A Narrow Look: “One Place Understood” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

A recent exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art highlighted works from the Do Good Fund’s collection of photography from the American South. Nic Brierre Aziz considers the importance of representation.

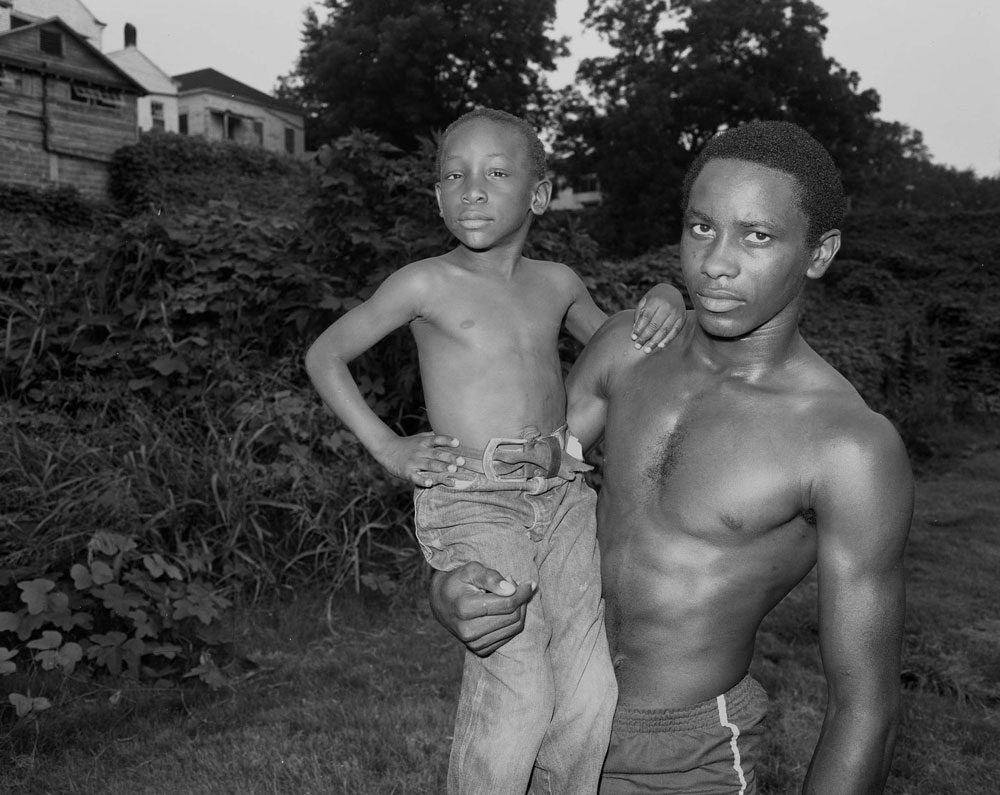

Baldwin Lee, Alan and Friend, Vicksburg, MS, 1983. Archival Pigment Print on Crane Museo Silver Rag Paper. Courtesy the artist.

The South has a tumultuous history, and its connections to slavery, racism, and inequality will unfortunately forever exist within its fabric. Past transgressions continue to float in the air of the area—through historically oppressive spaces, like the trees whose branches are sinfully familiar with African-American bodies or former plantation sites now home to a string of petrochemical plants known as “Cancer Alley.” As a result of these histories, any exhibition that takes on the goal of broadly addressing the South accepts a rather daunting task.

“One Place Understood: Photographs from the Do Good Fund Collection” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art took on this challenge with 43 different photographic works from the Do Good Fund collection. Since 2012, the Do Good Fund, based in Columbus, Georgia, has collected over 500 images taken in the American South since World War II, and the organization seeks to make its collection accessible through exhibitions and related programming.

Curated by Amy Miller, Executive Director of Atlanta Celebrates Photography, and Alan Rothschild, President and Founder of the Do Good Fund, the exhibition instantly captured viewers’ curiosity through the boldness and high quality of the images. While Jennifer Garza-Cuen’s Untitled - Girl With Snake, Rabun, GA, 2016, stood out as the most prominent piece in the first gallery, Baldwin Lee’s group of photographs nearby seemed to resonate more deeply with the intended scope of the exhibition. His Children Behind Screen Door, Rosedale, MS, 1986, and Alan and Friend, Vicksburg, MS, 1983, illustrate the nuanced Southern narratives—of religion, economic disparity, and race—referenced in the curatorial text.

These themes also came to life in works by Jill Frank and Gordon Parks. In Frank’s Couple on Dock, 2013, the photographer addresses a sense of heightened homophobia within the South by capturing a very sensual and intimate moment between a gay male couple. Frank’s Couple on Car, 2013, also exemplifies the beauty of finding love in spite of one’s surroundings, featuring an African-American couple sharing an even more carnal moment on the hood of a car. Unsurprisingly, Gordon Parks’ legendary documentary photographs were the exhibition’s most stunning and visceral. Just like Lee’s works, Parks’ speak directly to the complexities of stories of the South, depicting everyday life with both care and a critical eye.

Jill Frank, Couple on Dock, 2013. Archival inkjet print. Courtesy the artist.

In Parks’ Ondria Tanner and her Grandmother Window-Shopping, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, an African-American woman and her granddaughter gaze through a shop window into a sea of white-skinned mannequins. The piece seemingly illustrates psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s “doll test” of the 1940s—and it provides viewers with a poignant example of how early children are affected by inadequate representation and related racial inferiority complexes. Parks’ Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, touches on similar themes as six African-American children look through the chain-link fence of a park at a jovial white family on a playground with a merry-go-round and a Ferris wheel.

While Outside Looking In directly addressed the exhibition’s themes, it also ironically represented another reality. Of the 19 photographers featured in “One Place Understood,” only two of them were African-American—Gordon Parks and Eli Reed—and they happen to be two of the most notable African-American photographers of all time. The narratives of African-Americans, particularly in the South, have been underdiscussed and have often been told from the perspectives of others in power throughout the entire history of the United States, and the exhibition unfortunately perpetuates this paradox. In this context, Outside Looking In feels more like a conceptual portrayal of minority artists’ vantage points as they seek inclusion and representation—in the exhibition and in the contemporary art world at large.

The curators were obviously limited to the images in the Do Good Fund’s collection, but if the collection, which includes over 500 images, “ranges from works by more than a dozen Guggenheim fellows to images by less well-known, emerging photographers working in the region,” perhaps the organization should further expand its reach and break down fences so that the contemporary-art park can have a more diverse group of visitors.

Editor's Note

“One Place Understood: Photographs from the Do Good Fund Collection” was on view March 22–June 10, 2018, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.