative committees before being deferred. I was in Baton Rouge documenting the local grassroots groups fighting them and looking to record a new commentary for Latino USA on NPR. These anti-immigrant bills were voluntarily withdrawn by their respective legislators. It was great news for the local and national immigrant community, but it was just a brief mention in the Times Picayune. These stories of the Latino immigrant community and its many challenges after the storm are not being told. That’s why it was so important for me to organize the photography exhibit at Barrister’s Gallery last August called “LOS INVISIBLES: Latino Immigrants Who Rebuilt New Orleans.”

CS: That show was the first to visualize the struggles of the Latino community in New Orleans post-Katrina. It’s ironic because taking the issue of invisibility as its starting point, it actually generated a great deal of attention.

JTT: Barrister’s director Andy Antippas opened his doors to making this project a reality, and it remains the only visual arts exhibition in post-storm New Orleans to explore the lives of the immigrants who rebuilt this city. I was most grateful for the fact that we had a multiracial audience of more than three hundred people at the “LOS INVISIBLES” opening, but that was not accidental. We had an open call to photographers, and I sought out others who I knew had documented the immigrant workers. The nine photographers we finished with represented different viewpoints. We had a Muslim African-American photojournalist. We had Latino photographers, and we had a husband-and-wife team from Ireland that was living here through 2007. It was such a diverse audience that came, and I believe it was because we had a diverse group of artists participating. Even when I did my multimedia ALIENS solo show at the Shadowbox Theatre on St. Claude a month later in September 2010, the same thing happened. I connected with the Office of Multicultural Affairs at Tulane, and they helped me bring in African-American students. Of course, I connected to the Latin American Studies Department there, and they helped me get the word out. My relationship with the Congress of Day Laborers helped me to reach out to immigrant workers, and we were able to have them experience the performances for free, as a measure of gratitude for their work and because we had the subsidy support from an Alternate ROOTS grant award. Working with Puentes New Orleans helped me to reach out to the larger Latino community, and I worked with the Latino minister at a local church to encourage his immigrant congregation to attend. It was all done very purposefully and to have multiracial audiences on St. Claude is a feat!

CS: It’s a lesson in audience building and the proactive steps that need to be taken to build audiences because it was diverse on other levels—not just racial diversity. If you have political advocates alongside those who might not see themselves as advocates, and you have college students alongside well-versed regulars who see performance art whatever the topic, then you have a group of people who are thinking about the issues you’re raising very differently.

You mentioned the feat of having multiracial audiences on St. Claude Avenue. You’re beginning a new project, which you’ve described as an oral history. It focuses specifically on St. Claude, and I was at a panel discussion in May where you spoke about the divisions you’ve observed on this street, namely between the burgeoning visual arts community and other residents. Some artists at the discussion had a very guttural reaction to the idea of separatism, an understandable response to defend themselves. I immediately thought of Pelican Bomb as a facilitator. If readers could take in the initial information about your project and the issues you are raising and then process it on their own time and in their own terms, rather than in the context of a heated debate, then when you really delve into the project later this year and begin to interview people, those next conversations could be that much more productive. It could also extend the dialogue beyond the people you plan to interview.

JTT: I agree that this dialogue we're having can be a productive part of the implementation strategy. This project has been germinating for years. As soon as I saw the St. Claude Arts District start to bloom, I was supportive but I also had my reservations. It’s very tricky this idea of demarcating a particular place as an arts district because it’s usually the beginning of some major transformations in the neighborhood, as we’ve seen throughout the country.

I was the founder of the Marigny and Bywater Open Studios, which I first initiated in December 2004, so I have a history with artists in this area before and after the storm. I’ve lived in the Marigny since 1987, but many new folks may not remember that Open Studios was one of the first art events to bring attention to the alternative artists living in these two historic neighborhoods. We had a strong nucleus of artists that were part of the founding collective, and it included Pati D’Amico and William Warren of the Waiting Room Gallery, which was one of the very early alternative art spaces in the Bywater—if not the first. The collective was quite loose post-Katrina, but with the support of folks at L’art Noir and other artists, we organized the first Open Studios event after the storm by December 2005. The main premise was that artists were also part of the recovery in these neighborhoods, and we were.

For now, I think the best place to begin this project is a question: Why is St. Claude Avenue an arts district? Who decided that it should be recognized as an arts district, and who benefits from this designation? How does this designation and this new identity integrate with the African-American community that was here before the arts district and its artists arrived?

Personally, I benefited from my house being on St. Claude because the 2400 block where I own was practically abandoned, and the house had been on the market for a year with no takers. In 2008, my wife and I could afford the house because it was on St. Claude. We were the first family to move into this block. Today, it’s a thriving stretch with the Shadowbox Theatre at the corner and Byrdie’s coffee shop and gallery right next door. Some Latino day laborers and their families have settled around St. Claude, St. Roch, and the Upper Ninth area, since often Latino immigrants migrate to neighborhoods where the rents are cheaper. These lower rents for living and business spaces have also made the area attractive to the alternative arts community that doesn’t have a lot of capital. It is safe to say that a broad spectrum of people has benefited from the general affordability of this area, but in the future, we may be at risk.

CS: What is the risk?

JTT: There could be a potentially brutal gentrification process developing here over the next five years, one that excludes many of the current residents of color. Even the arts collectives, which are predominantly white, if they don’t buy their buildings now may usher themselves out in a few years. Not too long ago, there was a report in The New York Times about the development of St. Claude, citing it as one of the best up and coming places to buy property in the city. That is pretty serious. One of the things that I’m trying to do with the St. Claude Avenue Visual and Oral History Project is capture the present moment as this avenue moves towards its inevitable transition.

