The Southern Half: Doris Ulmann at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Dillon Raborn considers how Doris Ulmann’s photographs at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art create a specific image of the South.

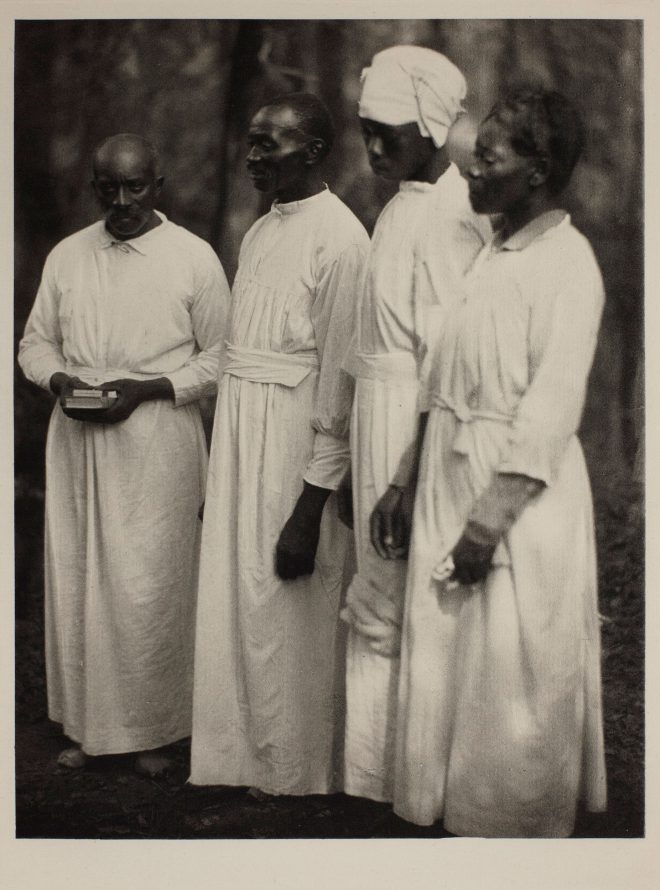

Doris Ulmann, Baptism – Group of 4, Roll Jordon Roll, 1930. Bromoil print. Collection of Joshua Mann Pailet.

The Ogden Museum of Southern Art is currently exhibiting the work of a New Yorker in the exhibition “Doris Ulmann: From the Highlands to the Lowlands.” Ulmann, a daughter to an upper-middle-class Reform Jewish family, practiced photography across the South in the early 20th century before her untimely death in 1934, barely over the age of 50. As a professional photographer, Ulmann’s portraits of celebrities like avant-garde dancer Martha Graham and physicist Albert Einstein appeared in a handful of reputable publications, most notably Vanity Fair, but her depictions of common Southerners, published in Roll, Jordan, Roll (1933), a collaboration with writer Julia Peterkin, and Allen H. Eaton’s Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (1937), are what earned her a place within the medium’s history.

Often noted as a pioneering documentary photographer, Ulmann is more properly understood as a proponent of the international Pictorialist style. The Ogden’s exhibition is quick to contrast her with the likes of Social Realist photographers including Walker Evans, Marion Post Wolcott, and August Sanders to emphasize the romantic tendencies she leaned into, evident in the characteristic softness in her work. Images of black churchgoers, rivers cutting through forested landscapes, and scenes of cemeteries beneath Spanish moss-covered branches suggest Ulmann was seeking a kind of storybook South with her bulky, tripod-mounted view camera.

The aforementioned publications serve as organizational parameters for much of the exhibition with prints displayed under their books’ titles. They do not, however, serve as strict limitations for content. For instance, selections from Handicrafts do not necessarily feature craftspeople or their products. The entirety of the show reveals the influence of the social progressivism of her day on Ulmann’s photography. She and others in her family were members of the New York Society of Ethical Culture—an organization founded by rabbi-in-training Samuel Adler on the principles of pursuing morality independent of religion, with an emphasis on helping the poor and the disenfranchised. This purpose comes out in the sympathy of Chaingang, Buckets, 1933, with its foregrounded field of stripe-suited convicts whose dark skin forms a syncopated composition against the pale sky. Most of them carry hoes, while one man front and center holds two metal buckets, his face downcast, his humble, brimmed hat shielding him from the day’s heat.

Doris Ulmann, Woman in Doorway with Peaked Hat, no date. Platinum-palladium print. Collection of Jessica Lange.

While Ulmann pulls heart strings in some photos, she skirts the line of exoticizing her subjects, and her photos can appear pandering or worse through a modern lens. Three portraits of Native Americans are grouped separately from the rest of the show. Among these is a 1934 platinum print of a rural family scene: A woman weaves a basket beneath a rickety shed covering plows behind her, while four toddlers lounge in the dirt, three of them strangely out of focus. The image feels explicitly sympathetic and is the sort of photograph that would have served Ulmann’s progressive agendas. But modern viewers will likely cringe at its title, Half Breed (Indian and Negro), South Carolina, and its racialized implications.

Freckle Faced Country Girl, c. 1934, is but one image that raises similar concerns with her relationship to her white subjects. The image of a young teenager in a somewhat antiquated summer frock leaning on a tree stump isn’t particularly compassionate, nor is the composition particularly picturesque. Ulmann was known to dress some of her subjects in outdated clothing to emphasize their existence within “primitive and pre-industrial” communities, to quote an article by Beverly W. Brannan for the Library of Congress. Ulmann’s ethical motivations aside, one should be suspicious of the work’s serving another purpose, namely portraying a young girl as an anachronism in order to hook the gaze of her audience. Relying on colonialist thought structures used to define the other as something unusual, Ulmann has filled that category with the figure of the rural Southerner.

It’s possible to give Ulmann the benefit of the doubt when it comes to such images, and she is certainly not the most egregious example among documentary photographers othering their subjects. She would have surely known of Jacob Riis’ famous How the Other Half Lives (1890), which, though it did inspire actual housing reform across the country, is tinged with exploitation. And while the publications that included her photographs undoubtedly served as documents of life in Gullah and Appalachian communities, there is still the suspicion that many of the rural Southerners in her work are indeed part of an “other half” of the United States foreign to most Northern city dwellers of the time.

Ulmann’s gaze and those of her audience and contemporaries, while perhaps well-intentioned, was far from perfect. Some of the more problematic of her works have been aired in “From the Highlands to the Lowlands,” and while the Ogden deserves credit for not shying away from them, the absence of added context stands out. Products of art history that have aged poorly, as some of Ulmann’s works have, deserve redress in the museum context, but a neutral perspective, however professional, isn’t always enough. In light of current conversations around equitable representation, unveiling problematic visions can and must be a course of action taken by curators—in their exhibition statements and wall texts—for contemporary viewers to grasp a fuller understanding of the past and its impacts on the present.

Editor's Note

“Doris Ulmann: From the Highlands to the Lowlands” is on view through September 16, 2018, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.