In Search of the City: Lee Friedlander at the New Orleans Museum of Art

Marjorie Rawle visits two Lee Friedlander exhibitions at the New Orleans Museum of Art and contemplates Roland Barthes’ writing about photography and loss.

Lee Friedlander, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1969. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

This spring in the New Orleans Museum of Art’s Great Hall, Lee Friedlander’s color photographs of some of the most iconic American musicians pulsated with energy. Intensely spotlit, their large scale and tight framing encapsulated both vigorous on-stage movements and intimate moments. Hung above eye-level, the works, which comprised the small show “American Musicians,” loomed over the viewer, diffusing the vibrancy of their subjects—Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Johnny Cash, Esther Phillips, Miles Davis. In “Lee Friedlander in Louisiana,” another exhibition now on view on the museum’s second floor, however, the photographer’s black-and-white body of work from the 1950s to the present speaks in a quieter voice, but one that is no less impactful.

While the musicians of the Great Hall are monumental and seem to be ready to burst from their frames, Friedlander’s images of Louisiana are noticeably sparser and shot at a wider angle. Bustling street scenes of parade revelry and ordinary commuters feel frozen and inanimate in ways that the “American Musicians” do not. Even the sprinkling of musician portraits contained in “Lee Friedlander in Louisiana” focus equally on the belongings and settings of their famous sitters like Aaron Neville and Louis Keppard as they do on their expressive visages. The contrast between the two exhibitions might be due to the fact that the “American Musicians” portraits were originally commissioned by record labels as promotional materials for the artists’ releases. The images were only later repurposed for fine-art prints. There is a sense, in both bodies of work, however, that some essence has been captured, whether it be of a performer or of a city’s culture; the difference is that in “Lee Friedlander in Louisiana” that essence is consistently obstructed and ultimately evocative of loss.

Perhaps because I am a young New Orleanian who will never know the city or the time depicted in the majority of Friedlander’s photographs on view or perhaps because there is indeed an inherent sadness in the medium of photography, as I walked through the four galleries of “Lee Friedlander in Louisiana,” I couldn’t help but think of Camera Lucida, literary theorist Roland Barthes’ last book published before his death in 1980. As one of the most prolific and incisive French intellectuals of the 20th century, known best for his work in Poststructuralist theory, Barthes took his many expectant colleagues and followers by surprise with this small volume dedicated entirely to photography. Camera Lucida poetically links taking and viewing photographs to a confrontation with time, love, and death.

Lee Friedlander, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1958. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Written while Barthes was still wading through the grief of losing his beloved mother Henriette Barthes, Camera Lucida proposes a hypothesis regarding the structure of photographs and offers a steady stream of intimate reflections and elegiac sentiments centered on a photograph of Henriette as a child. Barthes argues that a photograph contains two parts: the studium—the historically, culturally, politically, or symbolically recognizable elements in a photograph—and the punctum—a fundamentally indefinable and viewer-specific feature that “rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces [the viewer].” In Barthes’ framework, the punctum is almost always some seemingly insignificant detail of the composition, and it inexplicably becomes the vehicle through which the viewer experiences the “that-has-been” of the photograph—the jab of reality that indisputably proves the existence of the subject while simultaneously underscoring that same subject’s immovable place in the past.

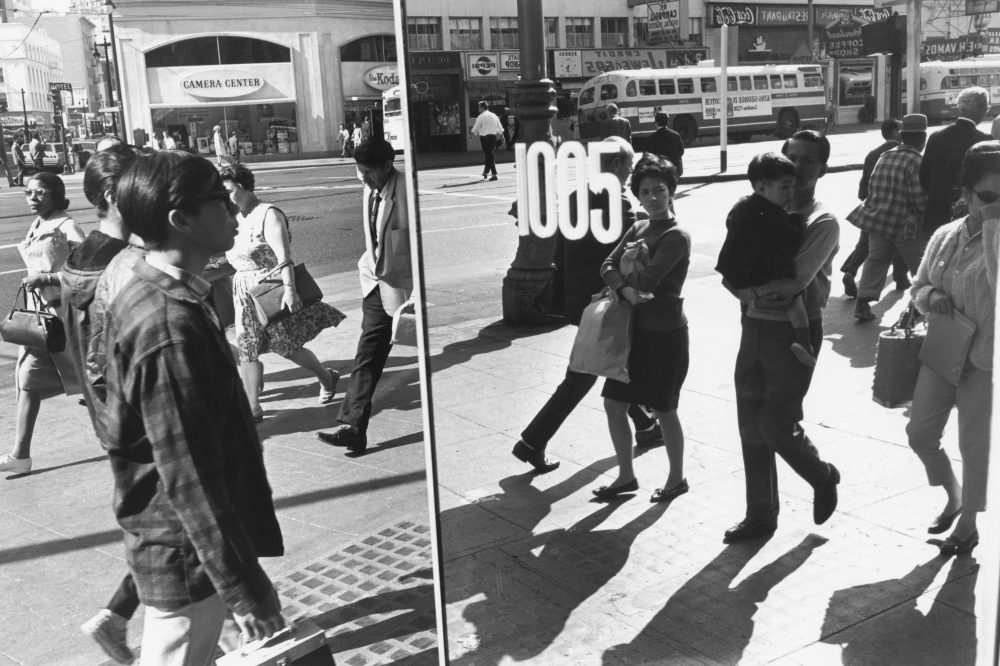

As NOMA’s wall text points out, Friedlander is best known for his attention to detail and optical illusions that compress and distort, rather than deepen, space in his photographs, calling attention to the medium of photography itself. These cues are hard to miss in images like one from 1970, in which two bespectacled women point their cameras toward the viewer as if waiting patiently for an obligatory smile, or in another photograph from 1967, wherein a sidewalk scene reflected in the mirrored windows of a building cleverly distracts the viewer from immediately noticing the photo store in the background.

