Critics’ Picks: “Constructing the Break” at the Contemporary Arts Center

Art Review contributors share some highlights from the Contemporary Art Center’s annual open-call exhibition.

Editor's Note

Each year on White Linen Night, the Contemporary Arts Center and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art help kick off the art season in New Orleans with their signature open-call exhibitions. The museums invite curators from outside their own institutions to select their picks from a pool of applicants, putting together their take on art in the area. Unlike traditional curated exhibitions, the works on view are selected only from those who apply, and oftentimes, juried shows are a great place for viewers to learn about established, mid-career, and emerging artists alike.

For “Constructing the Break” at the Contemporary Arts Center, Allison M. Glenn, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art—and Pelican Bomb contributor—chose 30 artists who live within 200 miles of New Orleans or who have shown work or held a residency in the area in the last calendar year. We asked a group of Art Review contributors to share highlights from their visits to the exhibition.

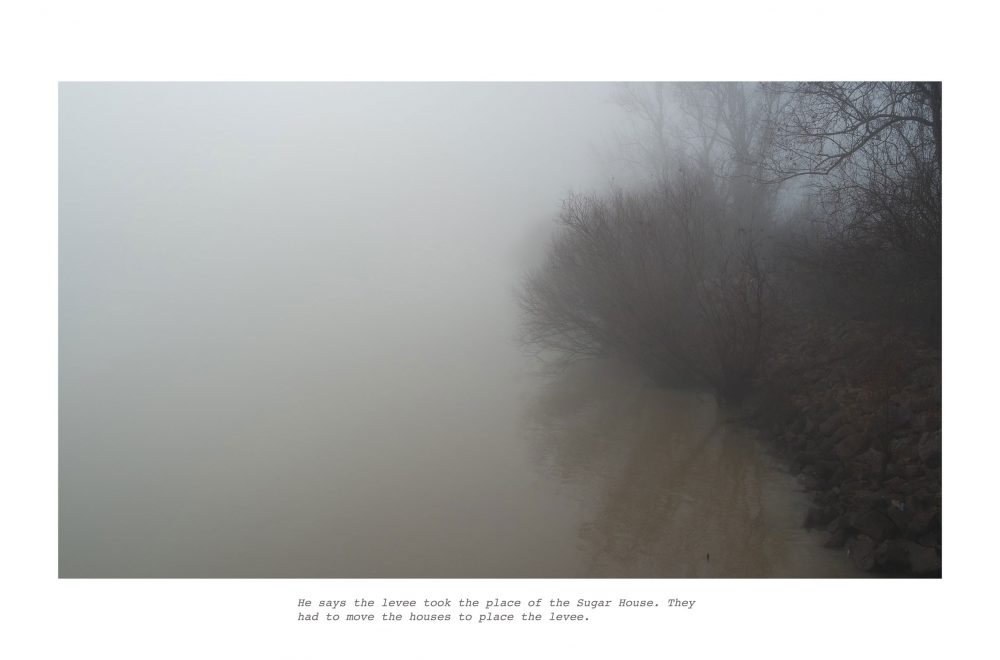

From Tia-Simone Gardner’s There’s Something in the Water: Yemoja and Osun, 2018. Archival inkjet print, velvet compass, digital and bodycam video, and audio capture of the Mississippi River. Courtesy the artist.

Tia Simone-Gardner

With There’s Something in the Water: Yemoja and Osun, 2018, Tia-Simone Gardner invites the viewer to reexamine a long, difficult relationship to the Mississippi River through her multimedia installation. A black velvet compass is framed by two hazy photographs that give haunting views of the river’s edge and a cloudy sky. Nearby, a video combines contemporary body-cam footage and sounds from the river with clips from a 1930s pro-New Deal documentary about the Mississippi. Gardner allows bits of the original film to speak for itself, while weaving her own perspective throughout. As the narrator tells a classic tale of “American resilience,” of the ways men attempted to control the river through levee infrastructure, and of the planters who “brought their blacks, their plows, and their cotton” to build commerce along the river, a caption notes that there are crucial perspectives left out of this narrative, namely, those of the black laborers who were exploited along the way. Yemoja and Osun are two feminine water deities in the Yoruba religion, which has long had its influences in New Orleans and other African diasporic communities. Gardner prompts viewers to wonder: What would Yemoja or Osun think of where society has come? Of where it’s going?