We don’t know what that transition will be like or how long it will take, and the development of a streetcar line here will no doubt make a difference. I am supportive of the streetcar, but I’m not interested in making money off the raised property values and flipping my house. Where would I go? We encouraged our friend, who was still living in exile in Austin after the storm, to buy on this block, and when she finally got her Road Home money, she bought a double Creole home at the other end in March 2009. With her little boy, she was the second family on the block, and we have anchored this little stretch. I want to live and make my art here, and as an artist of color, I want to see an integrated arts community here.

Announcement card for José Torres-Tama's The Cone of Uncertainty: New Orleans after Katrina at the Shadowbox Theatre until September 11, 2011.

CS: Is there a potential solution in this chain of events you’ve described of neighbor encouraging neighbor. If the block is repopulated by a diverse group of responsible owners, rather than renters who are highly susceptible to being priced out, then the processes of gentrification are disrupted.

JTT: Reggie Lawson is a social activist and real estate agent attempting to do just that. He helped my family get our house. He’s the president of the Faubourg St. Roch Improvement Association, and he’s working to develop programs that empower the African-American community surrounding him to buy and grow as homeowners.

But there is a parallel problem I’ve been observing. The burgeoning art scene reflects a disturbing legacy of segregation in New Orleans because there is such a dramatic lack of diversity in the audiences at many of these spaces. When I walk into one of the five galleries nearby, as a Latino café-con-leche colored man, I could say: “Well, this is just what the alternative arts community looks like.” I don’t believe this has to be true.

The great African-American artist and iconic figure Elizabeth Catlett brought her black students from Dillard, when she was chair of the Art Department there in the 1940s, to the then segregated Delgado Museum (now the New Orleans Museum of Art) to see a Picasso exhibit. She had the audacity and courage to challenge the intentional segregationist practices of the many cultural and arts institutions then, but it’s obvious that we are still suffering from the legacy of this paradigm today whether or not the intentions are the same.

So we’re seeing a major transformation on St. Claude, which is partly the result of these very interesting and engaging new art spaces, and we have this opportunity to look at the racial issues at play before it is too late. Greater integration could be seen as an opportunity rather than a burdensome issue. As both an artist and a homeowner, I want to figure out how we can be instruments for positive and integral change rather than the possible radical eradication of an African-American working-class neighborhood.

CS: New Orleans, and St. Claude in particular, then has the opportunity to become a new model, contrary to the extreme and homogenizing transformations witnessed in other parts of the country—New York’s Soho and Chelsea neighborhoods come to mind as examples. That’s a tall order. What will be required from day to day activity to effect this change?

JTT: I think Soho and Chelsea are too removed to really use as viable examples of arts gentrification for us here, but we can look more closely at the Warehouse Arts District. In 1984, when I arrived in New Orleans as a young artist, that area was skid row, full of abandoned warehouses, and look at it now. It’s of course plagued by many of the same problems. Take White Linen Night for example; it's one of the city's most important arts events and the premier night for any artist to have an opening, but I assure you that very few hands are needed to count the participants of color walking around. The major difference is that there was no real neighborhood, not like what we have on St. Claude. We have more to consider here, but I think the first step is to get people talking and listening to one another’s stories. Can we comfortably acknowledge that the St. Claude Avenue arts scene appears to lack diversity in its audiences and its artists? The process has to start with recognition.

CS: Do you think some of the solutions will start to materialize when people start sharing their stories? Do you intend to ask people what they would want for this neighborhood in the future?

JTT: Of course, I intend to talk to folks about whether they are noticing some of the things I am or not and then eventually start putting together larger community gatherings. This is where a place like the new Healing Center could enter into this project, as a venue to bring people together if it’s going to live up to its moniker and mission as a multi-use facility engaged in the well-being of the community. I also want to identify spaces important to the African-American community that could serve as meeting places. I understand the divide can go both ways.

To the artists on St. Claude now, I ask: how is it that folks right next to you may feel that the art activity that is happening in your space has nothing to do with them? Are there initiatives to inspire more diversity? Is it as simple as bringing in more artists of color? I know people want to be inclusive, but do their practices speak to that? Do they reach out? One of my performance aliases is “El Señor Boca Mucho Grande” and through this character in The Cone of Uncertainty, which I’m now performing, I dare to ask some of the difficult questions concerning post-Katrina New Orleans. I know that when some people see my name attached to the St. Claude Avenue Visual and Oral History Project they know I’m going to be speaking about issues that may be uncomfortable, like the existing racial and economic divisions in our neighborhoods, but there’s no room for denial here.

CS: But you’re not speaking about the issues yourself in this project ultimately. You’re letting people speak for themselves. Like some of your previous projects, it’s about people and their stories.

JTT: One of the epic stories that I tell in the ALIENS performance can serve as a metaphor for what’s happening on St. Claude. It's about a nineteen-year-old Latino immigrant worker who arrived in New Orleans to work two weeks after the storm, and about a year after being here, a dumpster fell on his hand, sliced it in two. He was brought to University Hospital. The nurses and doctors had never seen anything like it, and they recommended severing much of his left arm to prevent an infection. Interestingly enough it took an African-American surgeon who connected to him on a human level, who said, “I have a son your age and it is too traumatic to cut off your arm. I’m going to repair your hand and reconstruct it.” This young man is now a major leader and activist with the Congress of Day Laborers in New Orleans, and all he needed was the compassion of a doctor and a real human connection with someone who cared.

CS: I think that’s a really powerful metaphor for thinking about this street. That instead of accepting the divisions in the community and severing communication, we can think about the ways that we can restitch and heal it. It will no doubt take more work but the benefits will also be greater.