Last Call: Newcomb Art Gallery

Thomas Roma, Untitled, 1992. From the book Sunset Park (1998). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

It’s the last weekend to catch the Andy Warhol, Lee Friedlander, and Thomas Roma exhibitions at Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Gallery. As a send off, Pelican Bomb is publishing a transcript of the Making Books symposium hosted on September 14, 2011 at Tulane’s Freeman Auditorium, along with a brief introduction by the panel moderator and Assistant Professor of Photography at Tulane, Stephen Hilger.**

Born and bred in Brooklyn, Thomas Roma has been making photographs on his home turf since the early 1970s. His pictures were first seen in books and in the years since Roma has dedicated his career to their design and distribution. The exhibition "Pictures for Books: Photographs by Thomas Roma" presents an occasion to view more than 100 carefully crafted, wondrously luminous gelatin silver prints from which the artist’s monographs are comprised. The world that he looks to is fleeting, while books are authoritative, fixed, and accessible.**

In conjunction with the exhibition at Newcomb Art Gallery, Roma was joined by two longtime colleagues to discuss the book’s role in photography. Susan Kismaric, former Curator of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, selected the photographs for the exhibition. Phillip Lopate, the illustrious writer and Brooklynite, collaborated with Roma for the collection of synagogues entitled On Three Pillars.**

Stephen Hilger: The exhibition is called "Pictures for Books." Tom, from the very beginning of your career in photography, you’ve focused on the book form. The first works that you showed were two limited edition books, Brooklyn Gardens and Sirius Studies, and in the last 15 years you’ve published 12 books. I’d like to ask you: why the book form?

Thomas Roma: Well, that’s only been a question for photographers in recent years. In the past, photographers would show their work—I shouldn’t say show their work—their work was seen in magazines and books. There were virtually no galleries that exhibited photographs. It was a world of magazines and the expanded picture story, if you can imagine. Occasionally, the Museum of Modern Art in New York would publish monographs. They actually led the way, if we could just skip for a moment Steichen’s The Family of Man, which was an expanded magazine picture essay, and arrive at the time John Szarkowski gets there and a whole series of photography monographs are published. When I first got involved in photography that’s all I knew. I didn’t know that there was the possibility that collectors would buy photographs and put them in frames and then, I don’t know, look at them on the wall.

SH: What was the first photography book that really had an influence on you, or what was the first photograph that you saw in printed form that really influenced you?

TR: I’ll skip over a lot and get right to the point. I had a career on Wall Street and due to a car accident I had some time on my hands recuperating. I got involved with taking pictures looking out of a window during my recovery. It was a brain injury, as a matter of fact, which I think is a great start for a photographer! For me it took a brain injury to get me away from my other interests.

I knew that there were photo magazines, so I naturally wanted to go to the Brooklyn Public Library. I was living in Brooklyn, where I still live. I was only 19 years old, still living at home at the time, so I had my mother drive me to the public library, and I started looking through stacks of magazines. That was my entry. I understood everything I was looking at—pictures of little girls with flowers and war pictures, things like that. I happened upon a review of a book by Garry Winogrand called The Animals. It was a short review, just one column wide with a reproduction of the photograph European Brown Bear. I read the review and it infuriated me because there was no pretty girl and no flower and no soldiers. I didn’t know what the heck I was looking at, and here it was being reviewed as an important thing in the Museum of Modern Art.

I’m pretty certain in the same issue they mentioned a bookstore called the Laurel Book Center in Manhattan where this Winogrand book could be purchased. So I had my mother drive me to the Laurel Book Center. This is a curious thing: back then, this was maybe January of 1970, books stayed in print for a long, long time. They didn’t just get sent back to the publisher after six months if nobody bought them. So on that first day I bought The Animals, and I bought the great Helen Levitt book, A Way of Seeing, which completely changed my life, and several other books. I don’t want to say what else I bought, but one of the books was called The Concerned Photographer, war pictures essentially. I knew that and I got that. Then there was a book I really wanted to buy, but I didn’t. It was called Mirror of Venus by Wingate Paine. It had nudes in it, but my mother was waiting for me. It was a big book and I didn’t think I could sneak it in the car, so I never ended up buying that book. The only other thing is my life before that, the only creative output I had, was these pathetic little poems I was writing and I would collect books of poetry. So I understood books as a thing, something you could own and aspire to. And as I said there were no galleries and I hadn’t been to the Museum of Modern Art yet.

