The Importance of Context: “Inner Journeys” at the New Orleans Museum of Art

Marjorie Rawle examines how an exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art attempts to draw connections between the paintings of New Orleans-based artist Regina Scully and Edo-period Japanese landscapes.

Regina Scully, Origin of Dreams, 2017. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

To an auditorium full of horrified museum-professionals-in-training, one of my favorite art-history professors from college once insisted that wall text for art exhibitions are habitually overused, long-winded, jargon-ridden, and ultimately superfluous—and that they should be eradicated. But to my mind (and I think most museum-goers, at least those who aren’t walking encyclopedias, would agree), labels and other supplementary materials often elucidate critical, curatorial, and art historical concepts that might otherwise go unnoticed or be misunderstood.

My professor would be scandalized to hear this from me, but “Regina Scully | Japanese Landscape: Inner Journeys,” on view now at the New Orleans Museum of Art, could really use more text. The exhibition’s underlying mission is a compelling one: to inspire a close inspection and fresh discussion of two seemingly disparate topics—contemporary abstract painting by a New Orleans-based artist and Edo-period Japanese landscapes—using visual and conceptual links to form an effective springboard for joint exploration. In practice, though, the effort translates less as the dialogue across time, culture, and genre that it purports to be, and more as a solo show that has failed to notice that it isn’t, by definition, a solo show.

According to the brief exhibition text on the gallery’s walls, Regina Scully’s work, with its expressive lines, careful coloration, and dynamic compositions, has always had an “intuitive connection to Asian Art,” but, as another short blurb on the museum’s website puts it, with “Asian art exert[ing] no direct influence on Scully’s practice.” NOMA’s Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs and Curator of Asian Art Lisa Rotondo-McCord recognized these somewhat vague commonalities of form (“strong, calligraphic line, distorted perspectives, hybridized forms, compressed spatial relationships and frequent use of black ink and fluid brushwork”) and, over the course of the last year, brought Scully behind the scenes at NOMA for the artist’s first in-depth look at a variety of Japanese paintings—in particular Nanga, or literati paintings—in the museum’s collection. In response, Scully created seven vibrant paintings that incorporate Nanga-inspired elements such as long, fluid brushstrokes and an expanded sense of space. Whereas Scully’s earlier works, especially the monochromatic Navigation series from 2010, also included in the exhibition, are made dense and angular with myriad short, straight marks, her new paintings, like Mindscape I, 2017, softly undulate with expansive stretches of vibrant color and a newly sinuous range of mark-making, characteristics also found in the Nanga hanging scrolls on view.

