Where They At: Polo Silk at Antenna

Fari Nzinga visits Polo Silk’s current exhibition at Antenna, which presents the photographer’s documentation of bounce culture over the past three decades.

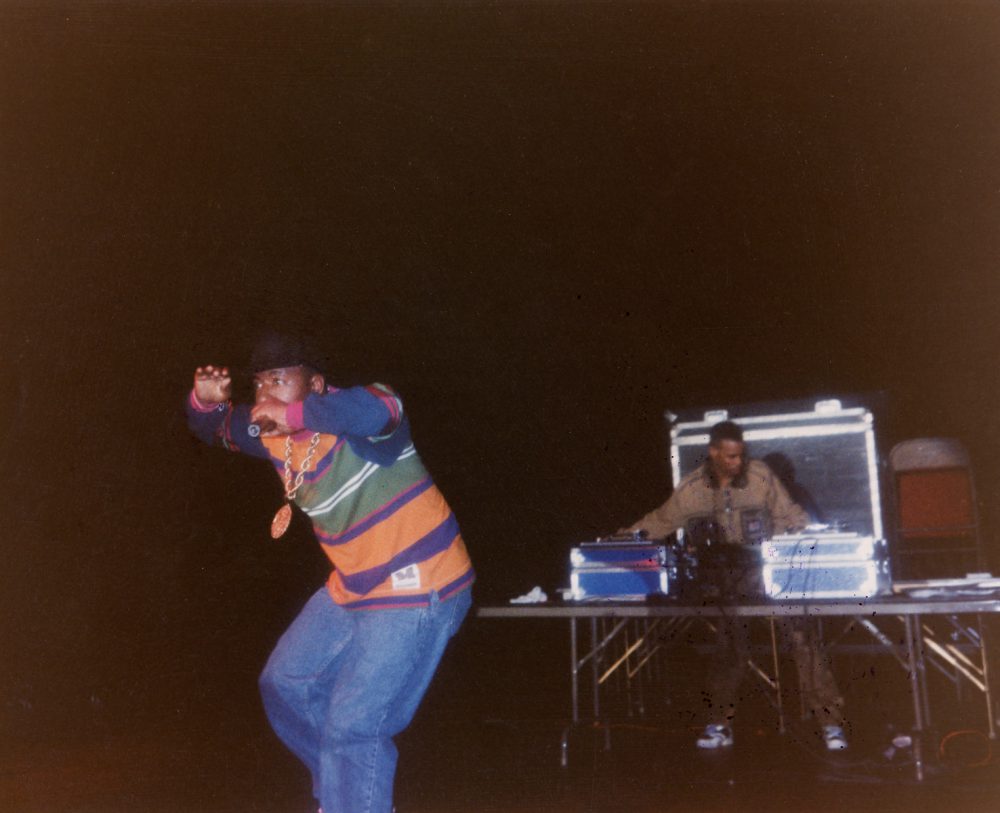

A photograph of MC T. Tucker and DJ Irv from Polo Silk’s “Pop That Thing” at Antenna, New Orleans. Courtesy the artist.

“Pop That Thang” at Antenna is largely comprised of photos taken by Sthaddeus “Polo Silk” Terrell at bounce clubs, hip-hop concerts, and other places in New Orleans where Black people gather, celebrate, and express themselves. In addition to photography from the last three decades, the exhibition includes flyers from bounce parties and rap concerts; a large, empty picture frame, reminiscent of a prop designed for an Instagram post, that guests can pose with; and two painted portraits of the man behind the camera—by artists Brandan “BMike” Odums and Charlie Wright—which gesture toward Silk’s stature in the community he chronicles. When I visited, exhibition curator Tammy Mercure exclaimed, “He’s an encyclopedia of like everything that happened Uptown.” His oeuvre is big, consisting of thousands of photographs as well as many handcrafted props and the airbrushed backdrops in front of which he takes pictures. The exhibition, containing about 200 photos and a handful of posters, shows how Silk has been creating and capturing Black cultural life since the late 1980s.

The exhibition offers a window into an aspect of local culture that is largely ignored in museums and galleries, as well as in the city’s tourism marketing. Upon first entering the second-story galleries, I was greeted by a playlist of New Orleans bounce classics: DJ Jimi’s 1992 anthem “Where They At” and DJ Jubilee’s “Get Ready, Ready,” among others. I found myself tryna twerk something as I lingered over the various walls of portraits depicting both performers and partygoers. As someone who was not born and raised in New Orleans, I was excited when I saw and recognized the faces of performers I know and love—to catch a glimpse of these artists before the professional hair and makeup, the slick PR and branding campaigns of hip-hop today. I was excited to see young artists whose music I loved in high school and college, like Mystikal and BG, and musicians like Vockah Redu, whom I’ve had the privilege of getting to know since moving to New Orleans. Seeing him on the wall made me feel like a real local. And there were many more whom I did not recognize. Wall labels might have helped some, though two slideshows include the names of local performers captured on stage, as well as the names of those whose faces grace the airbrushed tribute tees that are sometimes worn to simultaneously celebrate and mourn lost loved ones. These slideshows consist of Silk’s photographs projected onto the walls and looped, and some of these photos are also exhibited in print.