Susan Kismaric: I would add in your mention of the fact that there weren’t galleries and such. The other thing to understand at the time is that photographs were very reproducible; they are very reproducible as opposed to other art forms. If you have a Mark Rothko painting that’s 12 feet tall, when you reduce it to the size of a book, much is lost. Whereas photographs, as you said, were being made for magazines. So it’s a very democratic medium, in that sense, or it has always been regarded as democratic. I’m wondering if that aspect of dissemination plays into your interest and your dedication to books. Because the art world is a pretty exclusive world, the wonderful thing about photographs is that they can be reproduced, yes?

TR: Yes, but some of the concerns of the art world cross over into the world of publishing. You do have to be popular, or profitable, saleable, marketable, something like that. How can I say it? I was modest in my ambition. I thought someday I’ll have a book published also. A lot of the people waited. That Helen Levitt book I was talking about, A Way of Seeing, was published in 1965, and the photographs were made in the ’30s and ’40s. That seemed absolutely fine to me. That’s what you did: you worked for a long time and then you would get what you deserved. There wasn’t this other idea of becoming famous or a celebrity. I was just mentioning on the way over here that after I left my job on Wall Street, in 1971 I met Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank. In the first three months, and the reason I could do that is that none of them were celebrities. There was no such thing as a photographer who was a celebrity. You could go ring their doorbell and they’d open the door. It was that easy.

SK: They weren’t regarded as heroes...

TR: I’m sure there are heroes in stamp collecting! Photography was a sub-culture and we accepted that. Those of us who were doing it would meet in the cafeteria at the Museum of Modern Art or at various schools—Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, Cooper Union, the School of Visual Arts. We were proud of the fact that we were the cognoscenti, and we knew something that other people didn’t know. We knew that Eugène Atget was a great photographer. Although I didn’t really believe that at the time, I pretended I did. I pretended I was smart enough to know that he was great. They looked like old, brown pictures to me, but I went along with it. I liked Edward Weston pictures of seashells and, you know, fruit that looked like nude bodies or something. I didn’t know what the hell I was talking about. We learned as we went along because there was no pressure to get any better at it because there was no market. There was no money involved.

Phillip Lopate: I came to still photography through my love of movies. I was and remain primarily a movie buff. One of the things that attracted me to photography books was that they felt more like movies. There was a kind of liquid rush from page to page, from image to image. I was very attracted to Weegee’s books, and Helen Levitt’s. Someone like William Klein, for instance, he would put together a book and it was very exciting. He also then made movies, but it was very different from seeing a photograph on the wall. The interaction between images, the sequencing between images. If you looked at Brassaï’s Paris by Night there was a greater sense of a whole world so each image was less precious. There was less of a burden to genuflect in front of any one image. You can just turn the page. So in a way there was something more modest about photographs in a book than on a gallery wall. I think you can see this when you look at Tom’s books. It’s not like every picture is demanding a lot of intention, but you give yourself over to it. You lower your temperature, so to speak, and then before you know it you’re in this web, and that’s what the book is.

TR: I just want to mention since you mentioned film and Helen Levitt that Helen also made films. A while ago a friend of Susan’s and mine, Michael Almereyda, a fabulous director and screenwriter, asked me to be the director of photography for a movie of his. So I went to Helen—Helen also knew Michael—and I said, “Helen, what should I be thinking about making a movie?” She responded, “Oh, movies are easy.” She said, “What you do is difficult. It’s a lot easier shooting a movie because you don’t have to get it right. You can move, you can move the camera. There’s time, there are connecting shots.”

PL: There’s a whole subject we can go into which is when still photographers make movies—you think of Moholy-Nagy, Bruce Davidson, Rudy Burckhardt, or Jerry Schatzberg for that matter. It’s always seemed to me that when still photographers make movies, their movies tend to be muzzier and messier, and for some reason when they go into movies they think of it as a more ragged form. Whereas people who start out making movies may be more in control of an image and much more careful, it’s almost like still photographers want to take off their jackets when they make a movie.