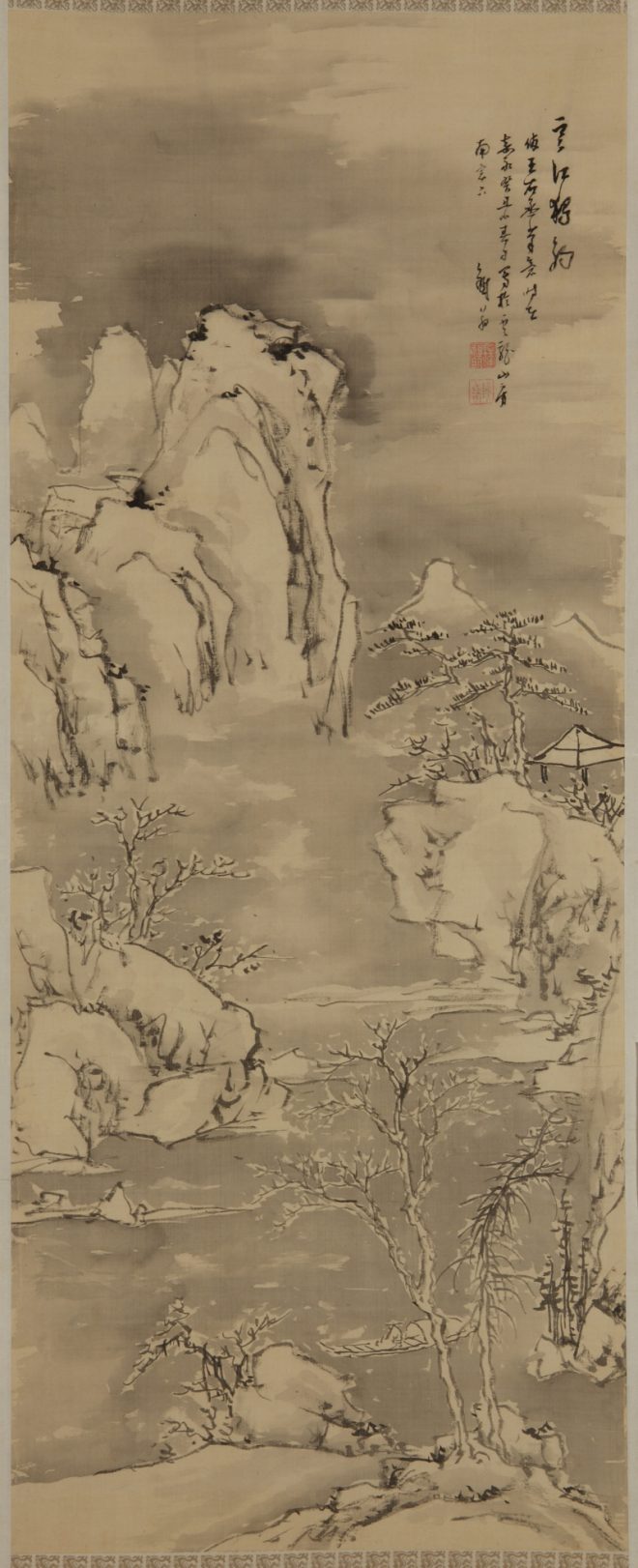

Sō Aiseki, Shadows of the Setting Sun, not dated. Ink and color on paper. Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

These paintings, and a selection of Scully’s other works from various points in her career are woven throughout the museum’s permanent-collection installation of Japanese art, which includes a spread of 17th- through 19th-century hanging scrolls as well as a few albums of smaller ink paintings on silk by notable Edo-period artists like Ike Taiga and Nakabayashi Chikkei. This intermingling is strategic and shrewdly avoids tempting the viewer to make one-on-one comparisons by placing groups of Scully’s works adjacent to or facing groupings of Japanese works. Instead viewers are encouraged to wander in and out of the two bodies of work continuously to make note of both pronounced and subtle formal connections, but the question inevitably becomes: to what end?

Presenting Scully’s work alongside the Japanese paintings she studied makes for a vastly more interesting exhibition idea than a run-of-the-mill solo show, and, as a visitor, it was at first rewarding to visually zigzag throughout the space, drawing three-centuries-long parallels between mark-making, composition, and color usage. I am not so sure, however, that the exhibition allows for an equally deepened understanding of both Scully’s paintings and Edo-period landscapes, or that it creates a true “dialogue” between the two, as the exhibition’s affiliated texts assert. With almost no contextualization beyond a three-sentence paragraph in a printed brochure available in the galleries and without a single image worked into the design of this booklet, the Japanese paintings on view feel flattened into mere reference material, significant only in their visual similarity and nebulous conceptual link to Scully’s work. The more my eyes wandered through the hazy mountains of Takahashi Sohei’s Mountains in Mist and Trees and Clouds, 1832, and quiet pathways of Takaku Aigai’s Summer Landscape, 1836, the more I realized that substantive information on the literati tradition, its artists, and its larger historical context was not available to me anywhere in the exhibition, which as a result adds little to any discussion of Nanga as a significant art historical tradition in its own right. This omission and blatant lean toward a contemporary painter prompts larger questions about the inclusivity of Western art history and how the canon—defined and communicated to us largely by way of public institutions like art museums—determines which artists and which works are central to our collective discourse around art, and which are not.

Perhaps a more thorough explanation of the social, political, and artistic climate of Edo-period Japan might add clarity to a curatorial direction that urges us to take—in Rotondo-McCord’s words—“imagined and imaginary journeys” and asks the viewer to engage more deeply with both Scully’s painting and NOMA’s permanent collection. For instance, as contemporary viewers, we are constantly briefed on and abreast of the societal turmoil from which Scully’s work provides “visual escape,” giving her paintings automatic layers of meaning for us; not so obvious, however, are the “political and societal constraints” to which the Edo-period artists are responding, which to me feels like a missed opportunity for an engaging cross-cultural comparison that moves beyond the purely visual. In its current state, with its uneven tilt toward Scully and her practice’s benefit from her recent investigation of Japanese art, the framing of the exhibition effectively removes one half of the dialogue—the museum’s calls for a novel and open exploration ringing empty.

Editor's Note

“Regina Scully | Japanese Landscape: Inner Journeys” is on view through October 8, 2017, at the New Orleans Museum of Art (1 Collins C. Diboll Circle).