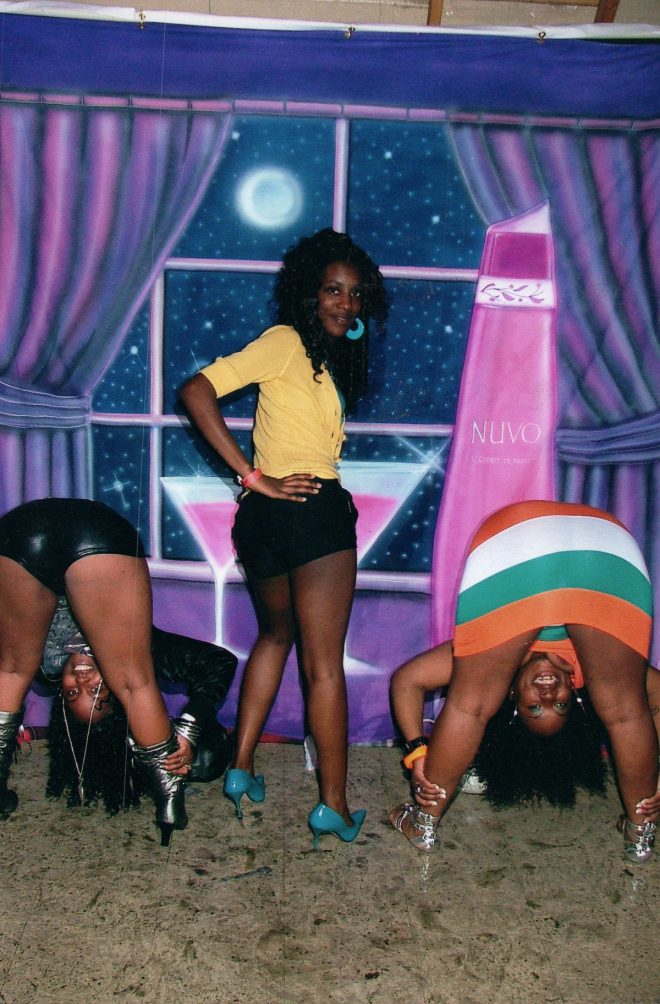

Taken at face value, the exhibition offers a look at evolving trends in fashion and music. Though some of the images are grainy or blurry, they point to stylized Afro-diasporic gestures similar to what French social theorist Pierre Bourdieu called “habitus”—the physical embodiment of one’s cultural capital, social standing, and worldview — and what art historian Robert Farris Thompson described as the “aesthetic of the cool”—women standing with hands on hip, men squatting down low to the camera. In one photo, a woman is doing a gymnastic split inside the club in front of a large green background. She’s wearing shorts and a polo shirt with Coach high-tops. In front of her, on the floor, is her matching Coach purse, a bottle of Heineken, and a bottle of Hennessy.

A photograph from Polo Silk’s “Pop That Thing” at Antenna, New Orleans. Courtesy the artist.

The lack of labels prompted me to look at the book designed to accompany the exhibition, wherein portraits of performers and artists are accompanied by memorable lyrics from their most popular songs. After perusing a few pages, I was finally able to put names and faces to some of my favorite bounce hits. And yet, I kept coming back to the fact that there is very little available in the gallery to help one interpret what is on display. I stayed for a while with that empty, handcrafted frame. Covered in camouflage felt and adorned with the words “Free BG”—dedicated to the Hot Boys rapper who was sentenced to 14 years in federal prison in 2012—its obvious Instagram appeal reminds the viewer of the ways in which bounce culture has grown and evolved with changing technology and the times; especially when viewed alongside the display box with the old Polaroid camera Silk once shot with. But without further contextualization, without a conversation with the artist himself, the frame’s use is unclear. Silk told me over the phone, “I take that ‘Free BG’ frame to second lines and have folks take photos with it and then I send the photos to him in prison to help keep his spirits up, so he knows that people haven’t forgotten about him.” These works have another life outside of the gallery and gain their value from the ways they circulate amongst individuals and communities.

There is one 8.5-by-11-inch sheet of paper hanging directly over this handcrafted frame, though the text and object are unrelated. An excerpt from venerable No Limit rapper Mia X, it explains some of the feelings of unrestrained freedom that accompany shaking and twerking to the beat. She writes, “We become one with the rhythm. Yes, it’s flattering when a crowd makes a circle around them to watch ladies pop that thing to the beat. But it’s deeper than sexual.” These words are a powerful reminder of Black women’s agency in a world where, when Black people are expressing themselves with white people present, their bodies tend to become objects of fascination, disgust, and desire.

And this brings me to the question of audience. In an article in the June/July 2017 issue of NYLON, Emma Bracy writes, “It’s kind of hard to talk about the current state of bounce without also talking about the current state of New Orleans in terms of gentrification and shifting demographics.” True that. From my conversation with Silk, the artist himself seems to be exhibiting for his 20-something nephew who wants to be a rapper; his elderly mother who used to think that p-poppin’ was the devil’s dance (but has since come around); his community, the people whose celebratory smiles and gestures fill the frames. But what about the venue’s art-world audience? For people like myself, who may not have a lot of knowledge of or expertise in bounce culture, what story does this exhibition tell? Maybe the story is that bounce music and the culture that it sprang from are finally being attributed the prestigious label of “art,” even as the city—with the displacement caused by escalating rents and new building developments—becomes more and more inhospitable to the culture bearers themselves.

Editor's Note

Polo Silk’s “Pop That Thing” is on view through September 3, 2017, at Antenna (3718 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.