TR: I would take off a little more, actually. That’s why they kicked me off the film...

[The panelists turn their attention to a photograph by Helen Levitt on the projection.]

Thomas Roma, Untitled, 1974. From the book Found in Brooklyn (1996). Courtesy the artist.

PL: So this is street photography. Do you see yourself as a street photographer? Do you place yourself in that tradition?

TR: Well, I couldn’t do anything to get out of the tradition. It’s an interesting idea, this idea of street photography. If I make 1970 my point of entry to photography, it was exactly the moment when the dominant figures in street photography decided that it was going to be a dirty word. We were never to call ourselves “street photographers.”

PL: Why was that? Joel Meyerowitz wrote A History of Street Photography and shortly after that Joel said, “I’m not a street photographer anymore.”

SK: Because it’s a misnomer, really. Because anyone who’s photographing out in the world tends to be labeled a “street photographer” because no one knows how to label them. We never use the term at MoMA. Just as we never use the term “documentary photography” in relation to Tom’s work or Garry Winogrand’s work. They’re inaccurate. You’re not always on the street.

TR: So Garry Winogrand, who’s a kind of prophet—I would say maybe Helen was a saint and Garry was a prophet—he was hysterical on the subject. He said, like a real New Yorker [Tom affects an accent], “What?!? I photographed in a zoo, there’s no street there! There’s no street!” And John Szarkowski, who was maybe our Abraham Lincoln...

SK: Or the God...

TR:...or the God of the whole thing, he was always struggling. He would call me up and say, “Perhaps we should call it ‘ambitious photography.’”

SK: Which you used for years...

TR: Yeah. And I said, “John, that stinks. I have no ambitions. Let’s have a drink and talk it over while we’re drunk.” Then we started calling it “straight photography” but that was right after Stonewall, so straight photography seemed to keep homosexuals out of it, which wasn’t the intention. But I actually like "street photography," but I like it for a different reason. I do photograph in the street, and I photograph in every way anyone has ever photographed.

I worked on a retrospective exhibit of Garry Winogrand’s at the Museum of Modern Art. I looked at a lot of his contact sheets. He was a friend and a hero of mine. It was only by looking through the contacts that it occurred to me that because he—a physically imposing character—was the one holding the camera, the street changed around him. So we see a photograph of a woman maybe looking sideways, the light going across her face, and her skirt slightly open a slit, and all this, but the pictures leading up to that show someone looking, noticing Garry, and then looking away. There’s no such thing as a completely objective photograph.

Thomas Roma, Untitled, 1986. From the book Found in Brooklyn (1996). Courtesy the artist.

PL: Well, of course. I just want to put in a word for the notion of street photography. It doesn’t appall me, and I’m a city rat, if anything. It seems to me that one of the things that’s being asserted in the phrase “street photography” is the importance of public space. So even if you shoot in a lobby or an elevator, by calling it “street” we really mean public space, and we also mean something democratic.

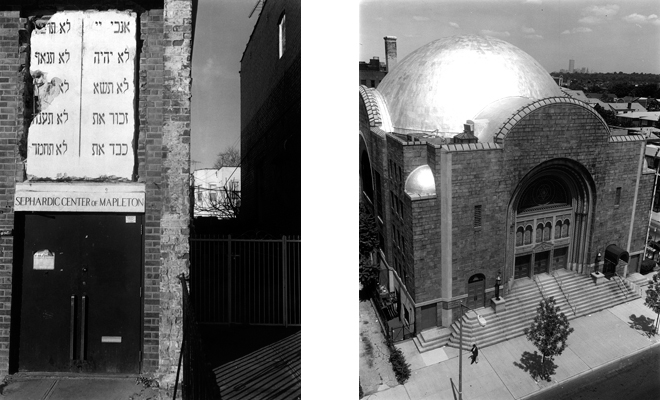

Then in terms of your photography, I wrote the text for the book On Three Pillars, which was shots of synagogues in Brooklyn, or temples, or ex-synagogues in Brooklyn that had become churches or something else. In any case, what I noticed when I looked at the photographs was, they were not like classic photography. They had more of the street in them. Again and again, you’d see lamp posts and traffic lights, the garbage bags, the line of the sidewalk, the car parked on the other side, all this stuff that usually you don’t see in architectural photography. Most architectural photography abides by the principle of the building as narcissist, enshrining the piece of architecture and cutting out as much as possible. But yours always had that horizon line of the street, if you will, and what urbanists call "street furniture," which is all that other stuff. To me, even when you’re photographing buildings, you’re photographing the street.

