Last Call: ''More Than a Game'' at Tulane University

Installation view of a Newcomb gym uniform, c.1909, in ''More Than a Game'' at Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

It’s the last weekend to catch ''More Than a Game'' at Tulane's Newcomb Art Gallery. Before it's gone, Nick Stillman reviews.

As much as enthusiasts of each try to force a connection, sports and art just aren’t equivalents. Sports are not inherently art (though the transcendence occasionally does happen). Likewise, contemporary art rarely possesses the immediacy or broad appeal of sports (there are exceptions here as well). The current (Western) sporting world bears little of the countercultural proclivities that defined it in the 1950s and 1960s. Art, however, has retained these attitudes as the foundation of its identity--much more so than opticality--since modernism. For all its rhetoric and supposed good intentions regarding inclusiveness, the contemporary Western art world is far less diverse along lines of class and race than major college or professional athletics. That said, the visibility of gender diversity in the art world is much more apparent than in sports, where if one doesn’t live near the universities of Tennessee or Connecticut, one may be totally unexposed to women’s athletics beyond a SportsCenter blip of grunting tennis players or Danica Patrick. And a Google image search for “Danica Patrick” reveals that she isn’t revered exclusively for her ability to drive a car.

So the very existence of "More Than a Game: Sports and Identity at Newcomb and Tulane" stirred some anxiety in this follower of both art and sports. Much like crafts a generation ago or comics prior to that, sports are rarely considered legitimate material for consideration in contemporary art. Unlike the domains of crafts or comics, sports did not (and do not) require the lessons of postmodernity or the endorsement of the museum to acquire visibility or legitimacy. Curator Sally Main mostly averted the question of how and when sports and art merge, and instead fanned out a diverse and not necessarily related array of materials touching on the culture of athletics at Tulane and Newcomb (the former women’s college, now absorbed by Tulane).

All of the drawings on display are sourced from Tulane’s collection of work by New Orleans illustrator John Chase (1905-1986). A professor of New Orleans history at Tulane, of cartooning at UNO, and the cartoonist for the New Orleans Item-Tribune, the States-Item, and several college football teams, Chase is primarily represented by gouache drafts of cover illustrations for official college football game programs. All of these depict some version of a shared theme: a wily Tulane-affiliated rascal dupes the various gullible/moronic mascots for the estimable teams Tulane football faced in the 1950s and 1960s (LSU, Alabama, Auburn, Texas A&M).

Drawings presumably ticketed for inclusion in newspapers have predictably wider political implications. The 1970 drawing Thanks, Sugar Bowler, for example, shows a smugly satisfied man burning a “sugar mortgage” in the Sugar Bowl trophy while a thrilled Louisiana representative thanks him for the inspiration and makes off with a sky-high stack of bonds for a “Dome Stadium.” Bonds for the impending Superdome passed for construction in 1966, but the dome wasn’t completed until 1975, three years after the targeted ribbon-cutting, eight years after the Saints joined the NFL, and a year after New Orleans hosted its first Super Bowl . . . at Tulane. A police investigation into criminal financial negligence went nowhere.

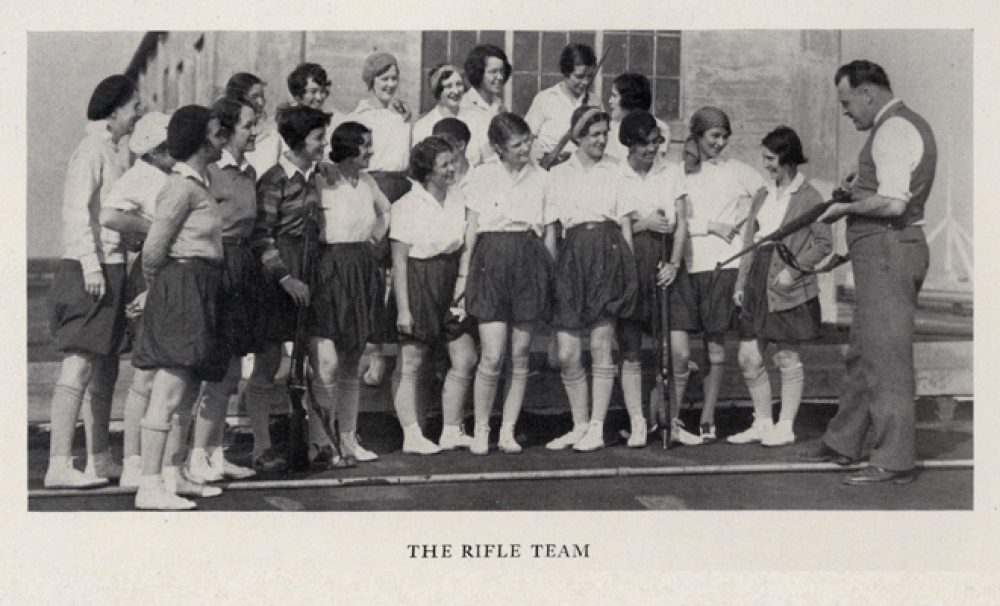

Less explicit, but no less political, is a room featuring photographs (unfortunately almost always digital enlargements of the originals) and archival documentation relating to the history of women’s athletics at Newcomb. Many of the photos are of the yearbook variety and originally appeared in Newcomb’s annual Jambalaya. A 1923 image, for example, shows a group of ladies in skirts negotiating a draconian indoor jungle gym. A 1920 action photo of basquette ball--a game invented by the school’s initial instructor of physical culture, Clara Gregory Baer--reveals a healthy crowd of spectators compared to other game shots, despite its prohibition against two-handed passing because it “compressed the chest.” A team shot of the sweetly smiling members of the 1926 women’s rifle team is bizarrely incongruous, and a 1942 photo titled Resting After P.E. Class, which shows four relaxed women presiding over what initially appears to be 17 corpses on stretchers, is thoroughly haunting in its Holocaust connotations.

Perhaps the most relevant similarity between sports and art cultures is a reverence for lineage, a yearning for clarity in the present through the purities and misgivings of their respective pasts. If the current state of art can be characterized partly by a hyperawareness of its history, sports operate on a similarly informed plane. In that regard, "More Than a Game" could have used additional context about the specific issues (stadium financing, vastly different receptions for sports based on which gender was playing them) it hinted at--and those it didn’t. The topic of race, for one, went conspicuously unmentioned. And while it was entrancing to see the strikingly Constructivist Newcomb Gym Uniform from 1909 draped on a life-sized mannequin, a visual presentation of the evolution of Newcomb athletic uniforms from the turn of the century to the present would have been a useful indicator of how feminism affected the nature of what constituted acceptable dress for women’s teams in the South. "More Than a Game" afforded some idea of what a century of Tulane and Newcomb athletics looked like, but little in the way of why it mattered.

Photographer Unknown, Newcomb Rifle Team, c.1926. Digital image from a 1927 Jambalaya yearbook. Courtesy the University Archives, Tulane University, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

"More Than a Game" on view through September 15 at Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University, New Orleans.