Finding the Essence: An Interview with Fred Bookhardt

Retired architect Fred Bookhardt holds a special place in his heart for the many old buildings of New Orleans. Jonathan Traviesa photographs Bookhardt in his Marigny home.

Editor's Note

Kicking off a series of conversations on discovery, Amy Mackie talks with Fred Bookhardt about his work as an architect, his world travels, and his eventual return to his hometown after nearly 40 years away.

Through the Center for Gulf South History and Culture's artists and writers program, I found myself last April with a guest studio residency at Fred Bookhardt’s beautiful Marigny home. I had just returned to New Orleans to work on my book about the city’s artist-run spaces, and we quickly learned we shared a love of New York, an appetite for wanderlust and adventure, and a great respect and admiration for creative thinkers of all stripes.

Amy Mackie: When and where were you born?

Fred Bookhardt: I was born in New Orleans on May 14, 1934.

AM: What was it like growing up in New Orleans during that time?

FB: Lake Pontchartrain once had many fishing camps on stilts dotting its shores. My favorite place to go when I was a kid was a place we called Jake and Lil's Rat’s Nest. You had to go out on a breakwater to reach the front door. If you faced the bar, on the left was a pier with the outhouse, also on stilts. My father would tell us to drop our crab nets next to the outhouse because the crabs were fatter there. Fishing boats would pull up to a ladder on the side of the building and climb up to get a drink.

Jake, a retired railroad engineer, was always behind the bar where he had many photos of Lil, his lost love. He had a wicked sense of humor. One time, a woman stormed in, wanted to know where the restroom was. Jake pointed to the outhouse. She sassed back, "No, where is your real restroom?" So Jake reached under the bar and handed her a bucket. Alas, all those camps are gone now, thanks to Katrina.

AM: Why and when did you leave New Orleans?

FB: I had imagined living in New York since I was a young boy. My glamorous aunt, Barbara, had lived there, and she had given me some playbills from the great shows she had seen (including the playbill for A Streetcar Named Desire). She lived the high life, which greatly influenced both my cousin and me. I left New Orleans in 1960 in part because I thought it was too small and too slow. I eventually returned for the same reasons.

AM: When did you decide to study architecture and why?

FB: It was a practical decision. I was tempted to try being an artist or an illustrator when I started high school but decided architecture was a better bet. Math was my best subject, and math and architecture are closely related. Algebra was the only course I took in high school where I scored perfectly. Once I began working as an architect, I always relied on math to prove how something could be done.

AM: You studied under the great architect Louis Kahn. How did that affect you?

FB: He was the primary influence on my life as an architect. Kahn did not teach us to imitate him, but instead taught us that everything had an essence. Our job was to find that essence. He also insisted that we never enter a project with a preconceived idea, and he always reiterated the importance of being a good neighbor.

AM: What did he mean when he said “good neighbor”?

FB: Take the Guggenheim Museum designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in New York for example. It was supposed to be located in Central Park, but that location was not approved by the city. Instead, the structure was erected on Fifth Avenue, squeezed between buildings with which it is not congruent.

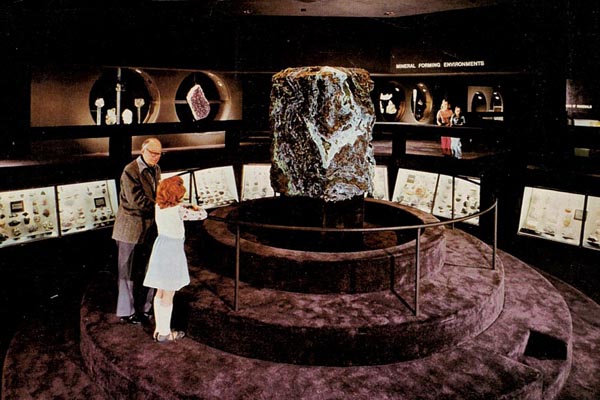

Bookhardt designed the Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Minerals in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Photo courtesy the now defunct Modern Maturity magazine.