SH: I want to take a moment, Phillip, to mention your commentary in the book On Three Pillars. There are three things you mention in the essay: one is the history of Jews in Brooklyn, one is what you call the “architectural problem of synagogues,” and then you discuss Tom’s photography practice itself, and perhaps why he’s photographing the synagogues. Could you tell us a little bit about any of those three, but particularly about the “architectural problem of synagogues?” What do you mean by that?

PL: Well, first of all, Tom asked me to write the text for his book. He seemed to have read enough of me in the past. We’re both Brooklynites, and there was a common sensibility. One of the things I should point out is that Tom said, “You don’t have to say anything about my photographs. I just want you to write a text about what’s being photographed.” Of course that became a challenge to me, and I knew I had to talk about Tom’s photographs because I wanted to. This is in opposition to so many photographers I have known who regard the writer as a publicist and megaphone for the photographer. They very often have a hard time realizing that writers are also artists in their own rights and they basically want to get the word out about their photographs and want you to be the stooge who will do that.

TR: Boy, that’s accurate by the way!

PL: Tom was coming at me from another direction. He presented me with this whole collection of fascinating photographs, and I began to research it. Why do they look so different one from the other? I realized, first of all, that in Europe before the end of the 18th century Jews were not licensed as architects. It was forbidden for them to enter that profession. So you didn’t have a tradition of Jewish architects in Europe or America. What you had were Jewish communities that hired Christian architects. When Brooklyn became the largest center of Jewery in the world in 1950—that is it had more Jews than any place in the world—it had one-sixteenth of the Jewish population living in this one borough. It became a center of Judaism, which meant a lot of different approaches, so there was a lot of disagreement about how to design architecture.

Tom steered me in certain directions. For instance, in Orthodox synagogues, they always had two doors because one was for men and one was for women, and they went to different parts of the structure. Also Orthodox Jews didn’t like human figures. It’s a sort of iconoclastic religion, at least at that level. There could be a Lion of Judah or there could be a Star of David, but there couldn’t be a human figure. They had to figure out what the style of the building should be. Their first sense was that it should allude in some way to the original temple, but nobody knew what the temple looked like. So they started building things that had Greek tenets because the Jeffersonian architectural style was popular in America. And then that seemed dated, so they said, “well maybe we should build Gothic synagogues,” as this was a period when the Victorians were heavily interested in this. But the Gothic was so identified with Christianity that it seemed a little presumptuous, so they moved towards the Romanesque, which was also identified with Christianity. Then they had this kind of love affair with what was Orientalism—you might say an Oriental or Egyptian style. That caused other problems because a lot of the German Jews looked down on Eastern Jews, and didn’t want to be known as attached to the Orient. Finally Modernism came along and solved a lot of problems by being bare and square. All of these choices that had to do with theology and with not wanting to rock the boat, not wanting to offend your neighbors—they all filtered into these photographs. And Tom helped me to see that there was a way of reading these photographs where you could understand a great deal about the sociology and the history of the Jews of New York.

TR: Everything you said, that’s why I asked you to write for the book. I should mention, that they’re arranged in pairs in the book. Whenever it’s a pair, it’s a former synagogue and a currently operating synagogue.

Thomas Roma, Untitled, 1982. From the book Found in Brooklyn (1996). Courtesy the artist.

SK: Phillip’s essay is wonderful, if you have the opportunity to read it. I learned a lot—why synagogues are often really strange looking. Tom, you haven’t said why you started photographing synagogues…

TR: This is 16 years of photographing synagogues. This wasn’t overnight. I had the idea to do it because I decided I was going to photograph every denomination of every kind of religious practice that exists in Brooklyn. I began doing it, and it was just too difficult. Like many things we begin—whether a romance or a career—we begin in ignorance, and we might find ourselves in over our heads somewhere along the line, maybe two or three years in.

