Immediate Gratification: “Self-Processing – Instant Photography”

Taylor Murrow reviews the Ogden Museum of Southern Art's exhibition of photographs shot with instant film.

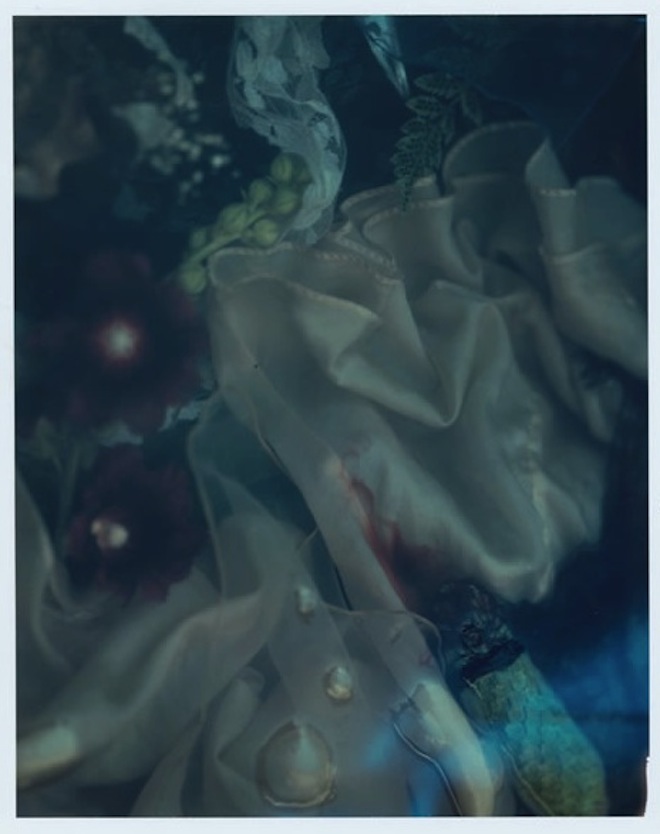

SALLY MANN, Untitled, 1983. Polaroid Print. Courtesy the Artist and Gagosian Gallery, New York.

“Self-Processing – Instant Photography”

Ogden Museum of Southern Art

925 Camp Street

October 4, 2014–January 5, 2015

The simple Polaroid snapshot, introduced by Edwin Land in 1947, is a symbol of American nostalgia and ease. Instant photography rendered the particularities of the darkroom and inconveniences of the lab irrelevant for the amateur photographer; simply click and watch the image appear on photographic paper, no special skill set or knowledge required. Polaroid stopped making film in 2008, though its characteristic soft focus and hazy glow now have been co-opted by Instagram filters that are quickly shuffled and applied with a gentle tap on a touchscreen. Despite the form’s novice associations, the seemingly lowbrow Polaroid has long provided fertile ground for artists. Curated by Richard McCabe, the selection of works in “Self-Processing – Instant Photography” is a testament to its enduring strength and versatility.

Sally Mann’s Untitled, 1983, stands out with the graceful fluidity and delicateness of a watercolor painting. Jen Ervin shows how good old-fashioned light and shadow can be effective tools for abstraction in instant photography; her black-and-white prints highlight the gentle curves of a female figure set in a wooded landscape. Several other artists in the show employ abstraction, using manipulation or inventive processes within the form.

At times, the abstractions are a natural side effect of the processes themselves, as in works by George Blakely, who collected discarded Polaroid photos as a sweeper at Disneyland in the 1970s. Likely tossed out by tourists who didn’t want blurry or fingerprint-laden pictures of Mickey Mouse and the Magic Kingdom, these found prints are placed over enlarged versions of the images, evoking the wistfulness of the Polaroid through strangers’ warped and discarded memories.

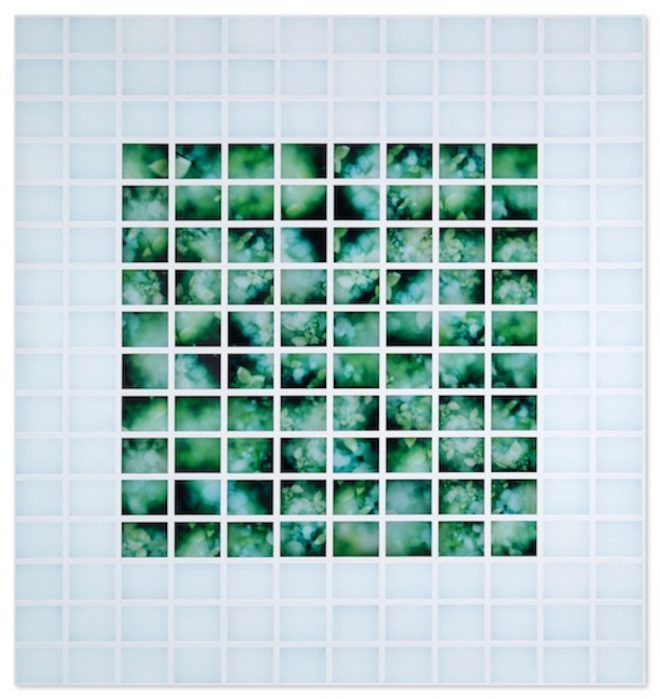

While it doesn’t quite replicate the magic of the darkroom process, the act of immediately pulling a physical photograph from a hand-held box and watching light and chemicals manifest an image was (and is) a transfixing experience for generations of photographers—amateurs and professionals alike. Works like John Messinger’s massive mosaic of images depicting large computer monitors toy with this loss of tactility in everyday photography today. There’s an inherent paradox in using outdated technology to dissect our increasingly digital world, yet still instant photography lives on.

John Messinger, Some of What We See, 2014. 192 Fuji FP-100 C-Prints. Courtesy the artist and Unix Gallery, New York.