On Fashioning Memory Lane: The Photography of Bill Yates

Laurence Ross visits Bill Yates’ exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and contemplates how time is embedded in photographs.

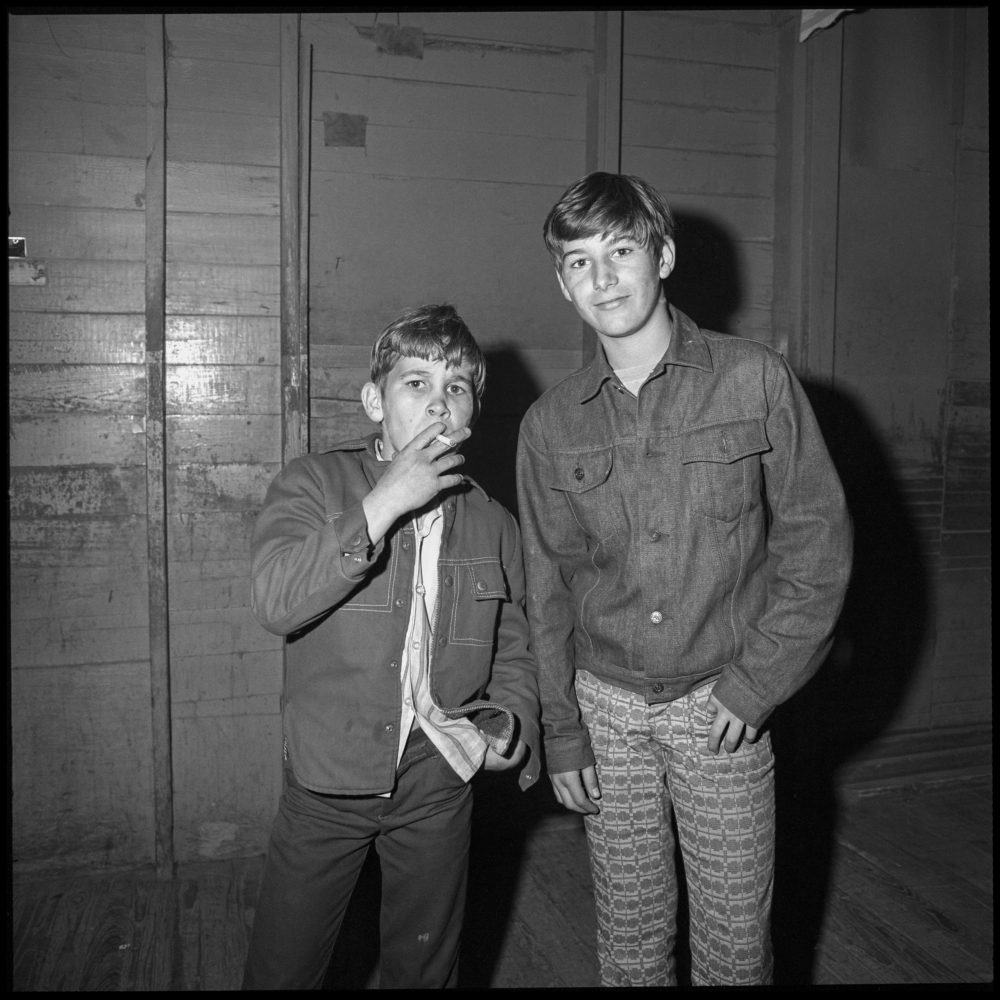

Bill Yates, Untitled, R38, #9, 1972-73 (printed 2015). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

I seemed to be living a dual existence.

E. B. White, “Once More to the Lake”

There is an impulse, when considering the portraits Bill Yates snapped at the Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink in the early 1970s, to discuss the photographer’s story. The story behind this particular set of photographs is, albeit, interesting: a young student of photography documents the nuances of this recreational hang-out in Tampa, Florida (along with the people that were doing the hanging out) and then somehow never develops the bulk of the film. He pins contact sheets or test prints each week at the rink, and each week the skaters become more comfortable with his presence, easing into the idea of this stranger walking among them, until eventually the skaters begin to show off, perform. Then, some 35 years later, the negatives are pulled out from a storage bin or drawer, and Yates, a man who now primarily works in landscape photography, begins to sift through his brief undergraduate foray into portraiture. But this story is not what lends the photographs their artistic merit; Yates’ photographs hold their own. Simply put, they are excellent portraits.