AM: The Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Minerals in the American Museum of Natural History in New York was praised widely when it opened to the public in 1977. Can you talk about your involvement with this important project?

FB: I was working for the architecture firm Wm. F. Pedersen and Associates when he got the contract to do both a master plan for the old museum and to design a new hall for minerals and gems. The design of that hall was a good illustration of Kahn’s charge to find the essence. Luckily, I was able to spend a lot of time watching how visitors reacted to exhibits. I discovered what should not be done. No hard floors—kids loved to slide on them and scream. No long text—visitors would skip anything longer than two or three lines. Watching students interact with a teacher led me to introduce teaching pits in the museum. Normally, the kids in the back who couldn’t see the exhibit just horsed around. We planned the pits so the students sat on carpeted steps where they could all see and hear the teacher, giving the teacher control over the class.

AM: You’ve mentioned in the past that a large part of the success of the hall was due to your fruitful collaboration with others who worked for the museum.

FB: I was fortunate that the curator of mineralogy was my age. He was from South Africa and also a bit of a dreamer. The director of the museum at the time, Tom Nicholson, loved adventure and saw my design as an adventure for the museum. For the first time ever the hall was kept dimly light; the floor was carpeted and sound absorbing fabric was used to cover the walls, all in dark brown and earth tones. Vincent Manson, the curator, gave me the idea. We spoke of mining expeditions, and he reminisced about the joy of clearing the mud from a cave to find all these sparkling gems protruding from the walls. That's when I decided the hall should feel like a huge cave filled with all sorts of treasures, and it worked. Kids entered the hall with a sense of awe. Suddenly they became well-behaved children instead of screaming brats. The hall was the most fun I ever had on the job. I designed the placement of each of the 5,000 plus gems and minerals, which were culled from some 85,000 specimens. It took six years to design and construct. The completion of the hall made me realize that I had the ability to help make other people's dreams come true.

AM: What were some of your other exciting projects?

FB: I opened my own one-man firm in 1977 after the Hall of Minerals received a rave review in The New York Times, and shortly thereafter the Egyptian government hired me as an architectural consultant. This was back when Anwar Sadat was president, and it was an exciting but intense time to be in Egypt. Sadat had just made his peace overture to Israel and other Arab nations had consequently threatened to punish Egypt. Arrival at the airport was nerve wracking. My flight was four hours late, and I had no idea if anyone would be at the airport to greet me. As the plane taxied in, I looked out the window and saw that the entire tarmac was surrounded by soldiers with sub-machine guns.

AM: What was your role while you were in Egypt?

FB: I was primarily involved in the Museum of Agriculture, which was a large complex located on an island in the Nile. They wanted my advice on how to expand it while preserving its feeling of serenity. The gardens were lush and lovely. The Under Secretary of State actually gave a luncheon party for me in those gardens. He wanted me to feel at home, so he served Kentucky Fried Chicken in the original boxes. And of course I was looking forward to good Egyptian food!

AM: Some things don’t change! What kind of architecture interests you now?

FB: I don't follow architecture anymore. What little I've seen lately makes me think too many architects are trying to be different just for the sake of being different. I'm much more interested in great architecture of the past.

Bookhardt has little regard for contemporary architecture but counts Antoni Gaudi's Casa Batlló in Barcelona among his favorite buildings.

AM: Do you have a favorite building?

FB: Just about anything by Antoni Gaudi. What an incredible imagination! I love Casa Batlló in Barcelona, especially its details. Gaudi shaped the balconies to look like masks. He was hired solely to design a new façade, so the façade he created became a symbolic “mask” over the original building.

And I have a special place in my heart for the many old buildings of New Orleans, especially my house in the Marigny. It was finished in 1867, just after the Civil War. As a college kid at Tulane, I visited a similar Greek Revival house in the Garden District. I was really impressed with it and thought to myself "one day..."