Serious Times: “Alien vs. Predator” at the New Orleans Art Center

Fari Nzinga visits a recent show at the New Orleans Art Center that questions who is the predator and who is the prey in today’s America.

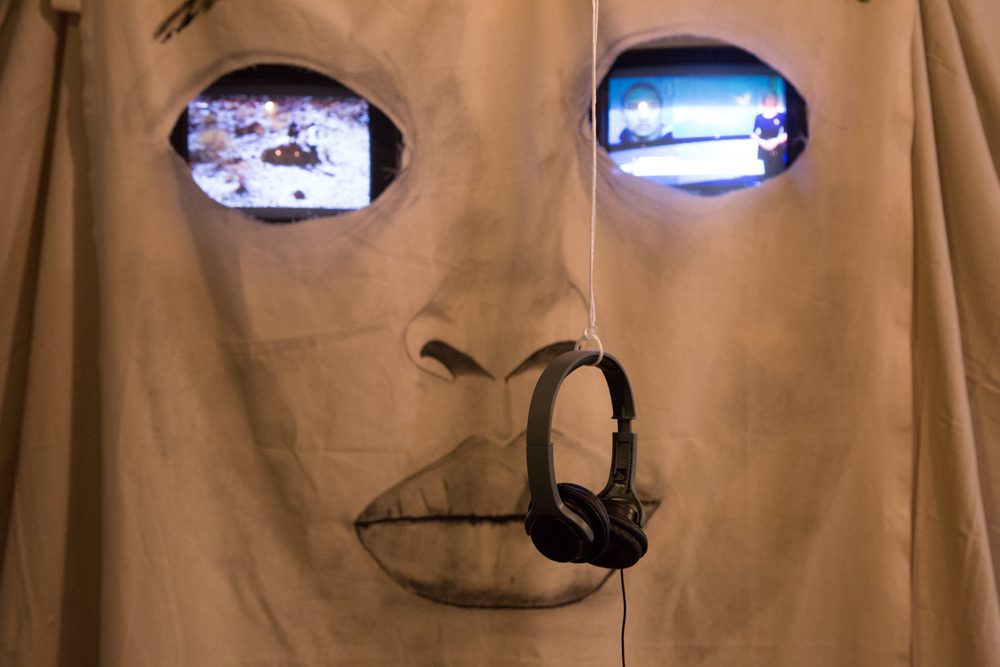

Nathan Edwards, Who Do You See?, 2017. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Zuri Obi-Louis.

With 26 artists represented in the recent exhibition “Alien vs. Predator” at the New Orleans Art Center, there was a lot to see. Displayed in a large, raw gallery space, the artworks mostly consisted of mixed-media pieces and installations, while photography, painting, and textile art rounded out the collection. The exhibition was conceived by curator Nicolas B. Aziz in response to the criminalization and mass incarceration of Black and Latino populations in the United States. Taking the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994—the largest crime-control bill in American history, which provided funds to hire 100,000 police officers and $9.7 billion for prisons—as its point of departure, the artists in “Alien vs. Predator” question who is the predator and who is the prey in today’s America.

Upon entering the space, I was greeted by Glenn Ligon-esque neon lights of the words “We hold these truths to be SELF EVIDENT” by artist Ti-Rock Moore. The lights are displayed on a freestanding, removable wall, the other side of which is the backdrop for Nathan Edwards’ mixed-media installation Who Do You See?, 2017, which is made up in part by an oversized white canvas sheet hanging from the ceiling with facial features drawn in charcoal. Behind the cut-out eyeholes are two television monitors. On the left, the screen displays personal footage taken by the artist of friends and himself traveling, laughing, and graduating from college. On the right, the screen shows images taken from the news portraying Black men as criminals, defendants in court, and the like. Suspended from the ceiling in front of the face and monitors is a pair of headphones playing Kendrick Lamar’s song “FEAR.” off his latest album DAMN. Edwards’ installation emphasizes the duality of representation and convincingly calls attention to W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of double consciousness, or the awareness, particularly for African Americans, of oneself both on one’s own terms and as viewed and characterized by outside antagonists.

