Hero of the Streets: “George Dureau: The Photographs”

Photographer Pacifico Silano looks at a new book of George Dureau’s photographs and thinks about how Dureau’s work has influenced his practice.

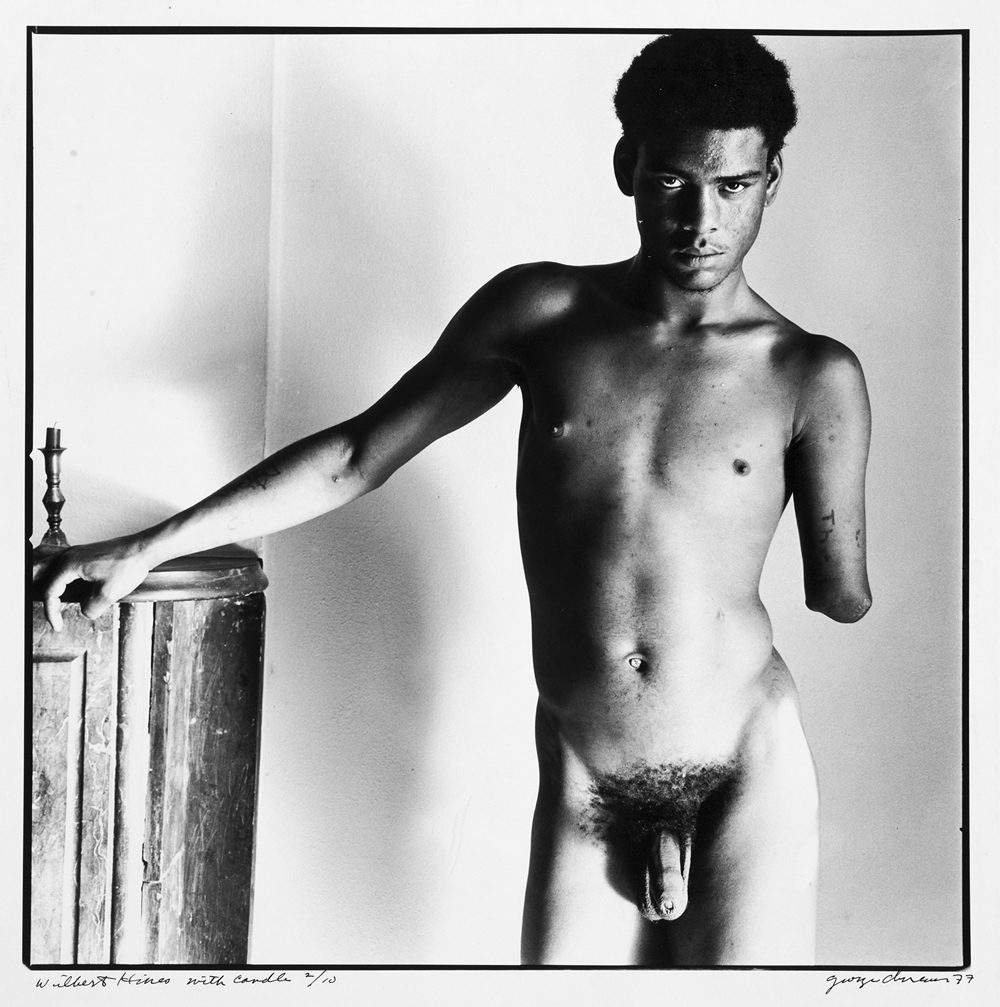

George Dureau, Wilbert Hines, 1977. Courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, and Higher Pictures, New York.

I remember the first time I saw the work of George Dureau. I was a freshman in college, roaming through the photography section of the campus library. I pulled a compilation of images devoted to the nude male form off the shelf. The book was well worn, the cover was creased, and its pages were dog-eared at the corners. George Dureau’s portrait of a stoic black man with an amputated arm is featured on the front. The piercing gaze of that model is forever burned in my memory.

It’s an image I’ve encountered countless times over the years through my research of homoeroticism in photography, and yet it’s never lost its power. The man—Wilbert Hines—like many of Dureau’s models, sat for numerous portrait sessions over the photographer’s career. This trust and his subjects’ willingness to be documented, often times in the nude, stands out when looking through Aperture’s recently published monograph George Dureau: The Photographs. Each of the artist’s images contains nuanced references to gestures found in historical paintings. It comes as no surprise then that the photographs were initially taken as figure studies for Dureau’s own painted works. But, in the end, these images have become art in their own right.

In a country that is plagued by inequality, the work of George Dureau lives on with new poignancy after his death in 2014. Looking through this collection of photographs shot over the span of a remarkable 40-year career, I can’t help but feel the immense empathy and affection the artist had for his countless models, many of whom were young black men, people with dwarfism, and amputees who lived on the margins in New Orleans. The sensitivity and care for his subjects separates Dureau’s work from the contentious racial politics of his younger contemporary, Robert Mapplethorpe. The objectification of the black body is nothing new to the art world. But it comes as a great relief to see someone like Dureau thoughtfully portray intimacy with his models, while not erasing the distance between their otherness and him.

Many of the works in this monograph feature male models confronting the viewer with their gazes. Each portrait is a seeming study in resiliency in the face of a society that has turned its back on them. We see this in the men’s faces and the ways in which they held themselves before Dureau’s camera. Absent is the glossy, commercialized aesthetic of most studio photography; in its place is a natural subtlety. Beautiful, diffused light envelops each man.

Surprisingly, this is only the second time a book of the artist’s work has ever been published. (The first, New Orleans: 50 Photographs, dates back to the mid-1980s.) It’s shocking that Dureau has been so underrecognized given how influential his work has been to countless photographers. With this new publication comes the opportunity to expose a new generation of image-makers to the beauty of Dureau’s portraits, which transcend the hard truth that all men are not equal in the eyes of society. It’s something that Dureau’s models knew all too well. The book ends with an image of Troy Brown, a hustler from New Orleans. Standing before the camera completely naked, his hands on his hips, Brown’s presented to us as if he were an Olympian, a hero of the streets.

Editor's Note

George Dureau: The Photographs was published in May 2016 by Aperture. An exhibition of Dureau’s paintings, drawings, and photographs is on view August 6 – September 17, 2016, at Arthur Roger Gallery (432 Julia Street) in New Orleans.