Richard McCabe, who curated “Bill Yates: Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, refers to the photographs as a “visual time capsule.” But this description doesn’t quite fit; it’s too succinct, as the word capsule implies that the time is somehow contained. Critics and curators have framed Yates’ photographs as the moments just before the space program and Disney World changed that area of Florida forever. But in looking at these portraits, what becomes most striking is not how they convey a particular period in time, but rather how they demonstrate time’s movement, as stagnant as it is swift. There is much to recognize in these faces, whether we were teenagers in 1972 or not.

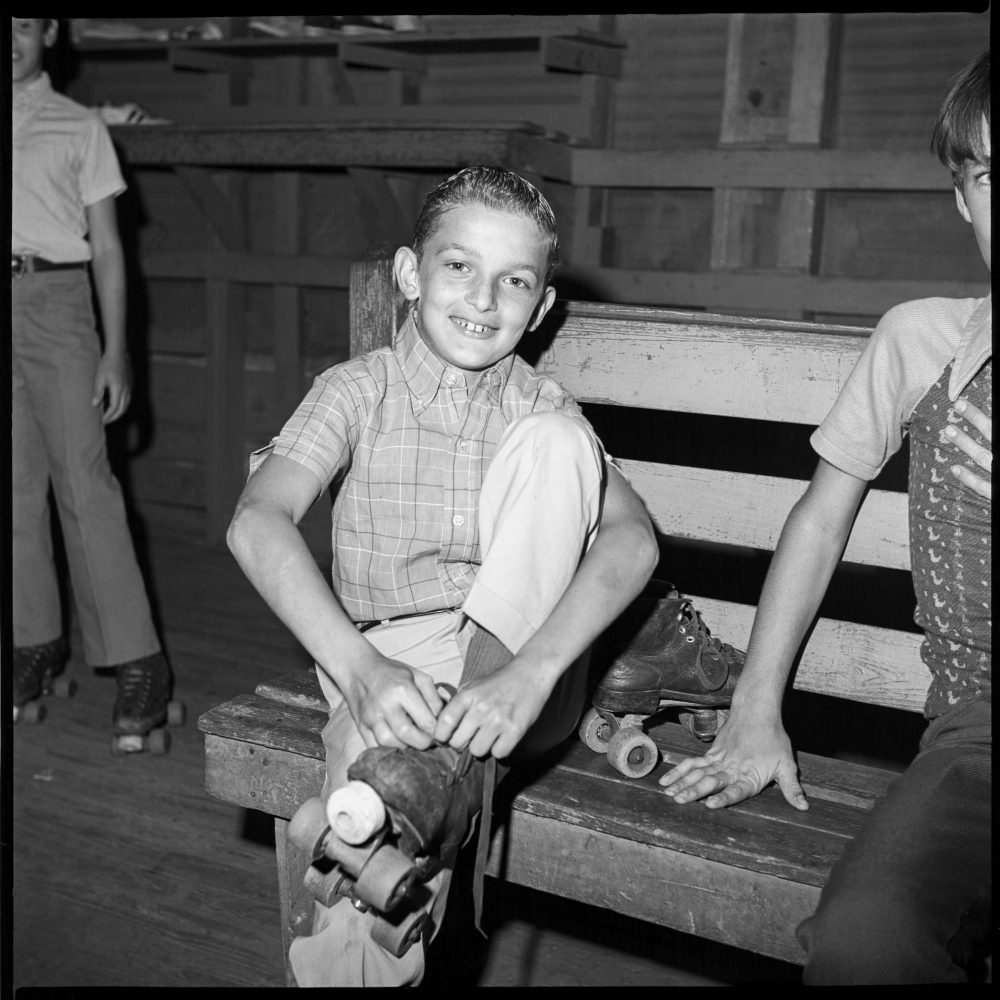

A boy on a bench holding his stomach, candy bar wrappers and an empty soda bottle on the ground. A girl sitting alone, with a distant gaze like she’s lost (or remembered) something important. A boy with a bell chained around his neck, a scar above his slim bicep, curls combed and parted to the side, lips parted, squinting just past vacancy. More playful than Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958) and less menacing than William Klein’s photographs of children playing with pistols (1954), these photographs and the people in them feel, well, familial. A weekly reunion in which banality and the fleeting thrill of the weekend, the drag of apathy and the spike of hormones could glide and collide into an unfolding of attitudes—and faces—that ultimately gleam genuine. One boy with big ears, wide teeth, and freckles speckling his nose reminds me so much of my father that I texted him to ask how old he was in 1972, not because I thought the boy was him but because I thought the boy could have been him.

