Shadow Histories: “Solidary & Solitary” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

At the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Benjamin Morris visits an exhibition that outlines a historical lineage of black artists.

Sam Gilliam, After Glow, 1972. Acrylic and dye pigments on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

For every history that is told, there are other ones that are whispered. For many students of 20th-century art, Modernism and abstraction are defined by painters such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko. Yet as the new exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art demonstrates, working right alongside those household names (and, in some cases, prior to them) were black artists whose works have occupied a kind of shadow history that this show foregrounds in compelling ways.

The works in “Solidary & Solitary: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection,” on view at the museum until January, span over 70 years, beginning chronologically with Norman Lewis and ending with contemporary artists such as Mark Bradford, Leonardo Drew, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The works are drawn from one of the largest private collections in the country of Modern and contemporary works by artists from the African diaspora, and following their stay in New Orleans, will be traveling to (among other places) North Carolina, Indiana, and Maryland. (Last year, a volume of essays on the collection was published.)

Organized around the idea of solos and duets—artists working in isolation, the “solitary,” and artists responding to the works and legacies of others, the “solidary”—the show explores the rewards of both experiences. For black artists such as Lewis and Sam Gilliam, whose works were at different times shunned by artistic establishments, such rejection spurred them on to greater experimentation and formal innovation, yielding such powerful works as Gilliam’s Stand, 1973, or Streak of Lightning, 1986, which not only break the traditional rectangular plane of the canvas but also marry this breakage to bold, expressive gestures in color and texture. In Gilliam’s Reading Across, 1994, for instance, discrete raised panels are rent by thick textures and swipes of paint, amid a spare, smoky palette whose mood is enlivened by slashes of scarlet. The visual effect is mesmerizing: carefully controlled and expressive all at once.

Melvin Edwards, Central Ave. LA, 1991. Welded steel. Courtesy the artist and Artists Rights Society, New York.

That tension is developed elsewhere in the show, in works by Drew and Melvin Edwards. Drew’s recent Number series, large-scale works composed primarily of wood, offer spectacular intrusions into space that progress from regular, minute gradations into unruly, beautiful explosions. In Number 52S, 2015, wood panels that have been hewn, sanded, and painted a uniform black gradually give way to the outgrowth of whitening planks that eventually become actual tree roots, breaking all boundaries of geometry and showcasing the ethereal beauty of the untamed. Nearby, Number 185, 2016, echoes the gesture, but begins with an even more restrictive form: a precise mathematical grid in its lower-left corner, from which the rest of the forms then flow.

The dialogue between Drew and Edwards becomes apparent when looking at Edwards’ Lynch Fragments, a decades-long series of metal implements such as hammers, machetes, and saws that have been twisted and welded into compact condensations of themselves, such as in Central Ave., LA, 1991, or Centuries, 1993. Edwards made these works after the slaying of a Muslim African-American man in Los Angeles, and their power comes in how compressed they are, how tightly wound, like a fist or a curse. Bodies of tortured metal made out of metals that have tortured human bodies—it is impossible not to feel Edwards’ grief, a furious lament forged directly into cold steel.

Other works in the show offer novel visual forms, such as Charles Gaines’ Numbers and Trees, Central Park, Series 1, Tree #9, 2016, which recasts the figure of a tree into minutely-organized pixels, each color-coded in order to reveal the many parts that make up a single organism, challenging our modes of perception and apprehension. In a side room, Jack Whitten’s Omikron 1, 1977, offers the illusion of depth and texture on a flat canvas, and Mark Bradford’s large-scale No Time to Expand the Sea, 2014, transforms humble artifacts of everyday print culture from Los Angeles—such as handbills, advertisements, and newspapers—into forms that evoke the beauty of shattered glass, rearranged from an original image into something altogether more mysterious. Such approach to the ineffable is found as well in Jennie C. Jones’ quiet, minimalist renderings of piano keys and sound boards (Composition for Sharps #4, #5, and #6, all 2010), which by mimicking musical notation on their frame evoke the sounds that could have been made but which remain in perpetual silence—an invitation not simply to irony but to imagination.