The real answer is: when I was a boy, every Sunday we would go to the Borough Park movie theater. To get to there, I had to pass the synagogue that became the cover of the book, and it seemed like one of the most magical things in the world. Very often when I got to the movies it was Ben-Hur or the Ten Commandments or The Greatest Story Ever Told. It was filled with these...

PL: It was the era of the Jewish epic!

TR: Yes! And I felt as though I was living there. It filled my imagination. I was immersed in Brooklyn Jewish culture from the time I was born. And as I mentioned earlier, Garry Winogrand, Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander, hanging with them I continued to be immersed in a New York Jewish understanding of culture. So this was my love letter to Brooklyn Jewery. I gave myself to it. I didn’t know it would take 16 years, I never would have done it, but it was infinitely fascinating.

The reason the book has synagogues and former synagogues is because after 2001 in New York, people were very suspicious of anyone photographing synagogues. The FBI interceded and knew where I was and what I was doing. I was at first angry and then humbled by that. I realized I was probably upsetting people without knowing it, and that was not my intention.

It occurred to me, I’m trying to do this good thing and the FBI is investigating me. In puzzling what to do about that, I decided to look at sites of former synagogues. So my wife and I compiled a record of all the synagogues that existed in Brooklyn the year I was born, which was 1950, and we cross-referenced them with the existing synagogues. Those that were not there, we hunted down. We tracked them down, day after day. We did it, and there was something mysterious about finding a place that was often a vacant lot.

PL: It’s a ghost story. You’re photographing something that used to be a house of prayer and now it’s turned into another kind of house of prayer, or maybe it’s turned into a supermarket...

TR: It occurred to me that in the history of Judaism, Jews left Brooklyn not because they were being persecuted but in part because of Levittown. They were able to move to the suburbs, to a nicer place, without being pushed out. Of course many, many stayed in Brooklyn and are still there. When the synagogues are gone, it is sometimes because of this aspiration, this opportunity. It’s an American story.

SK: Where does—and forgive me for not remembering—this book fall in relation to Sanctuary and the other books?

TR: All these books have an organic way of coming into being. I started doing these houses of worship, very nondenominational. I even photographed a few mosques before I lost interest. Then I realized that my real interests were in all these Christian places and Jewish ones—some are called synagogues and some are called temples and some are called houses of prayer, which is the truest interpretation of the word. But somewhere along the line—it’s another long story, I won’t tell it—I ended up being invited into a black Christian church.

SH: I actually think you should tell us this story. Because you were photographing...

TR: Okay, so I was photographing in all these religious places and a young man in Brooklyn named Yusef Hawkins was brutally murdered in a Catholic Italian neighborhood. Reverend Al Sharpton had one of his marches through the neighborhood, and I went out of curiosity. While I was there I encountered an angry mob that was mostly angry at me because I was trying to be reasonable about the situation and young people were listening to me. So they ran me out of there with the help of the police. I have to admit, melodramatically in tears, I decided if Yusef Hawkins couldn’t go to Brooklyn then I’d go to his neighborhood, which was East New York, which was one of the most violent neighborhoods in America at the time.

My first day there, I was photographing a former synagogue that had become—I didn’t realize—a Nigerian church. The pastor came out and asked me what I was doing. I called my project God’s Work at the time and when I told him that he laughed right in my face and said, “That’s not God’s work; God’s work is what we do inside.” I had never photographed in doors before. I had always been a street photographer. He invited me in, and the next Sunday I started on that project, which ended up with a life of its own. Because of that work, I had an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1996. Because of that exhibition, I had a career all of the sudden, even though I’d been working and teaching all those years. Every book I ever wanted to do I could get published. You have an exhibition at MoMA, with a catalogue, and get Henry Louis Gates, Jr. to write for you, then you can publish just about everything else.

SK: Could you talk a little more about these pictures? How did you gain entry to the churches? Did you just ask?