Bill Yates, Untitled, R7, #5, 1972-73 (printed 2015). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

One of the first photographs I encountered when entering the exhibition was an interior of the skating rink’s supply room. With skates and spools of tickets and empty cases of 7UP, the photograph looks old in a way that suggests the skating rink was built long before the months Yates spent documenting it in 1972 and ’73. Though distanced by time and location from the depression-era Alabama documented by Walker Evans, there is something similar here, an equal interest in people and the ephemera of their lives. With Evans, we are shown a bed frame, an oil lamp, a broom, a pair of well-worn boots. With Yates, we are shown a bare bulb, an analogue clock, pad locks, skeleton keys. The skates, torn from frequent use, are arranged loosely by size—the stoppers scuffed, the pompoms patinated. The tickets read “admit one,” but what are we, the onlookers, being admitted to? America in 1972? Not exactly.

These portraits were taken the same year that Halston—who had dressed the jet-set generation of the 1950s and ’60s and stars like Liza Minelli—became the first American fashion designer to trump French Couture at the Battle of Versailles; with his menswear-inspired lines and ready-to-wear collections, a new image of feminine elegance emerged in print advertising. But at the Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink, we are far, far away from that brand of glamour. The fame captured in Yates’ images is local, momentary, personal—and had remained in a closed circuit until the photographs recently reemerged to a wider audience. The sitters, though rarely actually sitting, have a sense of ease about them. Not a happiness, exactly, but a contentment with whatever is at hand. In part, Yates stands among his subjects as a peer, a peer at least in age, which surely enabled this naturalness. Yates began as a stranger snapping portraits, and then, through repeated visits, gained a sort of access. According to the photographer, a sense of comfort settled in after his initial visit. For some of his subjects, skepticism seems to have gradually given way to safety, the wooden floorboards becoming more stage than skating rink.

In one photograph, two boys look so similar I assume them to be brothers. The older one is smiling, a sweet face that would fit right in as part of a Sears family portrait; the younger one is inhaling on a cigarette, staring into the lens with perhaps equal parts suspicion and defiance. Another photograph shows a young couple in a sort of embrace. The boy looks toward the camera, engaged, curious, proud, possessive; the girl has her eyebrows raised and her mouth open, physically locked in the photograph but mentally focused on something outside of the frame. There is more than one middle finger flipped toward the camera in these photos, but they seem almost playful, daring, feeling out the boundaries.