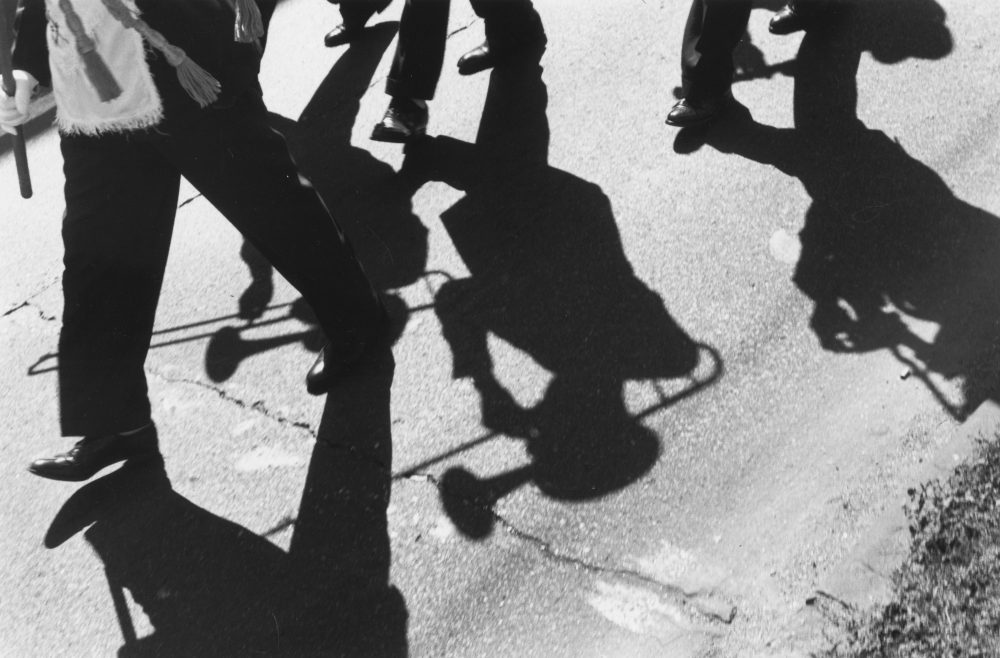

Yet, while overt optical plays and self-referential elements abound, there is something more, something that shifts in my mind when focusing on the dusty, finger-smudged window in a work from 1970, or on the snapping fingers of the blurred hand that abruptly juts in from the left of Second Liners, 1970. Details like these generate an unnerving sharpness, a pang that is most effectively described by Barthes’ concept of the punctum. For all its open-ended ambiguity, such a theory explains how the familiar subjects that take turns filling Friedlander’s frames—the New Orleans cityscape, street life, and musicians—remain so striking.

Lee Friedlander, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1967. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

In Camera Lucida, when Barthes finds the punctum and a sense of truth in the childhood portrait of his mother, he sorrowfully recognizes his “losing her twice over,” reminded by the photograph that she is no longer there. He is despondent, searching to explain an immense loss with photographic traces. For me, the ghost-like reflections and interruptions that lurk in a majority of Friedlander’s images similarly underscore the inaccessible past of a city that I call home.

In “Lee Friedlander in Louisiana,” transparent figures, buildings, and objects mix with solid ones, sometimes melding into an indivisible palimpsest, like the artist’s window-shopping scenarios, which blend reflections in glass with the objects in front of and behind it. These spectral details visualize the twinge of loss I felt subtly reverberating throughout the gallery—the desire for a place that I know was real, but that I will also never know since it no longer exists outside of images. It is not simply the fact that Friedlander depicts the Superdome under construction in 1973 or Mahalia Jackson strutting through the crowd of the first Jazz Fest in 1970, but it is also the consistent presence of shadows and photographs-within-photographs that remind me that time moves quickly and unforgivingly, leaving only murky traces of the past. This passing is felt particularly strongly in a city like New Orleans where deep-rooted traditions like Super Sunday and historic neighborhoods like the Faubourg Marigny and Tremé are subjected to the constant and sometimes noxious transformations of commercialization and supposed revitalization.

In his final paragraphs of Camera Lucida, Barthes writes that viewers have a choice: Photography can either be tame or mad—“tame if its realism remains relative, tempered by aesthetic or empirical habits (to leaf through a magazine at the hairdresser’s, the dentist’s); mad if this realism is absolute.” Instead of seeing the works in “Lee Friedlander in Louisiana” as formal exercises or even as a selection among innumerable, occasionally clichéd depictions of Louisiana and its culture, I couldn’t help but feel the madness of photography, the “intractable reality” of time passed and things lost.

Editor's Note

“Lee Friedlander in Louisiana” is on view through August 12, 2018, at the New Orleans Museum of Art (1 Collins C. Diboll Circle).