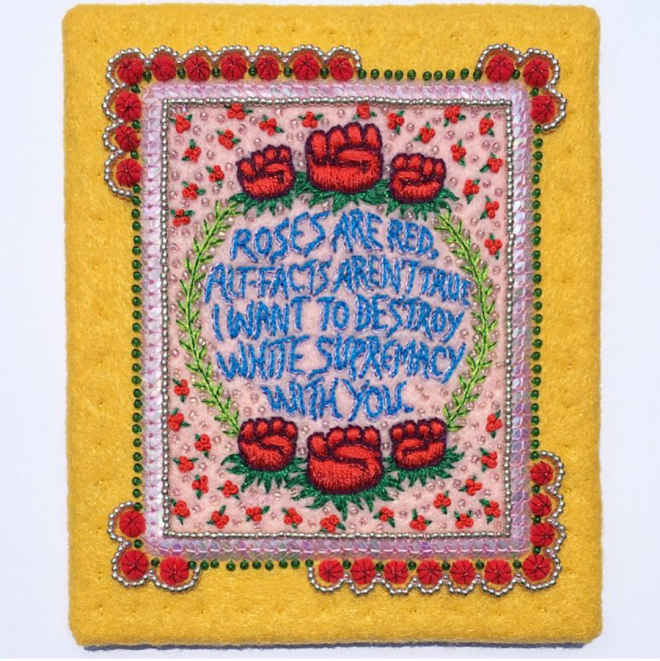

On a smaller and more intimate level, artist Kate Madeira’s Valentines for Serious Times 3, 2017, is a small rectangle of felt, hand-embellished with beads. It reads “roses are red, alt-facts aren’t true/I want to fight white supremacy with you”—a gesture toward the emotional labor involved with relationship, movement, and coalition building and the tenderness and care with which dissidents and oppressed groups must treat each other in order to survive and thrive in the contemporary political and economic climate.

Kate Madeira, Valentines for Serious Times 3, 2017. Courtesy the artist.

The gallery space is punctuated sonically with the cries and refrains of actress Esther Rolle. Carl Joe Williams’ Irony of a Black Policeman, 2016, features an old television overlaid with colorful geometric patterns. Sprouting out of the top of the sculpture appears to be a sort of miniature scaffolding of plastic tubes holding a statuette of Jesus in white flowing robes. On the screen, under the colorful print, is a video on loop that splices scenes from Good Times with contemporary news snippets about police murdering Black people. In one scene from the TV sitcom, a distraught Rolle eerily shouts into the telephone, “You just find him!”

Adjacent to Williams’ installation, in the middle of the floor in the gallery space—its physical center, but also, Aziz tells me, the thematic center of the exhibition—is a sculptural work by Lorna Williams (of no relation to Carl Joe): a dead tree without branches, punctuated with holes lined with little copper rings and surrounded with shell casings instead of soil. It’s an interactive piece, Aziz notes as he grabs the tree and cranks it in a circle. Spinning the tree represents imbuing something dead with new energy and life, while the bullets are there to symbolize resiliency in the face of violence and death.

Aziz tells me that he chose the title of the exhibition as an unambiguous take on a contemporary obsession with competition and violence, while also a scathing commentary on the fact that the term “super-predator,” made famous under Bill Clinton’s administration, spread like wildfire through pop culture and the media. When I was doing a walk-through of the exhibition with Aziz, another gallerygoer, Shannelle Mills, pointed out that both “alien” and “predator” are words tinged with racial animus and hurled at Latinos and Black people, who are often forced to compete for access, status, and resources under white supremacy.

Because there were so many artworks to see and interpret, the exhibition felt like it needed an editing eye, as some artists seem to have gotten lost in the crowd. While the theme was clear, the ways in which certain works related to one another was less so, and the large number of artists all working in different media hindered the potential for cohesion, power, and impact. But ultimately, the exhibition fulfills its goals to get visitors talking and thinking about the ways in which Black and Latino communities have been oppressed and exploited for political and economic gain. If you went in with an appetite for rigor and reflection, there was certainly food for thought.

Editor's Note

“Alien vs. Predator” was on view August 12–September 3, 2017, at the New Orleans Art Center (3330 St. Claude Avenue).