Absent Populations: Deborah Luster’s Tooth for an Eye

From the book: Deborah Luster, Tooth for an Eye: A Chorography of Violence in Orleans Parish, 2011. Published by Twin Palms Publishers, Santa Fe.

I first encountered Deborah Luster’s work at the Prospect. 1 Biennial in New Orleans in 2008, when a selection of photographs from Tooth for an Eye was displayed at the Old U.S. Mint, a hybrid treasury museum/contemporary arts venue. In the series of large-scale, circular-format, black-and-white photographs, Luster documents sites in New Orleans where murders have taken place.

It wasn’t until I saw the work in a different location, at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York this February, that I noticed the extended title given to the project: “A Chorography of Violence in Orleans Parish,” also the subtitle of the book published this spring in the wake of the exhibition. Upon first reading, I misread “chorography of violence” as “choreography of violence,” possibly because I’d never seen the word “chorography” before coming across it in Luster’s work.

According to Ptolemy’s 2nd century BC text Geographia, chorography is the study of small parts of the world, as opposed to geography, which demands a more scientific surveying of larger tracts of land and nations. The root “choro” derives from the Greek word khoros, or place; whereas choreography is rooted in the Greek choreia, or circle dance. Two very different words, with quite distinct implications.

My misreading—a choreography of violence in Orleans Parish—might imply that the artist herself was organizing these deaths, an unlikely interpretation. But Luster, like any photographer, does construct her images—she researches and travels to locations around New Orleans in which murders took place and photographs them; she is obviously directing the viewer’s experience of these histories and places. However, my assumption was that the (erroneous) word “choreography” implied that others orchestrated the events she documented. In so many of her works the same locations recur as sites of violence, as though there were some coordination or planning at play. Indeed, some places in New Orleans are visited by murder with unnerving regularity, on two, three, or even four distinct occasions, the way dancers repeatedly hit their marks on the stage, every single night of the show. Choreography is about repetition, about composing gestures, about rehearsing and executing those movements in a repeatable way. Chorography is about place, about mapping at a small scale; Ptolemy believed it should be undertaken by draftsmen and artists, as they were better prepared to represent details of local experience.[i]

Not to dwell on that absent “e” too long, but murder in New Orleans, the subject of Luster’s book, intersects choreography and chorography, movement and place, intention and accident, repetition and trauma, in very specific ways. Looking at these violent events with hindsight, once you’ve seen the script of the inexorable finality of a death, these occurrences begin to feel depressingly practiced, predictable even. New Orleans has the highest murder rate in the United States (for over 20 years running), a rate ten times the national average, which also makes it the third most violent city in the world. Two thousand three hundred and twenty three individuals were murdered in the city in the years 2000 to 2010; in 2009, a year not uncharacteristic in terms of these statistics, 91.5% of those killed were black.[ii] Most murders in New Orleans take place in historically black areas like the 1st and 5th Districts, which include the neighborhoods of Treme, Mid-City, Faubourg Marigny, the 7th Ward, Bywater, the 9th Ward, and St. Roch.[iii] It is estimated that at least a quarter of the murder victims in New Orleans do not know their assailant; of these a great deal are casualties of seemingly random killings: drive-by shootings, botched robberies and muggings, or stray bullets. The victims were in the wrong place at the wrong time; unfortunately for many, the wrong place is their own neighborhood. In my misreading, my mental insertion of that little “e,” I believe I was thinking about these kinds of systemic repetitions.

From the book: Deborah Luster, Tooth for an Eye: A Chorography of Violence in Orleans Parish, 2011. Published by Twin Palms Publishers, Santa Fe.

Luster’s black-and-white images are round, shaped like peepholes or gun scopes. The circular format results from the particular lens she used in the project. Rather than framing the image to the square or rectangular format of the camera’s film, it offers a complete, uncropped image of the view through the lens. As the artist describes:

These prints are 49 inches high, by about 62 inches across… I have an old 8 x 10 Deardorff camera that I’d never used before and I had bought a lot of old lenses on eBay, so I started throwing all these lenses on this 8 x 10 camera and one of the lenses formed a perfect circle. It didn’t cover the entire film plane, so you see what the lens sees in its entirety, it’s surrounded by this little bit of fall-off called “the circle of confusion;” I don’t know, it images the city in a slightly different way, it does something to the grid, it reinforces the void. I thought “yes this is it” so these are all circles, all of these images.[iv]

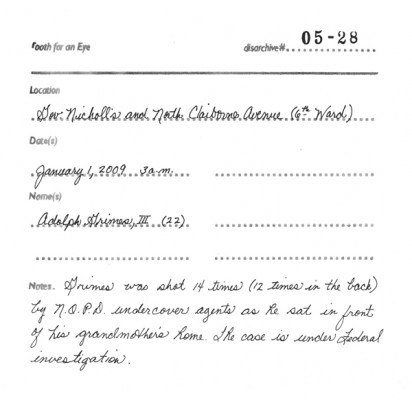

The images were taken in extended, 90-second exposures, resulting in a great deal of ghostly blur in the prints. Anything moved by wind, or traveling through the image, becomes spectral and indistinct. Given the charged nature of these sites, where blood has been spilled and lives taken, these phantom presences create visually complex surfaces that are simultaneously disconcerting and eerie. In one image, taken from the point of view of the victim’s parked car looking on to the murder scene, a large bush trembles with preternatural force. Buffeted by the wind, the shrub is captured in Luster’s photo as a large and angry presence. In this case, 22-year old Adolph Grimes III was shot by N.O.P.D. undercover agents early on New Years Day, 2009, as he sat in front of his grandmother’s house.