TR: Come Sunday was shot at 52 different churches and over 150 services. I had visited 200 churches but didn’t have access to 150 of them. I never asked permission because I think that’s false. How can you ask permission to make a photograph when the people in it are probably never going to see the photograph? Rather what I did was look at the order of services and imagine when the pastor might walk in. I would accost the pastor before the service and tell him who I was and what I was doing, then give him the opportunity to invite me in. If he wouldn’t invite me, I left. I believed I was doing something good, and he would have to take me on that account. I photographed each church at least three times. I had no idea what they were doing in these services. A lot of it looked like magic to me, and beautiful magic, I must say. I was reverent. I studied Torah for two years with Hasidic rabbis. I was reverent doing that as well.

PL: Can I say something about these photographs? You may completely disagree, but a lot of Roma’s photographs are of people’s backs or there’s a fence in front. Most photographs leap on you like a dog, but many of Roma’s photographs hold you at a distance, or there’s something you have to move through to get to whatever is supposed to be the main focus. Or maybe they don’t have a main focus at all. A lot of times there’s something more diffuse than that. You have to look over the whole photograph. So to me, there’s something anti-rhetorical about them, and they also have a sense of restraint. There’s something in his work that doesn’t want to be in your face.

SK: In turn, as a viewer, everything has to be considered. I mean that’s always true in a photograph. That’s what makes a photograph, even if it’s rhetorical and the thing is jumping out at you, because whatever the thing that’s jumping out at you is, it’s placed in the picture plane in such a way so that it does jump out at you. But in a picture like Tom’s that is less in your face, everything becomes wondrous in a certain regard.

PL: It’s interesting because if you get to talk to Tommy Roma he dramatizes himself all the time. Either he’s just about to die or some other terrible thing, but you know it’s funny because his photography is not that way.

TR: When we speak of these books, I have this magic number of 18, which is significant in the Jewish tradition. It’s the value for Chai, meaning “life.” This is me dramatizing myself. I plan on publishing 18 books. I’ve done 12 and I have two more coming out. Then I’m going to stop. And I’m never going to photograph again and I’m never even going to talk about it again. I’m going to ride a motorcycle or something. My idea is that each book is part of this thing, is a facet. The first book I ever did, the limited edition book, I have a manifesto and it’s in the form of the poem that accompanies the book. It’s a poem by Robert Frost called "A Mood Apart," and the last two lines are, “for any eye is an evil eye that looks in onto a mood apart.” I mean, after all, that’s really what we’re doing; there’s an intrusion.

PL: Could I say something about that? He’s here so I have the opportunity to put him on the spot. Tom, you said, “I went into these churches and I felt I was doing good.” Just last Sunday, I did an event with Joel Meyerowitz who was photographing Ground Zero, and he too said the equivalent: “I was in service; I was doing good.” What is it with these photographers that they all think they have to do good? Is it that this is the delusion they are under? They can’t just say look, “I’m a mean opportunist; this is who I am. I’m curious. I’m not particularly doing good.” Or is it that the profession is self-selecting so that the best ones like Meyerowitz and Roma actually do develop this reverential attitude towards life as it is?

TR: My understanding of photography is that there are three things that happen to you if you give yourself to this business. I call it a business even though money isn’t involved. One thing you have to face is the world, and it’s wondrous and it’s infinitely complex. Who even knows what’s going on in Mexico City right now or Calcutta or even down the street? Since you can only be in one place at one time, to be a photographer is to be overwhelmed to have the world as your studio. The second leg in this tripod is the medium. Although it’s only been around about 170 years, the medium of photography is so vast that you could throw out my top ten favorite photographers and it would still be an incredibly great medium.

SK: You could even throw out the known photographers, the famous photographers, and all those anonymous pictures that are left are incredible...

TR: What’s left then is the photographer, which is pathetic, the weak link. So now what do you do with that recognition? I mean humble isn’t even the word in the face of the world, what’s going on right this second, let alone the history of the world. All that’s left is to do something of some service. We don’t make photographs for ourselves. We see very well for ourselves; we all do. The photograph is not seeing; it’s making a new thing. It’s neither the world nor the medium. The world instantly changes when the photographic print is finished because we’ve then added something to the world. This photograph from Found in Brooklyn [referring to an image on the projection], that place obviously is not there anymore. That was in 1974. Even the day I took the picture, the wind blew, the chair straightened up. The picture is the new thing. I don’t mean in the service of something that’s just. I don’t know what the hell people are doing in Christian churches. I’m not promoting Christianity nor Judaism for that matter. I want to add to the conversation about religious art. We exist, and I want to be one of the people who went on record.

