Richard Thomas: By Any Means Necessary

Richard Thomas, Keki Me Si Metose Neniwa (We The People), 2007. 29x72' mural in Waterloo, Iowa (detail). Courtesy the artist.

I caught up with Richard Thomas on Magazine Street earlier this month as he was passing back and forth between two different shops showing his work as part of Art for Arts' Sake. It was hard to get in more than a few moments of conversation with him, competing with the gallery-goers vying for his attention, so we agreed to meet up at a later date in our shared Mid-City neighborhood. He invited me to his Broad Street home, still undergoing Katrina renovations, and as we sat on a window seat to chat, he gestured to the front living room space. “I’m thinking of not furnishing that room,” he said, “but rather filling it up with nothing but paintings on the walls. What do you think?” I smiled and noted he might at least include a bench in case someone wants to spend some time in there. He chuckled and agreed. The renovations to fix the damage from 2005 have been slow going, as Thomas does the work himself, piecemeal, when he can find the time. Before the storm the basement of the house served as his studio, which meant he lost much of his painting to flooding. “It was like I had no history,” he says of the experience.

That history began in the late 1970s, when Thomas would describe himself as a “soldier of art,” fueled by anger to expose the social injustices plaguing African Americans. He fought his battles with a paintbrush, depicting gruesome scenes of racial violence. But before long Thomas started to feel his message was falling on deaf ears—an audience who didn’t seem to care as much as he did. At a group show organized by Martin Payton at the Rivergate Convention Center, Thomas overheard a conversation between a mother and her precocious young son about his work, as he stood by unrecognized. When the child expressed shock at the sight of a young black man covered in blood in one of his paintings, Thomas secretly hoped the mother would view the work as an opportunity, explaining how people should be treated with fairness regardless of skin color. Instead, equivocating, she told her son that the man was simply “covered in ketchup.”

This chance encounter stuck with Thomas, and coupled with a prophetic dream several years later, served as the impetus behind a major stylistic and conceptual shift in his work. Feeling like a voice in the wilderness, he dreamt of being visited by a tiny, tobacco-chewing elderly black woman—so old her skin was like leather with a disposition to match. Between spits she said to Thomas, “Son, why ain’t you paintin’? Don’t you know you got to paint your skin?” By that point, painting had taken a backseat to Thomas’ social organizing and curatorial projects, such as Exposition in Black, a groundbreaking group show of black Louisiana artists at the Contemporary Arts Center in the early ’80s, and when he did paint, it was still violence and hardship. He understood “paint your skin” as a call to transition his focus from the oppression and indignities suffered by so many—what he describes as painting the “blues” of the African-American experience—to the positive, celebrating the joys of black life in Louisiana—a sort of “visual jazz.” Stylistically speaking, “visual jazz” is as fitting a moniker for his work as any, as he never sticks with one particular style, always experimenting.

If there is one common thread in Thomas’ work, it’s his permeating obsession with color. And it was this newfound infatuation with Southern life and vivid color that would land him large public commissions such as the murals in the Delta concourse at Louis Armstrong International Airport, as well as the columns under the Claiborne Bridge. As the first black artist invited to design the annual Jazz Fest poster in 1989, he set a new precedent, shifting the poster away from the previous trend of ambiguous graphic designs to the now requisite portrait of jazz legends. Thomas also pioneered the dual-signed print; the first bore Fats Domino’s signature, in addition to his own, catapulting the market for Jazz Fest posters to a new level.

As his commercial success increased, Thomas opened a gallery space at the intersection of St. Claude and Spain where he showed his work and operated a non-profit youth art program called Pieces of Power. Acquiring the location in 1992, he quickly established it as a bustling neighborhood arts center. But with the major losses of Katrina, Thomas found himself unable to get it up and running again, using the space for storage instead. He hit another setback when the gallery sustained major roof damage during Hurricane Gustav in 2008, and subsequently fell into disrepair amid a tax dispute with the city.

Since Thomas closed his doors six years ago, St. Claude has increasingly become a hub of contemporary art with hopes to gain even more traction with the captive audience attending Prospect.2. Located in a traditionally black neighborhood, however, today’s St. Claude Arts District is typically dominated by white artists. It is precisely this recurring conversation of the racial divide on the avenue that has prompted a seemingly unlikely collaboration. Following a panel discussion at Good Children Gallery this past June, 25-year old artist Sophie Lvoff started conversations with African-American artist and educator Ron Bechet on how to transform St. Claude to better represent the city. Bechet recommended she get in touch with the owner of the vacant, graffiti-covered building adjacent to Barrister’s Gallery, which turned out to be Thomas. Recently, Lvoff contacted Thomas about opening his space up as part of her P2.S St. Claude Satellites initiative, organizing the St. Claude Arts District to present a unified front for the biennial.

Elated with Lvoff’s invitation, Thomas has promised his participation at the October 22 event, responding, “if we have to do it by candlelight, we will.” Reignited, he plans to open the gallery with a show of his work titled “Come Helicopters or High Waters, in the Light or in the Dark.” Without electricity or running water in the building, Thomas is encouraging gallery-goers to bring flashlights to illuminate the show. He was finally able to re-patch the roof and has set up a barter system, trading paintings for help with graffiti removal. Proceeds from the works for sale will go towards bringing the gallery space back to life. For over a decade, Thomas operated the only gallery on the block. Now he is returning as a potentially integral part of efforts to establish a more integrated St. Claude. I wonder what the Richard Thomas of 1980 would think if he could only see himself now.

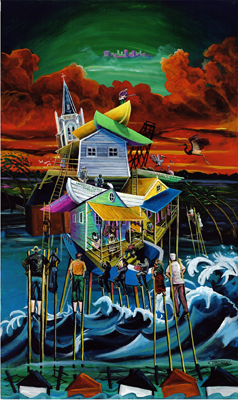

Richard Thomas, Let the Rivers Flow: We're All in the Same Boat Together, 2009. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

“Come Helicopters or High Waters, in the Light or in the Dark” on view indefinitely at the Visual Jazz Art Gallery, 2337 St. Claude Avenue. Open to the public Wednesday-Friday, 4:30-7 pm, and Saturday, 11 am-5 pm, and by appointment.