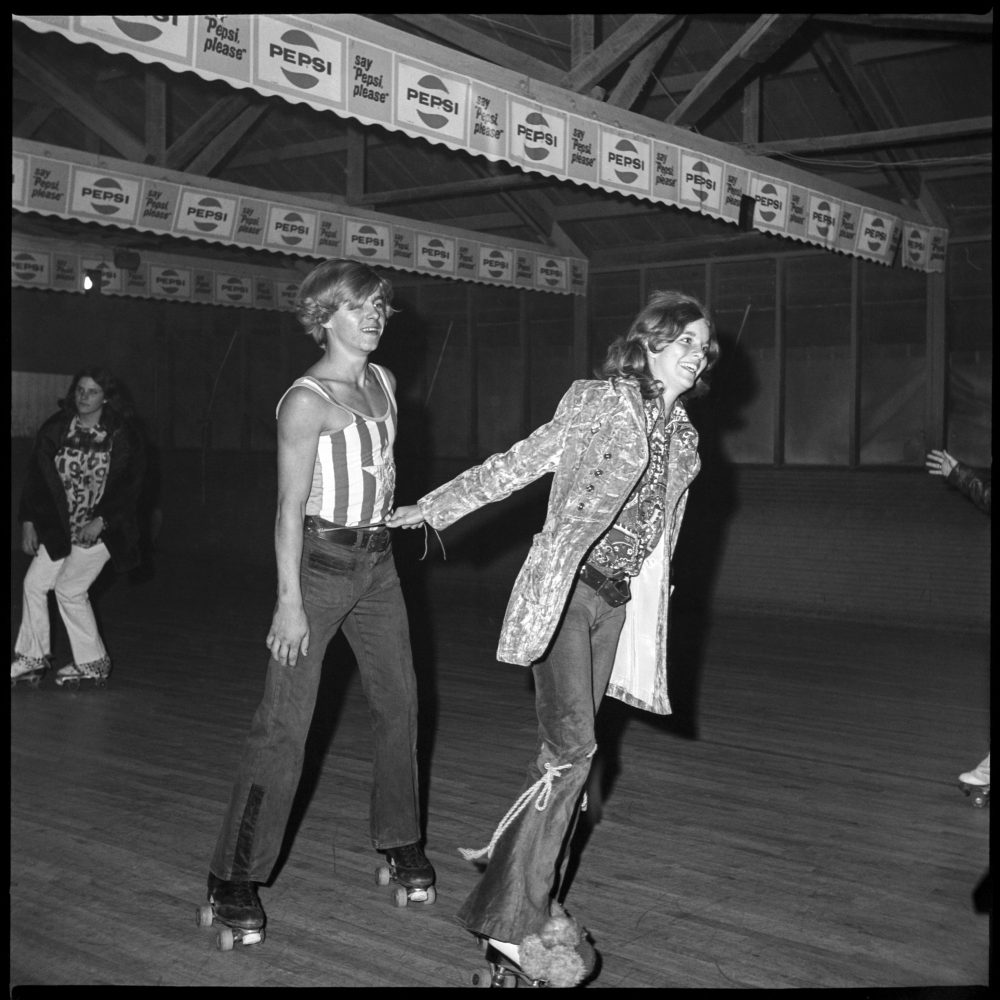

Bill Yates, Untitled, R30, #1 1972-73 (printed 2015). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

To skate at a roller rink is to travel on wheels round and round in a circle, the individual swept up into the larger movement of the space. Geometrically, this is not how time is typically considered. Time, even if one has the ability to travel back and forth, is commonly considered linearly. American author E. B. White writes of his own relationship to time’s passing in his 1941 essay “Once More to the Lake.” White takes his son on a trip to the very same lake he visited with his father thirty-some years before, and fears how time will have “marred this unique, this holy spot.” This reaction is akin to many of those I overheard from fellow museum-goers as we all peered into this past presented by Yates. The common response was wonderment, not so much at the photographs themselves, but at the year 1972. What were you doing? Who were you dating? Where has the time gone? In a photograph showing a girl dragging a tank-top clad boy round the rink by the leather laces attached to his belt, the boy is stiff and treelike, the girl intent on the capture. The components are all-American: bell bottoms, Pepsi banners, stripes and a star; the recycled narrative of (fore)play vibrant once again in black and white. The past, present, and future collapse, flattening time’s linear hierarchy like a penny beneath the force of a train, the year rendered momentarily indiscernible—or irrelevant.

Since the prints are untitled, we have to work harder. More effort is required to derive an articulate understanding (much less intent) from the portraits. Titles would have provided another framing device, an extra border for us to lean on, to create meaning from. We are asked, instead, to take these scenes at face value: wide corduroy, loud prints, thick belts, button flies; freckles, fingernail polish; dancing, an arm draped over the shoulder of another, kisses.

White remarks, “It is strange how much you can remember about places like that once you allow your mind to return into the grooves which lead back. You remember one thing, and that suddenly reminds you of another thing.” For White, memory is a road upon which one can walk back and forth. Walk farther back, and you can see more of what you have forgotten, as if you are following a wrinkle in the brain and rediscovering what has remained hidden in the folds for decades. And even within Yates’ photographs, we see characters resurface. The boy in the tank top who seemed so bound to the girl who strung him along emerges again from a black background, burning cigarette in hand, lips buried in the curly hair of another girl. What transpired here? What has happened in the meantime? The girl’s startled face seems to say it all: Don’t ask me. This just happened.

