Writing History: Maude Schuyler Clay at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Benjamin Morris looks at Maude Schuyler Clay’s portraits of her neighbors and friends in small-town Mississippi, prompting him to consider how history is written.

Maude Schuyler Clay, Lee, forsythia, 1994. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

Too often history is understood in terms of the grand narratives of our world: the conquest of land masses; the spread of ideologies; the pursuit or denial of freedoms. Less often, however, is history understood on the scale on which we experience it—that of the individual human. In “Mississippi History,” an exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art spanning twenty years of her work, photographer Maude Schuyler Clay seeks to reclaim that notion, offering an alternative to the idea of History with a capital “H.”

Clay’s photographs come largely from Sumner, a small town in the Mississippi Delta where her family has lived for five generations. As a portraitist, her style is unmistakable: Her images are direct and uncompromising, with her subjects nearly filling the frame, and her compositions frequently employ sharp angles and bold eye contact. Clay is renowned for her use of strong natural light, shooting at hours around sunrise and sunset when the light is so pronounced as to become a physical presence, offering stark clarity in one image, slicing bodies in half in another, or transforming the color palette in one more.

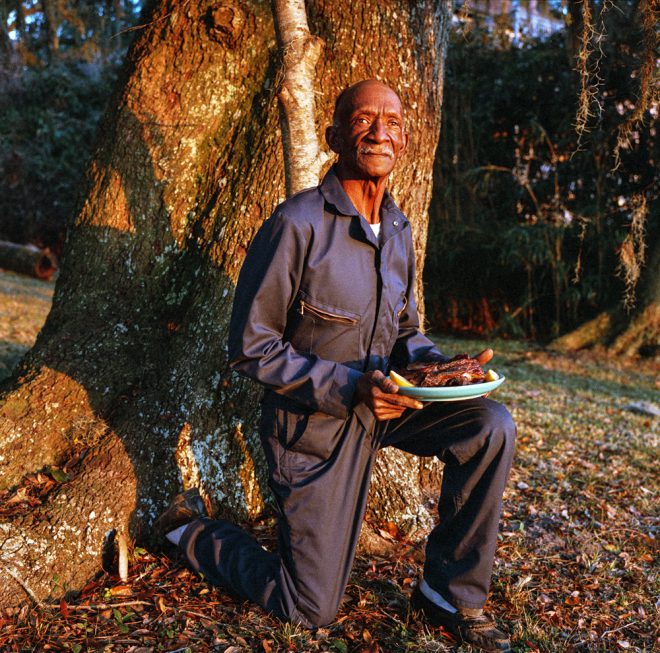

But technique and composition are only means to an end, and Clay’s primary interest is in people. “Mississippi History” introduces viewers to the citizens of Sumner with intimacy and grace, affording residents from all walks of life a rare dignity that other media might miss. Age, race, class, belief, or upbringing—Clay shows no special preference, wanting rather to chronicle anyone and everyone she sees, and it is clear in works such as MC’s barbeque, 1997, or Ann, Jasper’s funeral, 1992, that she is as familiar and comfortable with overalls and feed-store caps as she is tweed jackets and pearls.

Maude Schuyler Clay, MC’s barbecue, 1997. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

Indeed, this intimacy with the members of her community—her friends, her family, her neighbors—is a hallmark of Clay’s work and offers the richest and most rewarding experience for contemporary viewers. Certainly, for formalists, pleasures are easy to find, such as the many visual echoes that dot her pieces: In Tutwiler Boy with headdress, c. 1990s, an earring made out of a coin mimics the buttons of a jacket, or in Joan at Benton’s funeral, 1991, a pearl necklace brings to the fore the tiny orbs of yaupon berries behind the subject. Here, close observation is amply rewarded.

But relationships remain central. Hunting, bathing, posing, or peering out from behind the branch of a tree or shrub—a curious repeated trope—her subjects are fully alive, and we feel as though they are our neighbors, our family, our friends. And when they leave us—as in the images noted above, of Jasper’s and Benton’s funerals—we, too, remarkably, feel the loss. For Clay, the lesson is clear: The stories of the people right next to us, and of the beauty of their lives, may be the most important histories worth writing.

Editor's Note

“Maude Schuyler Clay: Mississippi History” is on view through January 15, 2017, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.