—Taylor Murrow

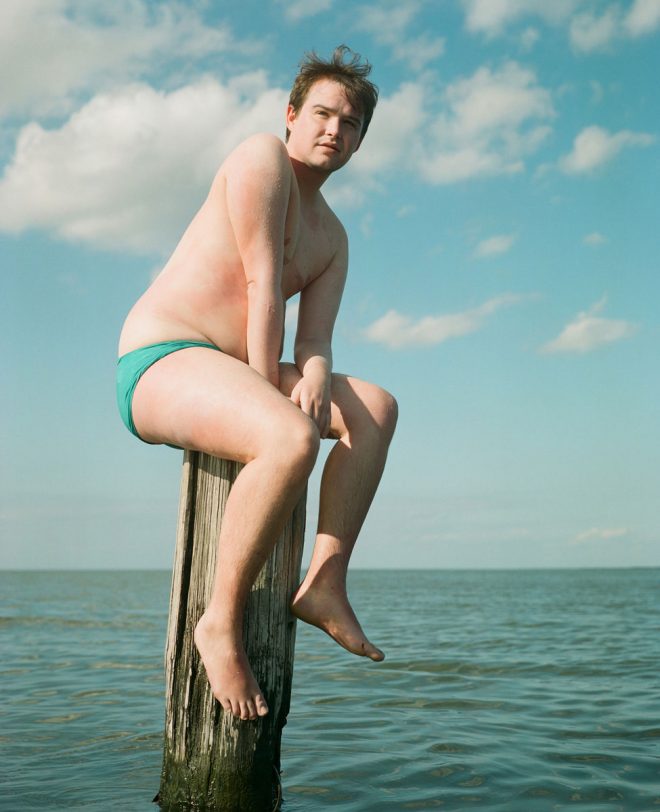

Chris Berntsen, Stephen on the Pillar, 2017. Digital C-Print. Courtesy the artist.

Chris Berntsen

Can you envision a queer utopia? I imagine it looks a lot like Chris Berntsen’s photographs.

His three portraits of friends and lovers in “Constructing the Break” are immediately marked by an intimacy between artist and subject strong enough to extend to the viewer, inviting us into those same lush green landscapes and crystalline expanses of water and sky that friends May, Baejing, and Stephen—who are named in Berntsen’s titles—occupy so completely. No other portraits in the show are as seductive or reveal their subjects being so fully themselves.

Of course, and sadly, utopias don’t exist: The word refers to both an imaginary perfect place and somewhere that by definition can never come to be. But Berntsen’s queer kinfolk are absolutely real and most emphatically present in his photographs. Confident but not theatrical in their physicality, they hold the promise of a better world.

—John d’Addario

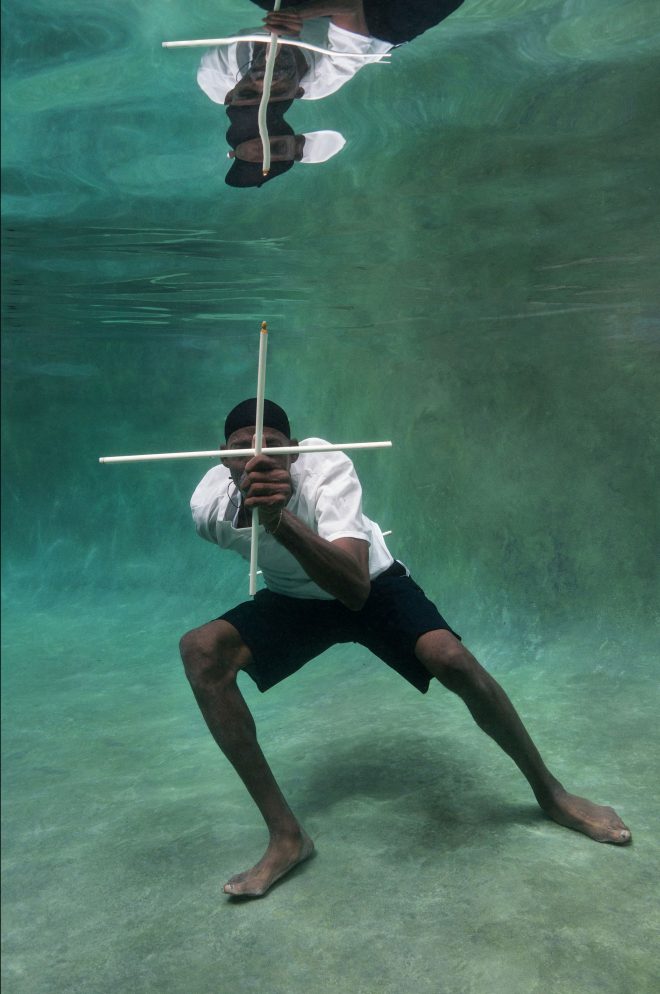

Michel Varisco, Crosshairs, 2017. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist and A Gallery for Fine Photography, New Orleans.

Michel Varisco

New Orleans’ relationship with water could be compared to that of infamous artist couple Marina Abramović and Ulay. While notably tumultuous, there might be no better pairing in the world when they are coexisting and performing together harmoniously. Despite being almost completely surrounded by water, New Orleans hasn’t been the most equitable partner, particularly in regards to educating herself about her partner’s idiosyncrasies. This lapse continues to show itself through water-system mismanagement in addition to failures to educate residents about many other aspects of their environmental wellbeing. Michel Varisco’s Crosshairs, 2017, explores this relational turbulence while proposing a more empathetic future between these two indomitable forces.