According to Luster’s deadpan textual commentary, “Grimes was shot 14 times (12 times in the back)… The case is under Federal investigation.”[v] This and other information about the crime is conveyed to the reader in Luster’s careful cursive handwriting, facing the image, as indeed is the case for each site she documents. Each record is brief but methodical, and employs the visual codes of the archive: a rubber stamp creates a template that names the project in its heading, and retains blank spaces for identifying facts such as the location, date, names of victims, and other notes. In these blanks Luster painstakingly outlines the essential details of the murders. In the upper right of each grid is a second stamp with two numbers separated by a dash, a private code of Luster’s project, filling in the enigmatically titled “disarchive” section.

From the book: Deborah Luster, Tooth for an Eye: A Chorography of Violence in Orleans Parish, 2011. Published by Twin Palms Publishers, Santa Fe.

I’m still hung up that little “e” I imagined in Luster’s title. Probably because language is so important to her project, and captions are essential. In this sense, Tooth for an Eye is particularly suited to a book format, in which information about the victims and murder sites faces the large, circular images of the crime scenes. Luster’s thoughtful essay is a fitting coda to this iteration of her project documenting 28 crime scenes, abbreviated as it is from the many she has documented.

But “chorography” isn’t the only puzzling aspect of Luster’s title that invites further consideration. “Tooth for an eye” is a deceptively familiar axiom, but Luster has transformed its original phrasing. She altered the “eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth” proverb found throughout the Bible into something more ambiguous and strange. The first occurrence of the saying is God’s command in Exodus 21:22-25:

If men fight and hurt a woman with child, so that she gives birth prematurely, yet no lasting harm follows, he shall surely be punished accordingly as the woman’s husband imposes on him; and he shall pay as the judges determine. But if any lasting harm follows, then you shall give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.

In the New Testament, in Matthew 5:38-40, a contradicting theological principle is put forward by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount:

You have heard that it was said, "An eye for an eye and a tooth for tooth." But I tell you not to resist an evil person. But whoever slaps you on your right cheek, turn the other to him also. If anyone wants to sue you and take away your tunic, let him have your cloak also.

The Old Testament usage is known as the juridical principle lex talionis, Latin for “law of retaliation,” which asserts that a punishment should equal the crime in severity. This retributive code of “like for like” is opposed by Jesus in his call for generosity in the face of violence—what others have called the ethic of Christian pacifism.

Luster transforms the saying into a third formulation—“a tooth for an eye.” One possible meaning of this revision could be that the crime should not exceed the punishment; that the already retaliatory notion of exact retribution should not become something more punitive. Yet a literal reading of Luster’s reformulation could be construed as contending that a punishment, though still retaliative, should be less harsh than the crime. We have more teeth than our more essential single pair of eyes, so a tooth for an eye would be a relatively lenient sentence (an eye for a tooth would be the more severe punishment).

But could it instead mean that her photography has bite, that it “has teeth”? That her acts of witnessing, sometimes long after the murders were perpetrated, produce an archive empowering new considerations of the role of violence in society, that may even galvanize viewers to action? Luster’s images picture an absent population, an absent public, one could say, of New Orleans. But she shows it to us, the living, those who can use her memorialization of erased lives, these often forgotten people, in order to rethink why this large, missing public continues to be taken before its time.

[i] In this sense Luster’s choice of “chorography” is interesting as an update of Situationist’s notion of psychogeography, a study of more subjective experiences of place than what maps offer.

[ii] http://www.city-data.com/crime/crime-New-Orleans-Louisiana.html. Stats taken from Charles Wellford, Brenda J. Bond, and Sean Goodison, “Crime in New Orleans: Analyzing Crime Trends and New Orleans’ Responses to Crime,” March 15, 2011, p. 12, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Accessed on April 26, 2011 from www.nola.com.

[iii] Wellford, Bond, and Goodison, “Crime in New Orleans,” p. 18.

[iv] “Tooth for an Eye: A Gallery Walk with Photographer Deborah Luster, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York,” February 1, 2011, www.kitchensisters.org/girlstories/tooth_for_an_eye/.

[v] Grimes comes up again in Luster’s book; it haunts her, one could say. Luster documents another police brutality case, in which 32-year old Kim Marie Groves was shot in the head on October 13, 1994. According to Luster, “N.O.P.D. Officer Len Davis ordered Paul “Cool” Hardy, a drug dealer, to murder Grimes in retaliation for her filing of a complaint of brutality against Davis and his partner.” Note Luster’s parapractic substitution of “Grimes” for “Groves.”