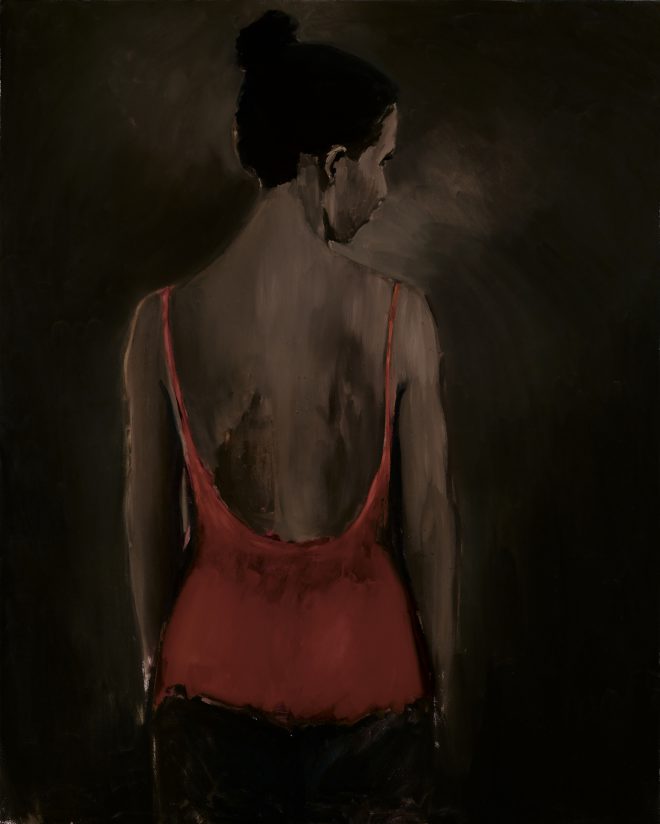

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Places to Love For, 2013. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist; Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; and Corvi-Mora, London.

Subtle as such gestures are, it is ultimately in those works that directly engage identity, memory, and history where “Solidary & Solitary” most shines. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s large-scale portraits, the only directly representational works in the show, offer great depth and warmth in fictional people who feel as real and present as a neighbor or a friend. Elsewhere, Kevin Beasley’s Untitled (Vine), 2016, takes a powerful symbol of domestic iconography, the house dress, and molds it into ghostly outlines of the human body, inviting the viewer to reflect not just on women one has known, but also ghosts of one’s ancestors, of past conversations, of all encounters that have left their marks. Encounters, for instance, like James Baldwin’s experience, recorded in “Stranger in the Village,” as the first dark-skinned man to enter one rural Swiss village, recast in a blurred, half-legible coal typeface in Glenn Ligon’s Stranger #68, 2012. Physically difficult to read, Ligon’s rendering of Baldwin’s account is one of the most productive frustrations that viewers can experience in the show.

But perhaps it is in a modest work by Norman Lewis that the ideas of the show become most visible. In Untitled—Circular Progression, 1953, a series of loosely-sketched ink figures swirl around a large central vortex. These anonymous figures—who find their counterparts in the haunting Easter Rehearsal, 1959, nearby—are engaged in a variety of activities, from talking to running to playing, even as they are caught up in the maelstrom. At the time of its creation, Brown v. Board of Education was still tied up in court, Jim Crow still ruled in the South, and the Civil Rights Movement had won few major victories. Yet black artists across genres—Ellison, Wright, Armstrong, Ellington—continued to create groundbreaking works, despite the resistances they faced. Given the political context of its creation, one wonders, then, how to read this image: whether these individuals are disappearing down the vortex of history, or whether they are in fact part of the generative force of the spiral? Closer examination offers a telling clue: gazing outward from the center of the storm, easily missed by the casual observer, is a symbol of alertness, of witness, of full and active engagement in the world. At the heart of this vision of his community, Lewis depicts a wide-open human eye.

Editor's Note

“Solidary & Solitary: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection” is on view through January 21, 2018, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.