SK: Is it of service to you, as a person?

TR: I haven’t achieved this zen-like state, but as Garry Winogrand said, ”When I photograph, it’s the closest I get to not existing.” I believed him, and I’m trying to find that place. It’s not about me.

SK: Well, it’s like being a writer.

PL: I never said I was trying to do good…

SK: You are or you aren’t?

PL: I’m not such a nice guy. I’m not a bad guy either. It’s just that I don’t think of writing as necessarily doing good. It’s just a simple thing, but I completely buy what you’re saying that you’re adding something to the conversation. Your photographs of churches and synagogues pose questions such as: what is spiritual? What is purity? Where is the place for impurity in the spiritual conversation?

SH: I would say that’s not limited to just the pictures of churches and synagogues, but also the pictures of everyday life in Brooklyn and Sicily. In your second book, Found in Brooklyn, which is a collection of more than 25 years of photographs, the writer Robert Coles remembers William Carlos Williams’ poetry: “Outside, outside myself there is a world, he rumbled, subject to my incursions.” And Coles, who describes you as the son or grandson of William Carlos Williams, and following his lead, then goes on to call you “the poet of the camera, the localist poet, this poet, in Williams’ phrase, ‘with his bare hands walks, stalks his home town, keeps us resolutely outside those homes, garages, stores, schools, and yet so doing, brings us up close, indeed, we’re given what he found, the soul of a place as it is, and as it gets lived daily.’” I think there’s spirituality in the everyday...

TR: I would love to have heard what Coles would write about Garry Winogrand. He didn’t have the chance. I accepted a tradition the way a chess player accepts a chess board and decides not to make it bigger or smaller or change the shape or the movement of the pieces. I accepted the idea of black-and-white photography because writers don’t have to write in color necessarily. Phillip, it gets back to that earlier point about writing. Those of us who practice a medium with no ambition to entertain as the primary service are doing something good because we’re insisting that life is more complicated than you might take it if you walk down the street without looking. Our aging bodies, our conflict in relationships, we forget to consider the most serious things in life; we just forget. That’s what I think artists do; they give us the opportunity to remember the things that are worth remembering over and over again. This is what philosophers struggled with: what’s worth remembering? We have something, and then all the sudden we get a little cynical and then we forget. Art has the power to bring those things back to us.

PL: I wanted to ask about the local in your work. You did Found in Brooklyn, which is a phenomenal book in my mind, and a lot of your photographs are connected to the places where you lived. I always think of Brooklyn in relation to Manhattan—Manhattan is the peacock strutting around and Brooklyn is the relative schlepping in the background keeping the farm going. Brooklyn has always been disrespected in some way. It doesn’t have the glamour of Manhattan, and there’s something nondescript—it’s a funny word to use— something a little bit shabby about it. Certainly in the public’s mind we associate it with a working-class environment: Ralph Kramden, “Forget about it!,” all that kind of stuff. These are the clichés and caricatures of Brooklyn, but there is something to them. That in and of itself is a sort of boasting about something one usually wouldn’t boast about. So what is it for you about photographing the environment of Brooklyn? Is it the light, the way the buildings are, the fact that it’s largely a residential borough?

TR: I believe I was most influenced by the poetry of Robert Frost. The vast majority of his poetry—if I could say it’s set—is set in New England. The first book you’re not so sure, but by the second book, North of Boston, we know where we are. He made it very clear that we are north of Boston. There’s something about access, the idea that we could reach the universal. And I had access to Brooklyn.