—Nic Brierre Aziz

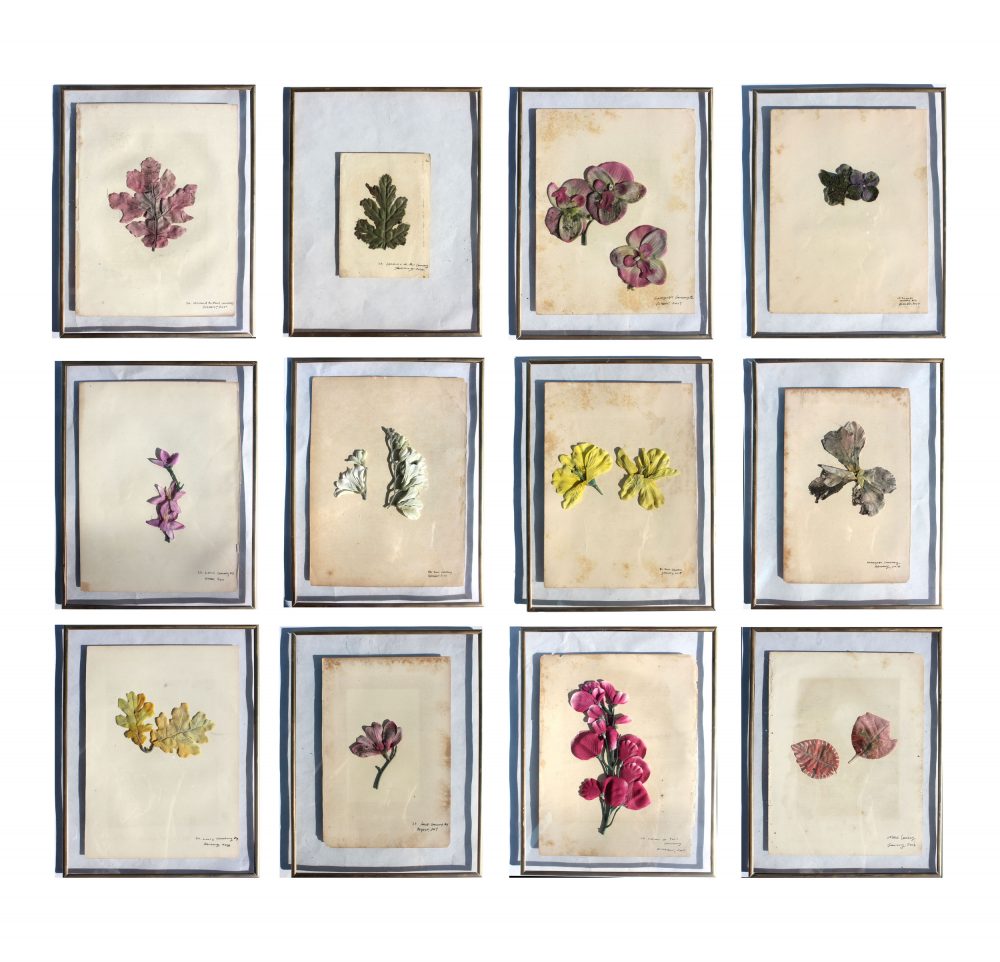

Rosalie Smith, I Want to Say “I Love You” Forever (1-12), 2017–18. Synthetic flowers collected from the drainage channels of New Orleans cemeteries, pressed in glass. Courtesy the artist.

Rosalie Smith

There is something simple, but not uncomplicated about Rosalie Smith’s flower pieces in I Want to Say “I Love You” Forever (1-12), 2017–18. The artist collected synthetic flowers from the drainage systems of New Orleans cemeteries, mounted them, and framed them—dirty, frayed petals and all—in the nostalgic style of real flowers carefully pressed and catalogued. The results are everlasting symbols of mourning and of the human desire for something to endure long after death. These flowers were tangled in catch basins, clogging the city’s sewerage system, which we depend on to prevent flooding. With New Orleans’ own longevity at stake, the poetry of Smith’s works is not lost.

—Taylor Murrow

L. Kasimu Harris, Poor Boys? (Vanishing Black Bars of New Orleans), 2018. Photograph. Courtesy the artist.

L. Kasimu Harris

Bars are undoubtedly one of the most loved, and notorious, aspects of New Orleans’ culture. In fact, 2015 research conducted by Trulia found that only three cities in the United States have more bars per capita. The ability to get a go cup and migrate through the city’s streets is often a feature that delights and perplexes many who visit the city—and enhances residents’ and visitors’ feelings of freedom.

But with drinking and socializing being so ingrained within the cultural fabric, bars can become sites of cultural contention. L. Kasimu Harris’ Poor Boys? (Vanishing Black Bars of New Orleans), 2018—part of a larger documentary series—illustrates conflicts of ownership and patronage as many of the “new and hip” bars that are now havens for New Orleans’ white transplants were once owned and frequented by the city’s African-American population. Unfortunately while these bars seek to be innocuous venues for joy and pleasure, many of them are complicit in the displacement of New Orleans’ longtime residents and culture bearers.

—Nic Brierre Aziz

Editor's Note

“Constructing the Break” is on view through October 6, 2018, at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans.

After your visit, head across the street to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art for “Louisiana Contemporary,” on view through November 4, 2018.