Last Call: “Self-Taught, Outsider and Visionary Art from the Permanent Collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art"

Thornton Dial, Struggling Tiger in Hard Times, 1991. Oil, rope, tin, carpet, and industrial sealant mounted on a wooden panel. Courtesy the artist and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

Earlier today, Emily Wilkerson reviewed "Her Infinite Variety" with an eye to its curatorial framework. In another approach to thinking about exhibition context, Tori Bush reviews “Self-Taught, Outsider and Visionary Art from the Permanent Collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art," also on its last weekend.

Over 10,000 visitors attended February’s Outsider Art Fair in New York—triple the number from the previous year. While many in New Orleans may have missed this extensive fair, there is still time to catch the panoptic “Self-Taught, Outsider and Visionary Art from the Permanent Collection” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. Dusting off pieces rarely shown and in some cases never before made public, the exhibition is impressive in the sheer number of artists included, 42 in total. Rarely does an exhibit pay such expansive homage to the many artists who have been dubbed “self-taught,” “outsider,” or “visionary.” However, it is because the works are so numerous and diverse that the question naturally arises, how or why does an artist come to be defined in these terms?

Indeed the roots of these terms are deeply fraught, each one calling from different time periods and practices. Historically visionary art has often referred to the subject matter of the works, which includes images of a spiritual or religious nature. Self-taught is a term both broad and vague: What artist is not self-taught in some way? Outsider art, however, can be seen as the patient zero of this discussion.

The category of outsider art can be traced back to Art Brut, a genre that originated from Jean Dubuffet’s intrigue with European psychiatric writings on the artistic output of institutionalized persons. Art Brut, which literally means raw or rough art, came to refer to creative work made outside the established art scene by those such as psychiatric patients, prisoners, and children. In 1972, British historian Roger Cardinale published a book, Outsider Art, which heavily informs the current use of the term. Outsider Art, for Cardinale, was not indoctrinated with “a cultural ideal that is untouchable, inalterable, based as it is on the unshakable belief in such things as ‘our cultural heritage,’ ‘the legacy of the past’ and the fetish of the great masterpiece.” Cardinale clarifies what outsider art is not more than what it is.

One of the many problems with this term “outsider art” is that it does not refer to any particular unified aesthetic or theory. In its most generous usage, the only unifying point is that each artist is working to create a highly personalized and individualistic visual account of the world. For some curators and art historians, the term “outsider” has become simple shorthand to encapsulate a large group of disparate artists, but we must acknowledge that the term tends to group together already marginalized artists.

Almost three-quarters of the artists in the Ogden’s exhibition are people of color. While critical, curatorial, and historical precedents have codified these artists into the genre, maybe this term has outlived its use, revealing the carefully constructed art world that separates those that belong from those that don’t.

Reverend Howard Finster and Thornton Dial are both exemplary creators of art, one a white Baptist Reverend from Georgia who at age three saw his first vision of God, the other a black farmer and factory worker from Alabama who spent a lifetime working with found objects to expand upon the yard art traditions he saw around him. There is little that connects these two artists aesthetically or conceptually. Finster was an intensely prolific painter of angels, leopards, UFOs, and clouds. Dial creates large, physical pieces made of things like driftwood, barbed wire, scrap metal, and dead birds that comment on contemporary issues of politics, race, and death. These two artists’ works are intensely specific to their own worldviews of aesthetics and practice, and united perhaps only by an aeonian creativity and eccentric soul.

So the question is: How will curators and art historians work to reposition artists that have been marginalized into (or outright excluded from) a canon that objectively builds links between creators along basic binary lines? As outsider art gains increasing market and critical attention through events like the Outsider Art Fair and national exhibitions, now is an important moment to examine a more respectful context in which we can discuss these works.

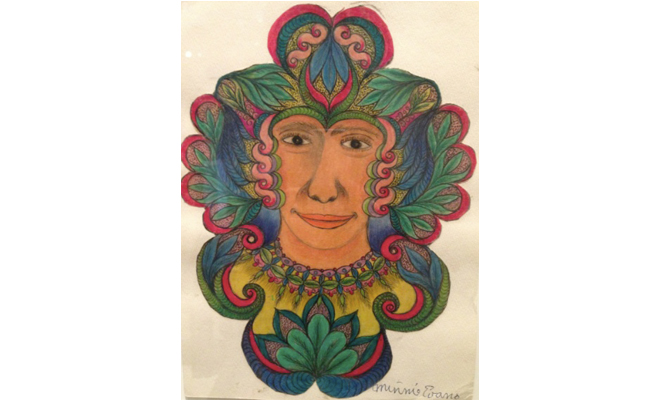

Minnie Evans, Untitled, No date. Colored pencil and ink on paper. Courtesy the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

“Self-Taught, Outsider and Visionary Art from the Permanent Collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art" on view through April 7 at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.