On His Trail: Jacob Dwyer’s “DAT LIKWID LAND”

Benjamin Morris watches Jacob Dwyer’s recent film, which the artist shot during a residency in New Orleans with Deltaworkers.

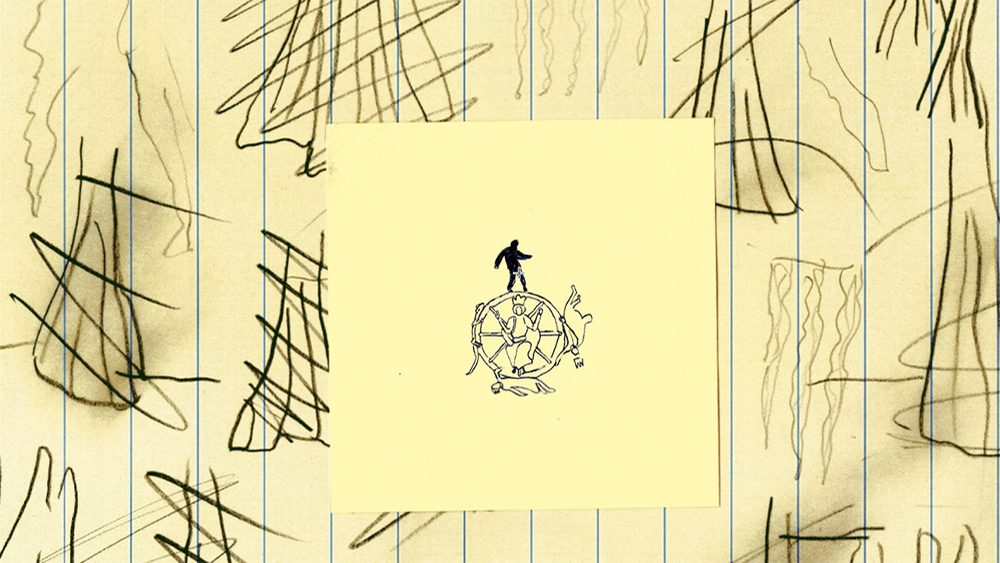

A still from artist Jacob Dwyer’s DAT LIKWID LAND (2017). Courtesy the artist.

A mystery story, featuring enigmatic lost artifacts. A documentary, exploring the life of a tragic figure. An homage to a beloved novel, whose presence still looms large over New Orleans. A film that is at once captivating, curious, frustrating, and haunting, Jacob Dwyer’s new, roughly 30-minute work DAT LIKWID LAND (2017) occupies multiple genres at the same time, crossing lines as easily as his characters cross streets.

Shot primarily on location here in the city and in southeastern Louisiana, DAT LIKWID LAND follows an unnamed narrator (voiced, but never embodied, by Dwyer) who stumbles upon a mysterious notebook of unknown origin in a local bus station. Seemingly abandoned by its owner, one Ignatius J. Reilly, the notebook contains a host of arcane sketches and ramblings, including cosmic diagrams of Fortuna with her wheel and screeds on the inanity and absurdity of everyday life. Intrigued, the narrator sets out on a quest to find Reilly, and over time, by investigating the manuscript, by visiting key sites, and by interviewing a slew of eccentric locals, comes to realize that Reilly is but a character created by another man, a novelist, one John Kennedy Toole.

For anyone with a basic knowledge of Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces—widely regarded as one of the great novels of this city—this reveal was signaled well in advance. Signature emblems of the book—Reilly’s hunting cap, references to a garment factory (aka Levy Pants), and an unmistakable reference to Lucky Dogs—signal who Dwyer’s narrator is pursuing, even if he remains in the dark for much of the film. Once the truth dawns, though, the search for one mysterious individual simply evolves into the search for another, who may prove even more elusive than his creation. After all, one of the great—and tragic—questions of modern literary history is just why Toole decided to end his life so young, rather than continue to seek publication for such a magnificent book.

A still from artist Jacob Dwyer’s DAT LIKWID LAND (2017). Courtesy the artist.

Amid Dwyer’s encounters with locals, much of the film consists of explorations of southern Louisiana, with sojourns both through the urban landscape of New Orleans and the wetlands of the coast. And it is here, by skirting the iconic spaces of the area, that his cinematography stands out, preferring to suggest rather than to sell, and to ask rather than answer. While Dwyer does employ brief shots of the French Quarter and the Mississippi River, he is more interested to explore more distant areas such as Wilson Avenue in New Orleans East, or more rarefied spaces such as the Special Collections archive at Tulane University—hardly a tourist destination. Innovative framing from multiple perspectives (e.g. square-format screen grabs from a computer), vividly saturated coloration, and long tracking shots add an inventiveness and playfulness to the search, while anonymous personae and portentous camera work add a touch of ominousness—as in films by David Lynch or Chris Marker, where, with each new clue unearthed, the mystery only grows deeper.

At such a short length, in some ways it feels the film ends before it truly begins, and many of the questions Dwyer asks remain unanswered. But ultimately, at the heart of DAT LIKWID LAND is an exploration not of the confines of a place, but of the boundary between truth and fiction, and as the film reaches its denouement, that line becomes increasingly smudged. Once it becomes apparent that Toole, not Reilly, is the true subject of the search, this new truth ruptures the narration in ways that become uncomfortable not just for the narrator but for the viewer as well. Indeed, it is here that the film stumbles in handling its source material, when Dwyer interviews artist Elizabeth Shannon, who in real life had been one of Toole’s students in the 1970s. The problem arises when nearly every insight or recollection Shannon disclosed about Toole remains off-screen—even as Dwyer the narrator ostensibly conducts a formal interview, Dwyer the filmmaker leaves it all on the cutting room floor. For viewers eager to learn more about this enigmatic novelist (about whom sources can be limited), this segment of the film comes across as nothing more than a tease—simultaneously frustrating viewers’ desires for knowledge and failing to advance his own narrative.

A still from artist Jacob Dwyer’s DAT LIKWID LAND (2017). Courtesy the artist.

To be fair, maintaining a strict boundary between what is real and what is fictional was never the aim of DAT LIKWID LAND. Indeed, such a stance finds its clearest expression in the closing scenes, which depict Dwyer’s narrator departing New Orleans via one of its many cemeteries. As he passes by, he encounters a strange figure, dressed all in black, dancing on top of a mausoleum—wordless, independent, joyful, and very much alive, the scene is startling both for how unexpected it is and for how unexplained it remains. This figure appears in Reilly’s notebook at the beginning of the film only as a sketch, so to see it realized so viscerally comes as nothing less than a shock. Nor does the film answer whether the notebook had inspired the dancer, whether the dancer had been complicit in writing the notebook, or whether there is any discernible relationship between them at all—offering instead only a living enigma, whose lips are firmly sealed.

In this respect, by the end of the film, the search for the boundary between truth and fiction turns out not to be misguided or even naïve, but merely obsolete. Ultimately, according to DAT LIKWID LAND, the relationship between an author, characters, and the world around them can never be fully circumscribed—as, in some way, it should be.

Editor's Note

Jacob Dwyer was a Deltaworkers artist in residence in 2015. Watch the trailer for DAT LIKWID LAND on Vimeo.