Order in Chaos: Diana Al-Hadid at the Newcomb Art Museum

Charlie Tatum sees a different side of Diana Al-Hadid’s practice in a recent show at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University.

Installation view of Diana Al-Hadid’s Head in the Clouds, 2014, at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University. Polymer gypsum, fiberglass, steel, foam, wood, plaster, clay, gold leaf, and pigment. Courtesy the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York.

Brooklyn-based sculptor Diana Al-Hadid is best known for her large-scale installations, hulking sculptures comprised of haphazard stacks of intricate honeycombed walls, cast organ pipes, and striated avalanches of plaster. While these sculptures, which approximate medieval cathedrals flipped on their heads or utopian towers from the Soviet avant-garde, have defined Al-Hadid’s career, a recent exhibition at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University presents a less chaotic side of the artist’s practice.

The exhibition is centered around three sculptural works. Though many of her earlier pieces have looked to the body to inform both design and scale, these sculptures mark Al-Hadid’s first forays into representing the human form. Al-Hadid frequently, including in an interview that appears in the museum’s exhibition pamphlet, aligns her practice with the act of building rather than with metaphors of decay. The saintly figure of Head in the Clouds, 2014, is perhaps most indicative of the additive nature of Al-Hadid’s process. For the sculpture, Al-Hadid started with a clay head originally created for another piece and progressively affixed elements in plaster, fiberglass, steel, and other materials. The referents include a cascading pile of fabric, the outline of Jesus’ cloak in a painting by Duccio di Buoninsegna, and a model of the artist’s childhood home in Ohio. Art history and science often appear in Al-Hadid’s works, either as visual allusions or as conceptual systems—like in Spun of the Limits of My Lonely Waltz, 2006, where she used the dance’s steps to guide where she would eventually erect structural supports. Some of her other sculptures look to Peter Bruegel the Elder’s The Tower of Babel, the Large Hadron Collider, and a 13th-century water clock designed by engineer Al-Jazari. For Al-Hadid, these layerings of materials and of sources are part of one creative impulse.

In Mortal Repose, 2011, the artist’s first work in bronze, shows a woman’s torso (no head, no legs) seemingly melting across a stepped pedestal; two deflated feet rest near the floor. Taking this motif of softened flesh one step further, in Blind Bust II, 2012, Al-Hadid has created a rectangular base entirely out of bronze drips, replacing the interior where the support should be with empty space. But compared to Al-Hadid’s more grandiose sculptures of exhibitions past, these three works on view feel more like one-off studies, highlighting the experimentation that’s integral to the artist’s process. They come off as ultimately unresolved, studies for something to come.

Diana Al-Hadid, The Weightlifters, 2015. Polymer gypsum, fiberglass, steel, plaster, aluminum leaf, and pigment. Courtesy the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. Photo by Matt Grubb.

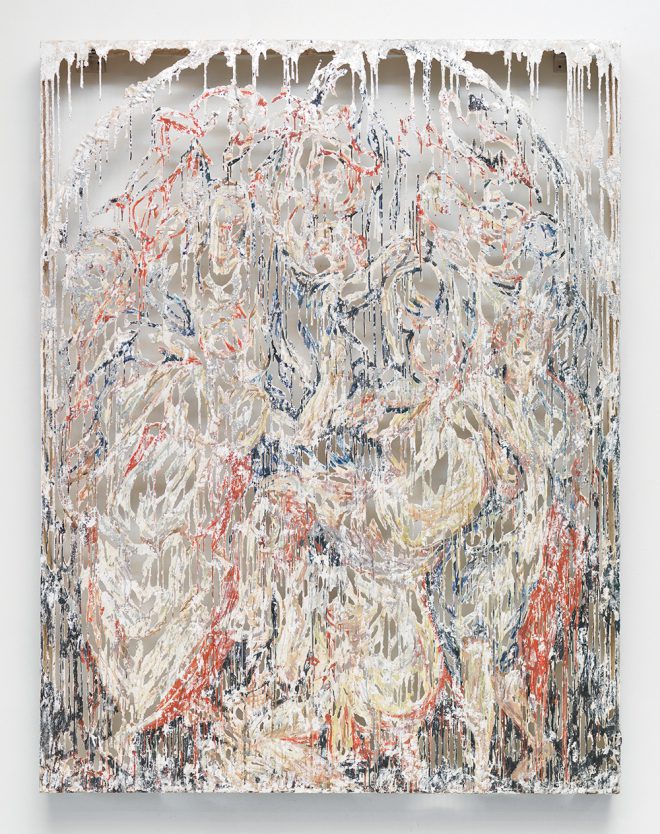

The artist’s two-dimensional wall works, which comprise the majority of the exhibition, in contrast, feel much more complete. These pieces, constructed from screens of drips made of polymer gypsum, fiberglass, and plaster supported by steel frames, show a controlled and subtle facet of Al-Hadid’s practice. Her splatters stay within their rectangular constraints, and images appear in the pale pinks, greens, and yellows only from a certain distance. While these works are visually similar to Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings, they are more akin to Rachel Whiteread’s casts of the forgotten negative spaces underneath chairs, beds, and staircases. To create these works, Al-Hadid loosely paints over projections of historical paintings, often of Biblical subjects. The resulting panels take on new sculptural lives as tracery that delineates the space of a canvas behind it. In this case, the painting itself was never there.

But Al-Hadid plays fast and loose with her sources, and the painting-sculptures are more records of the process of rebuilding and reimagining a historical work of art than signifiers of something concrete. She admits that growing up in a non-Christian household affords her extra leeway with Biblical art historical subjects. She sees them as malleable scenes instead of gospel, and her process literally abstracts her source material. We are left seeing only remnants of a Lamentation scene by Jacopo da Pontormo in The Weightlifters, 2015, and a congregation of arches and buttresses in The Square, 2014—symbols reduced to formal exercises. Two works on paper echo this technique with layers of Conté crayon, charcoal, pastel, and acrylic paint nearly covering translucent sheets of Mylar completely, the drawings seemingly suspended in their frames.

The quietness of these wall works reminds us that, while her sculptures can seem chaotic, Al-Hadid’s practice has always relied on a rigid adherence to order, even if that logic is particular to her own headspace. And while they may not be her most memorable works, the exhibition at Newcomb Art Museum gives a peek into Al-Hadid’s world, one where form trumps meaning.

Editor's Note

“Diana Al-Hadid” was on view May 9 – July 24, 2016, at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University.