Review: “Patricia Cronin: All Is Not Lost”

Patricia Cronin, Memorial to a Marriage, 2000-02. Carrara marble. Courtesy the artist.

Patricia Cronin

Newcomb Art Gallery

Tulane University

April 25—June 30, 2012

The pursuit of the ideal may no longer be a central concern in art, but for many of us it remains a personal desire. Patricia Cronin’s funerary piece, Memorial to a Marriage, 2000-02, harkens to a neoclassicist sensibility, a deliberate counterpoint to the work’s contemporary political message. The Carrara marble sculpture depicts the artist and her spouse, Deborah Kass, lying nude on a bed draped with a sheet. The two hold each other in a passionate, gentle, and transcendent embrace. Memorializing a relationship in death that was then not fully recognized in life, Cronin’s Galatea was made flesh when she and Kass married the precise day that same-sex marriage became legal in New York.

The sculpture, whose permanent home is the couple’s future gravesite in the Bronx’s Woodlawn Cemetery, is potent enough to stand on its own, but the exhibition unites it with over 60 of Cronin’s watercolor renderings from the series, Harriet Hosmer: Lost and Found. The backdrop of Cronin’s renderings of Hosmer’s work in the adjoining gallery rooms evinces the sculpture as a multilayered feminine discourse on love, sexuality, and death.

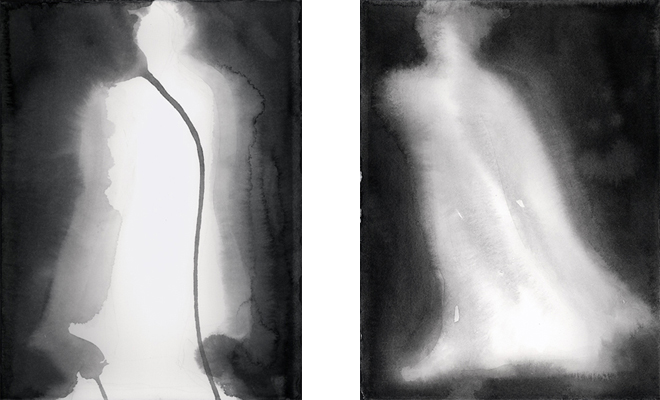

Patricia Cronin, Ghost #16, 2007 (left) and Ghost #21, 2007 (right). Both watercolor on paper. Photos by Rayographix. Courtesy the artist.

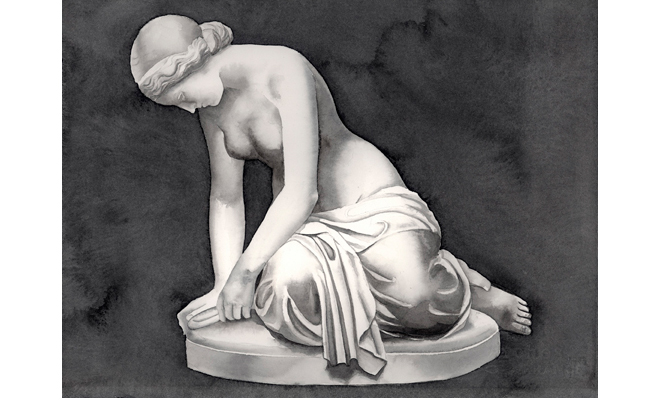

Hosmer is an overlooked, albeit prolific woman sculptor who completed much of her work as an American expatriate living abroad in Europe in the 1800s. Her neoclassical style and traditional subject matter—Medusa, Zenobia, fauns, and cherubs—exemplify the unaffected pursuit of the ideal. Cronin has painted each of Hosmer’s known works in a suite of watercolors so precise that at first glance one might mistake them for photographs. Several of Hosmer’s works have been lost to the ages—their locations are today unknown and their likenesses were never captured. For those missing pieces, Cronin substitutes abstract black-and-white phantasmal outlines of what their forms might have been, each assigned the simple moniker of Ghost and a number, reaffirming their significance in the Hosmer canon.

Cronin’s meticulous simulacrum of Hosmer’s body of work serves as both homage to the artist and conceptual reimagining. Classical and neoclassical sculpture were art forms traditionally dominated by men often visually depicting the female ideal. When a woman is the one behind the hammer and chisel, there is an equalizing effect. Visceral responses to the female form can be universal—a human response, not just a heterosexual response. Same goes for entering into a marriage—a human right, not just a heterosexual privilege.

Memorial to a Marriage sits stoically in its own dark room in the gallery space, bathed in an illuminating glow. The dream-like image of the couple carved pristinely into the white marble eternalizes their bond. Delicate details such as the toes of the two figures touching reminds us that marriage, regardless of gender, is a commitment to lasting love and partnership. The sculpture is essentially Cronin’s version of her ideal—an eternal moment in time between two lovers—but also her assertion that her bond with Kass (much like Hosmer’s work) will outlive both outdated social mores as well as their own mortality.

Patricia Cronin, Oenone, 2006. Watercolor on paper. Photo by Rayographix. Courtesy the artist and the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington; Gift of Lois Plehn.