I took the limited schooling I had very seriously. When I was a boy I went to public school. I only finished the tenth grade, but the part that was most impressive to me was studying the great explorers: Magellan, Vasco de Gama. I would make maps. We moved a lot. I moved 13 or 14 places with my mother and lived with various relatives and other places that I don’t want to think about. Wherever I moved I made a map to get back to where I used to be. Map making became very important to me as a way to locate myself. I knew where the churches and the synagogues were, and where the supermarkets were. I used to do the shopping for the family. I knew where I was.

SH: Most of the work that you’ve made has been in Brooklyn, with the exception of maybe three or four series. We’re talking about a sense of place and also a type of consistency. Overall, looking at the different photographic projects you’ve been involved in, would you say your work is more consistent or more versatile? When you look at photographing churches, photographing in the courtroom, photographing with a hidden camera on the elevated train, photographing at a public pool...

Thomas Roma, Untitled, 1992. From the book Come Sunday (1996). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist.

TR: I think there are two things to talk about in art—only two. They’re both feelings. One is the feeling when you’re walking through the woods with a group of people, and the person in front of you accidentally lets go of a branch and it whips you across the eye. There’s that feeling. The second feeling is when your dog runs away and never comes back. Now, those are the two feelings, and everything else is the lack of one, two, or both of those feelings. So we can allude to joy or pleasure, although I don’t know why art needs to. We can do that with entertainment, we don’t need art for that. But we have to be reminded that we’re not getting a branch whipped across our eye this very minute or that our dog didn’t run away, or maybe it did, and we got a new dog. I’m trying to do it all. I’m literally trying to photograph everything that I understand of my life and mostly I don’t. I’m mostly very angry, but at least I’m fully engaged physically in the world. Being in photography, I’m actually out in the world, and I let the world affect me. I can be wounded by it—I don’t think defeated—but then I can do something with that.

PL: I think a lot of your photographs have this quality of loneliness in them, and then underneath it all there’s a consolation to the loneliness.

SK: Pictures for Books is the catalogue for the show. As someone who put that book together and who puts books together occasionally, I always have an invisible narrative. So the boy in the beginning was Tom to me. I put this as the first picture in the book and it’s Tom imagining Brooklyn.

TR: That image is also in Found in Brooklyn. And Phillip was right about tricking writers. When I was working on that book, I flew down to Duke University to meet with Robert Coles. I had my humble book dummy and I asked him if he could think of someone who would write for it. He flipped through the book and when he got to that picture he said, “This is you! I’ll write for this book.” That is what I wanted, but I didn’t have the nerve to come out and ask him.

SH: I thought the question I asked you might have given you an occasion to also talk about versatility in the medium as far as the different ways that you photograph and the specific ways you’ve approached different projects. You have mentioned that there’s this assumption that the photographs you make depict something that’s real and objective. You don’t feel that way, do you?

TR: Not at all! Photographs only mean what they mean to the people looking at them who have their own life stories and make their own assumptions. The big mistake would be to look at any photograph and assume you know what’s going on because you don’t. If you make the photograph thinking you’re illustrating what was there then you’re using the medium in its weakest possible way. We know that photography is a weak medium of illustration, so we’re free to forget about that and instead use it for what it is, which I think is a fabulous medium of discovery.

PL: Looking at this scene from Sunset Park, why do you think that’s a weak illustration? That seems to me like it’s a fairly specific illustration of that day, with those kids.

TR: It might be, but I have maybe 12 exposures of that. The woman on the left has emphysema now because I made her smoke so much to make that picture.

Before Come Sunday I had never photographed people at close range, so in order to do it, I got permission to photograph at the Sunset Park pool. I don’t like the word “staged,” but I directed all these pictures so I could learn how to focus and crowd the frame. I was much more of a landscape street photographer before this. So everyone there—everyone, even the guy walking in the back, walked back and forth, back and forth. I shot that over and over and over and over to try to figure out how to arrange things in space. Nothing there is organic. There’s nothing about the photograph that’s true, except your own feelings about it.

Thomas Roma, Sephardic Center of Mapleton (left), 1991, and Temple Beth-El of Borough Park (right), 1991. From the book On Three Pillars (2007). Both gelatin silver prints. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

The Making Books symposium was sponsored by Tulane University's Interdisciplinary Committee for Art and Visual Culture (ICAVC) in conjunction with the Newcomb At Gallery.