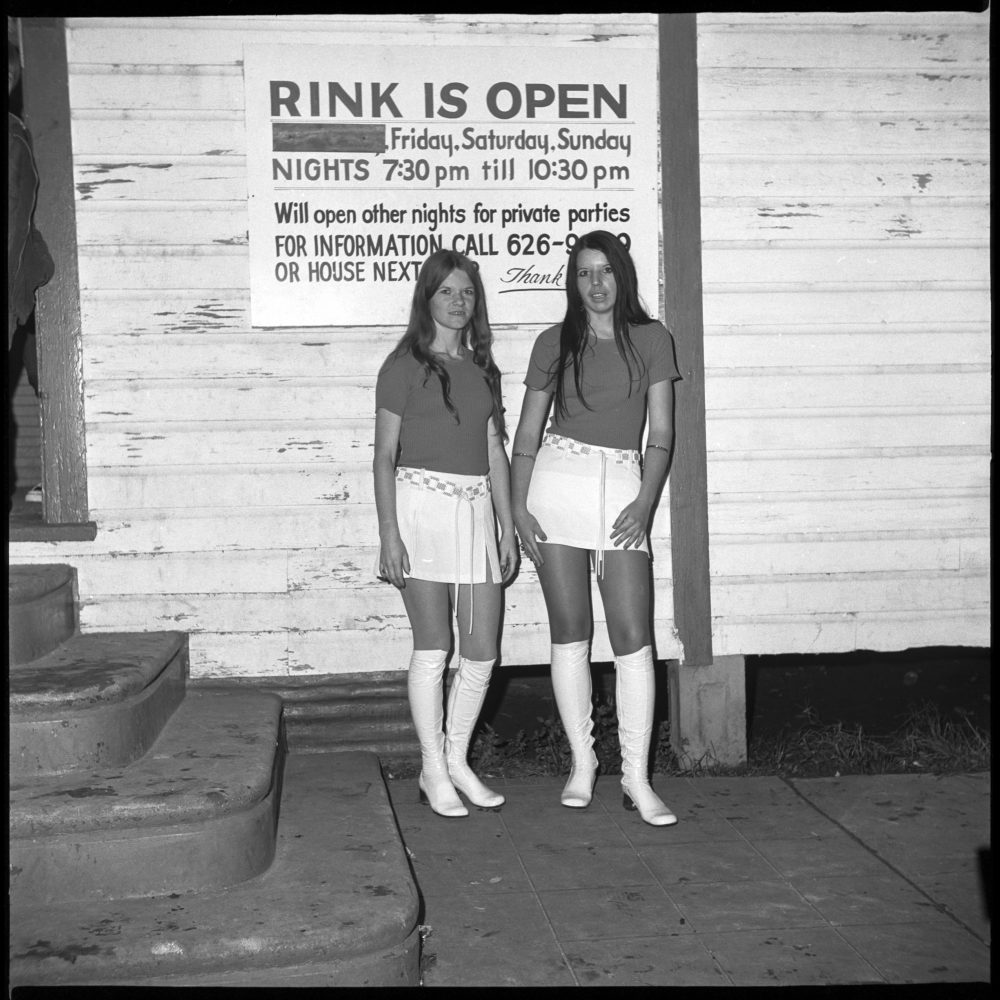

Bill Yates, Untitled, R45, #8, 1972-73 (printed 2015). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

The style of these portraits is one that is recognizably of its time. Now, when selfies surely dominate the images we create of ourselves, this open participation of a crowd of relative strangers seems inconceivable. Today, there would be concerns about rights, publication, the Internet, images out of our control. The ability of a photographer to witness—and elevate—the everyday seems to be waning, at least in regard to the candid portrait. In these photographs, Yates is deeply interested in humanity, and he shot with a direct, raw, and spontaneous flare. We would be hard-pressed not to think of Diane Arbus—an acknowledged influence on Yates. Like Arbus, the young Yates fostered relationships with willing subjects, relationships that resulted in a participatory (and at times, gleefully staged) series of portraits that document a specific time, geography, economy, and fashion. According to Yates, these people saw themselves through his photographs in a way they had never quite seen themselves before. When he pinned the images to the walls of that rink for the first time, they saw likeness. These portraits revealed what no bathroom mirror had ever managed to show: the powerful beauty of the seemingly mundane, the recognition of something within ourselves we did not know was there.

“I would be in the middle of some simple act,” says White. “I would be picking up a bait box or laying down a table fork, or I would be saying something, and suddenly it would be not I but my father who was saying the words or making the gesture.” Whereas White goes on to describe this feeling as “creepy,” the Yates portraits evoke something more akin to possibility. This boy could have been my father. That boy could have been me. I think it important to clarify that these photographs cannot universally evoke nostalgia. The word nostalgia implies that the feeling or time or place we re-experience, we long for, is a part of our own past. But these portraits are so particular in their context that this past is not ours (though we may easily imagine it to be). What we experience is not nostalgia, but rather a sort of fantastic escapism, perhaps a longing sentimentality for an era we believe to be bygone and, in all likelihood, misconstrue as being a simpler time.

One final photograph: two girls dressed in matching outfits stand in front of a sign advertising the operating hours of the Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink. The sign reads “RINK IS OPEN.” Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights are listed but Thursday has been blocked out: a premonition that however cyclical, time for the individual is fleeting. In remembering childhood, we go back to a time when we were healthy, hopeful, young, beautiful. Creative, curious. It’s about the beginning of the story, our story. Yates’ portraits allow us to approach the present moment as if we were in childhood, and the newness, the nowness of the experience can yield an insight we would not otherwise have access to. Reliving does not need to be about going back along the tracks of memory, as E. B. White suggests. Reliving can be living in the moment in a way we could never have done before.

Editor's Note

“Bill Yates: Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink” is on view through January 17, 2016, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.