How to Hang a Show in New Orleans

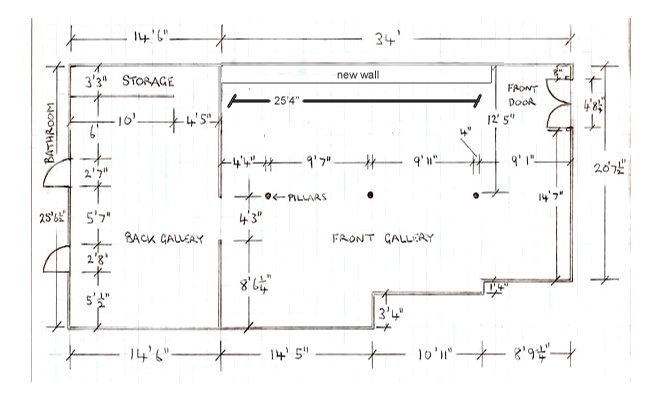

Gallery floor plan. Courtesy Good Children Gallery, New Orleans.

A work of art contains its own center of gravity, though that energetic center isn’t always immediately apparent. Finding it can require effort from the viewer, but the groundwork for that search is laid before he or she even enters the gallery. Presenting an art object is a discipline. It requires more than banging a nail into a wall or clearing a roomy corner for a sculpture. It’s about developing relationships between works and with the viewer. If a viewer has any chance of making an emotional or visceral connection with a work of art, then conditions need to be set to enhance that potential experience. The parameters of those conditions have shifted over time, as any trip to a historical collection will tell you: think the Frick Collection’s crowded Baroque salon-style hangings versus the Rothko Chapel’s airily meditative approach.

Lately in New Orleans, however, I’ve been walking out of shows of new works without the sense that I’ve made proper connection to them—a connection I’m confident the artist wants me to make. Jan Gilbert, a local artist, recognizes the dilemma. “Generally speaking,” Gilbert says, “there is a very narrow, predictable range of accepted codes for hanging shows here. It’s rare and quite memorable when exhibitions deviate and allow one knockout piece to take over a space and breathe, reverberate, dominate.”

There are multiple reasons why a work of art might not be the dominant factor in its environment. Commercial galleries want to enhance the possibilities of sales by presenting as much work as possible. Artists in collectives pay good money to be part of those collectives and are granted only so many shows per year; they might want to pack as much into those shows as they can. Doyle Gertjejansen, an artist, professor, and former director of the UNO Art Gallery, believes the problem resides elsewhere, within the consciousness of a generation increasingly influenced by technology. While Gertjejansen’s preference is for a spotless white cube to offer the singular and intimate experience of one person standing in front of one work, he contends that “at some point, probably in the late ’70s or ’80s, art became influxed with other artistic arenas like music, like performance. At that point the idea of a one-to-one relationship with the object totally changed. It became more about a mass audience. The way younger people are looking at the function and notion of art today is not so much to show the art as it is to create a forum for discussion.”

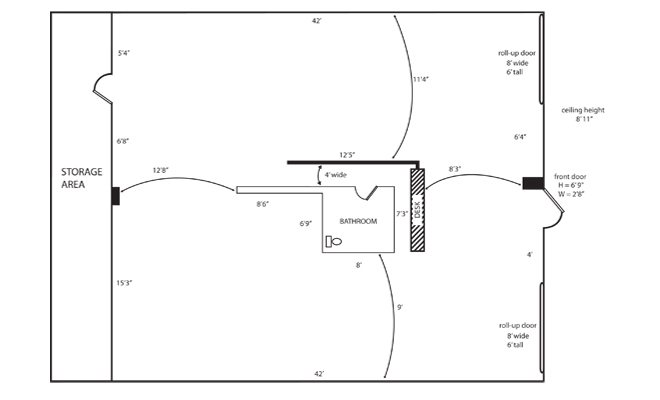

Gallery floor plan. Courtesy UNO St. Claude Gallery, New Orleans.

Artist Kyle Bravo, a founding member of The Front, disregards ideal notions of one method for displaying art and instead suggests that artists look to their work to dictate its own terms of exhibition. “Showing innovative work is the priority, and perhaps more innovative approaches to installation might result. Many people could stand to think more creatively about how the work fills the space.” Bravo continues, “Is hanging everything at eye level the best approach? What about salon style? Should works be very close to each other or have lots of space? In a grid? At random angles? What about putting work on the ceiling, on the floor, leaning on the wall? Framed or not? Projection versus monitor? Do the walls have to be white? I think too many artists think up to the point of making the work, then don't think at all about its installation or its presentation. They just throw it up on the wall and they're done. The way the work is presented is a huge part of the way the work is seen, read, and understood by viewers.”

All the interviewees acknowledge that presentation itself is a discipline, and one that currently lacks attention or creativity in New Orleans. Jan Gilbert agrees, “There is a lack of seeing each exhibition and the space it occupies as a blank three-dimensional canvas—to imagine how an overall encounter for the viewers might be orchestrated.”

While Doyle Gertjejansen doesn’t want locality to be an excuse for ignoring thoughtful presentation, he does recognize that New Orleans, as compared to an art center such as New York, possesses its own flavor or sensibilities. “In New York City, [galleries] are more like walking into a library,” Gertjejansen claims. “In New Orleans, it’s more like walking into Jazz Fest. There’s always going to be something in the city that looks exactly like the room we’re in right now [the Hey! Café on Magazine Street, where tables are surrounded by a few pieces of artwork hung about the room]. This is what New Orleans looks like. That really pristine setting, I don’t know if New Orleans would even be intrigued by it. I think it does keep us from relating to the art experience, but that’s also why I like to believe that younger people going to galleries is more like a sampling experience, the same kind of sampling experience that reflects the world they live in. And this is an opportunity to actualize that. There’s not this single pristine experience that they’re shooting for, it’s sort of multiple experiences.”

Arthur Roger, owner of the Julia Street gallery that bears his name, believes in the end it all boils down to economics. “It’s a desperation for sales, to be honest. New Orleans has always been poor. The shortage here is the collector base, so you don’t have a collector base that’s raising the bar. The galleries are raising the bar on their own just to keep it hopefully interesting. In a lot of other communities your collectors would have an expectation that you would need to meet a certain standard of presentation. The presentations are museum-like to show that you take yourself seriously, that you’re going to be around and that the work is going to be around.”

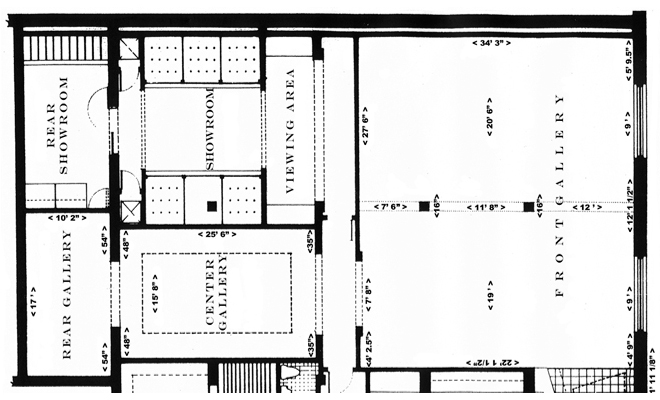

Gallery floor plan. Courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans.