What’s Left Behind: “The Beauty Fools”

Benjamin Morris unpacks the mythology of a new book that showed up on the doorstep of two artists.

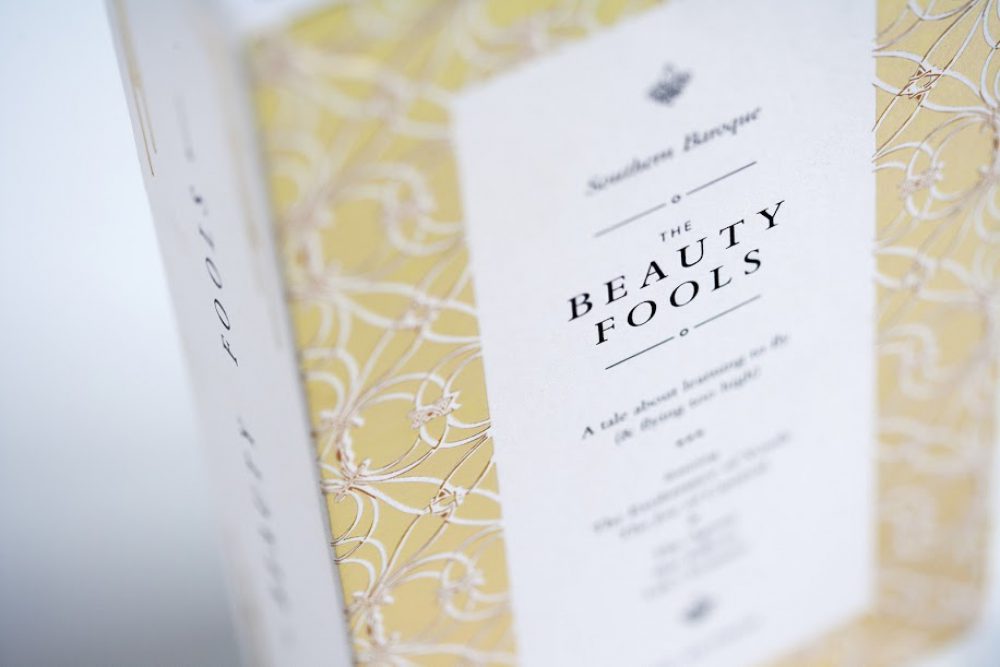

The Beauty Fools, edited by Timothy Alan Weeks and illustrated by Lala Raščić. Courtesy the artists.

An epic Odyssean journey around the South. A Bildungsroman channeling Goethe, Salinger, and Twain. A Joycean street-by-street cartography of New Orleans. A Hunter S. Thompson-esque bender, a year-long narcotics-fueled joyride through Louisiana, Texas, and Mexico. A lyric meditation on the nature of identity, the search for the self, that owes as much to Marcus Aurelius as it does to Walker Percy. An O’Toolean picaresque sketch of the colorful characters of the Crescent City and a saga of a doomed romance that would have pleased even Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald. All these things and more, The Beauty Fools escapes any easy summary: Like the city of its attention, it requires immersion, rather than description, to understand.

Published in early 2016, The Beauty Fools, an anonymously authored novel edited and published by Timothy Weeks and Lala Raščić, is the novelistic equivalent of Churchill’s characterization of Soviet Russia: “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Though the identity of its author remains unknown, the novel reflects a deep knowledge and unabashed love of the city of New Orleans and blends a wild, formal ambition with a clear homage to its literary forebears, striving to earn a place alongside them on the shelves. Does it succeed? Partly—if nothing else, The Beauty Fools is unlike anything else you will read for many years.

With such an unusual work, the circumstances of its creation are as much a part of the story of the book as the story in the book: According to Weeks, a New Orleans resident and a publisher of children’s books, the manuscript arrived on an electronic disc in his mailbox in late 2009, with only a cryptic note attached and no identifying information save the postmark, traceable to a museum in the United Kingdom. Uncertain how to respond and with no further communication from the author, Weeks read the manuscript, and, enamored of the story, decided to go ahead and publish the book. In its original form, the manuscript, he says, approached 200,000 words, and it took Weeks four years to edit it down to a manageable size.

Though its literary conventions, characters, and styles are varied, the plot of the novel is fairly straightforward. Boy (Blake Kennedy) meets girl (Miss Peaches), or rather meets girl plus girl’s boy (Eliot Dejan), and in an attempt to cure his own malaise—à la Percy’s The Moviegoer—sets off on an adventure with them both. Leaving Jackson, Mississippi, where the novel opens, for New Orleans, the threesome, shortly to become a foursome when they pick up the street preacher and poet Doctor Kookie, proceed to ricochet around the Gulf South—through Texas, Mexico, and Florida, but always returning home to New Orleans—in pursuit of self-actualization and realization.

And drugs. And alcohol. And art and culture and music and witty conversation and sex and performance, as much as they can handle, and more. Indeed, most of the novel consists of the characters lurching from one hedonistic escapade to the next, consuming every available substance they can find with astonishing speed and fortitude, whether dozens of raw oysters in the French Quarter, pills of unknown provenance in northern Mexico, or hours-long meals at Commander’s Palace with lines of cocaine for dessert. Rare is the scene without consumption of some kind, a pursuit that, over the course of The Beauty Fools, becomes less a pursuit of mere carnal pleasure than the pursuit of an ideal, of an aesthetic.

Lala Raščić, IX. Idiot’s Odyssey, 2016, From the Book The Beauty Fools. Courtesy the artist.

Enter Raščić. Just as Weeks edited the text—cutting the manuscript down to a readable size, streamlining the dialogue and story, and adding portions for clarity and continuity—Raščić, an artist and designer, visually brought The Beauty Fools’ characters to life. She photographed live models enacting select scenes from the novel and rendered them in a lush, atmospheric, pen-and-ink style for each chapter’s frontispiece. The fruits of her work are now on display at Coup d’Oeil Art Consortium, along with copies of the book and drafts of the artists’ working processes. Evoking simultaneously the grand rhetoric of Art Deco, the visual excess of Baz Luhrmann, and the mystic symbolism of Carl Jung, Raščić’s images more than just illustrate the text; they illuminate the mood of practiced decadence at work in the novel.

Sprawling, rambunctious, and ambitious, that aesthetic—one that champions beauty, passion, and performance above all—is the key to entering the novel. For at its heart is a central mystery: Who are we, to ourselves and to others? Debated and dissected over 400 pages—when not altered or escaped through drugs, sex, or booze—identity remains the elusive prey of the story, for each of the protagonists. Eliot, the consummate performer, seeks to charm everyone he meets, including himself. Peaches, his leading lady, looks to seduce her marks using style and affectation, hiding behind feather boas and smart hats. Blake, seeking to transcend his inaugural mediocrity, searches for a new self to replace the old. Only Kookie—perfectly at home in his role as both griot and Greek chorus—seems at peace with himself, content to roll another spliff while unrolling lines of poetry. When answers to their questions are unforthcoming, performance—masking, flippancy, and hedonism—must suffice. Indeed, the moments when these characters’ illusions of themselves are shattered become some of the most tragic and moving in the book.

As these questions drive the novel, they also fuel the story of its creation. Though Weeks says all identifying information about the author has been lost—a convenient excuse, but, if true, regrettable—a careful reading of the manuscript does reveal certain clues that invite some speculation. Certainly the author has a deep knowledge of New Orleans, the kind of knowledge that cannot be obtained overnight: accents, dialects, cultural codes and references, places, traditions, and peoples. If James Joyce famously wanted future readers of Ulysses to be able to reconstruct 1900s Dublin street by street, the same mission is at work here; anyone with this kind of spatial awareness of the city must have lived here and studied its occupants for years. Such a novel would not be possible otherwise.

Installation view of TIMOTHY ALAN WEEKS AND LALA RAŠČIĆ’s “The Beauty Fools,” which includes illustrations, archival materials, and other objects, at Coup d’Oeil Art Consortium, New Orleans. Courtesy the artists.

Yet that same knowledge comes at a price—many of the references involve stereotypes of the city’s residents that suggest an eagerness to make the right jokes, to fit in as a New Orleanian. Hauled in for dismissal are people from Slidell, Kenner, and Chalmette, for instance, just for being from there. Likewise, just about every cultural institution, restaurant, and bar beloved by today’s locals is showered in praise, from the Prytania Theatre to the Mother-in-Law Lounge. Indeed, the novel makes a point of praising famous men. This overexuberance to include everything but the kitchen sink reeks of a desire for social acceptance, a desire more commonly found in transplants to the city than in natives.

Other clues suggesting the author’s age (young, under 40) and geographic upbringing (Southern) dot the manuscript, but past this point, speculation remains speculation. Until the author comes forward and claims responsibility, or more details of the original manuscript emerge, speculation is all we have. What is certain, however, is that the author has written a brilliant book: funny, smart, and playful, with a spectacular mind for language and ear for accents, and one that searches through profound existential questions with a warmth and humanity that at once reveals and celebrates the absurdity and fragility of life. That the author has spent years researching his story and his subjects—including, worryingly, their penchant for narcotics—is evident, and we are all to benefit from his razored insights into both the makeup of this city and the nature of ourselves.

This is not to say the novel is flawless, or that, in the pantheon of New Orleans literature, it immediately rises to the level of Percy or O’Toole. Its hedonism becomes repetitive; its prose at times flattens like a pancake (declarative sentences starting “I [verb]” are too numerous to count); and its insistence to make the right jokes, to praise the right things, feels eager, even forced. Most concerning of all, though, is its blurred temporal horizon: The book occupies an unclear time period seemingly four or five years after Hurricane Katrina but which still includes entities and places that disappeared long before the storm, such as K&B drugstores and Maison Blanche. Take, for instance, a scene in which a character passes Ruthie the Duck Lady on a nighttime stroll around the Quarter and then returns to his suite in the Roosevelt Hotel. This never could have happened: Ruthie died in September 2008, and the Fairmont didn’t reopen as the Roosevelt until 2009.

Most oddly, the storm is never once mentioned in the book, which is surprising, given the extensive geographic ground the novel covers, including driving repeatedly through presumably storm-ravaged areas such as the Ninth Ward. The omission is glaring, and looms over the whole of the story. Weeks, aware of these inconsistencies and gaps while editing, suggests that this smearing of the time horizon may constitute a moral project, the author creating a mythology of the city that transcends any one month or year. Perhaps. But for the alert reader, such moments disrupt the dream in uncomfortable ways, destroying the illusion of comprehensiveness the book purports to create.

That said, without betraying any further details of the plot, the central questions of The Beauty Fools elude easy answers, which is, somehow, satisfying. As Blake comes to understand by the novel’s end, certain things ought not to be fully known, lest we destroy their mystique by our investigation. For now, it will be up to readers to enjoy the mythology of the project for its own pleasures, and to form their own judgments of the book—to decide where among its literary predecessors it stands. Regardless where those judgments fall, the arrival of this novel suggests a remarkable literary talent, one for whom—anonymous or not—we have only to be grateful. And hopeful—that his feet will begin to itch, his fingers will begin to twitch, and his next manuscript will land in someone else’s mailbox soon.

Editor's Note

Timothy Alan Weeks and Lala Raščić’s “The Beauty Fools” is on view through April 9, 2016, at Coup d’Oeil Art Consortium (2033 Magazine Street).