Last Call: Monica Zeringue at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery

Tomorrow is the last day to catch Monica Zeringue's “Goddesses and Monsters” at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery. Before it's gone, Taylor Murrow reviews.

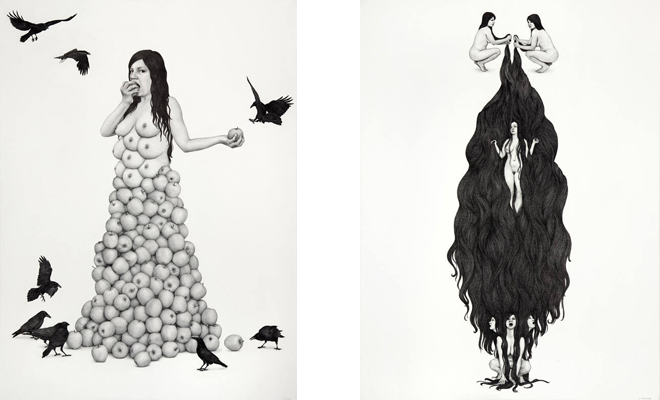

Monica Zeringue, Zeus´ Garden, 2013 (left) and Ophelia Descending, 2012 (right). Both graphite on primed linen. Courtesy the artist and Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, New Orleans.

Monica Zeringue

Jonathan Ferrara Gallery

400a Julia Street

April 1–23, 2013

The allegorical nature of mythology is the core of its appeal: myths function as narrative examinations into philosophy, faith, and science. They offer ways of understanding the breadth of the human psyche—cruelty, passion, desire, and revenge. Myths engage us precisely because they reveal aspects of human nature, portraying deities and men embattled in the highest of moral struggles. In "Goddesses and Monsters," Monica Zeringue constructs her own visual legend using elements of Greek and Roman mythology—mostly the labors of Hercules—as departure points for her signature self-portraits. Zeringue’s drawings, expertly rendered in graphite on linen, have often depicted the artist mid-pubescence, but the selves in "Goddesses and Monsters" have physically matured. Now the artist casts herself as heroine and villain, as beast that needs to be captured or slain and the one who aims to destroy it.

In Zeus’ Garden, 2013, she is the embodiment of fertility, mammalian and fruit bearing, a hybrid female whose nine overlapping breasts descend into a pile of apples. In Cerberus, 2012, she is the three-headed brute, each head open-mouthed and wailing, though lacking the savage animalism we associate with the watchdog of hell. A similar softening occurs in Hydra, 2011, in which the most obvious trace of the ancient sea serpent lies in the depiction of the artist’s seven heads and long flowing hair, curling at the end like a snake’s tail. Hydra is one of two works on display that draw upon Zeringue’s usually prominent hair motif; in Ophelia Descending, 2012, the figures’ hair swirls and cascades like a monsoon dominating the canvas. Whether the river of hair is drowning Ophelia or birthing her is left for interpretation, but as she moves towards the gaping mouths of the women below (another Cerberus nod), the connection between femininity and destruction is established.

Of course, mythology is by no means uncharted territory in art; artists have been offering their own interpretations for centuries. Here Zeringue uses her own image as a vehicle to develop identity through role-play. This feels like an exploration into womanhood—one that an adolescent girl from her earlier self-portraits might embark on, crudely trying on different cloaks to see what fits. The blank space that occupies much of the drawings offers the viewer an entry point into her world, the opportunity to envision a place at the crossroads of the real and imagined where these fabled creatures might coexist. It may be Zeringue’s image that is replicated in so many forms, but she makes room for the viewer to consider his or her own interior journey.

Monica Zeringue, Hydra, 2011 (detail). Graphite on primed linen. Courtesy the artist and Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, New Orleans.