Round Up: The Best of Prospect.2 New Orleans: Part 3

Installation view of Dawn DeDeaux’s The Goddess Fortuna and Her Subjects ... at The Historic New Orleans Collection's Brulatour House and Courtyard as part of Prospect.2 New Orleans. Photo by Mike Smith. Courtesy the artist.

Dawn DeDeaux

Brulatour House and Courtyard

520 Royal Street

October 22, 2011–January 29, 2012

The moment the sky turns dark is transformative. In the Brulatour Courtyard, it’s the time when Dawn DeDeaux’s perverted portrait of Ignatius Reilly comes to life, converting the romanticism of the historic courtyard into the dark imaginings of John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. Those familiar with the iconic New Orleans novel will recognize central elements from the narrative in this installation. The Levy Pants revolution, the Lucky Dog cart, and Reilly’s hunting cap all make appearances; while Reilly’s slovenly bed occupies center stage of the courtyard, fountain spewing from its center.

DeDeaux pairs Toole’s famous imagery with a rich symbolic language of her own: white death masks and red pantaloons figure prominently. Robert E. Lee’s Civil War boots and white camellias recall the Confederate South. Robed mannequins in dunce caps on the surrounding balcony—a disturbing confederacy of dunces—bring to mind visions of the occult, looming with a sinister Klan-like presence.

In the novel, masturbatory Reilly, always spiteful towards the dunces of the outside world, is fixated on the goddess Fortuna, regularly invoking her in his long-winded philosophical dialogues. DeDeaux’s Fortuna takes form with full cosmic force as New Orleans sissy bounce artists Big Freedia and Katey Red. Masked and in surreal costume, accompanied by their attendant dancers, they float and gyrate to a bounce track, spinning their wheels of fortune. DeDeaux, known for her pioneering use of digital media, further tricks out the experience, manipulating projections and reflections to give the illusion of a hypnotizing Fortuna performing at the foot of Reilly’s bed, taunting onlookers. Her voyeuristic investigation into the fetishism and confusion of Toole’s novel utilizes seemingly every space in the courtyard to provide a one-of-a-kind sensory experience, extracting viewers’ own latent sexuality and fear, and heightening them to haunting effect.

—Taylor Murrow

Nick Cave's Soundsuit, 2006 (left), and Soundsuit, 2009 (right), on view at Tulane University's Newcomb Art Gallery as part of Prospect.2 New Orleans. Photo by James Prinz. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Nick Cave

Newcomb Art Gallery

Tulane University

October 22, 2011–January 29, 2012

Ashton Ramsey

Ogden Museum of Southern Art

925 Camp Street

October 22, 2011–January 29, 2012

Nick Cave’s five Soundsuits on display at the Newcomb Art Gallery may disappoint Cave fans. The suits are older, from 2006 through 2010, and are neither displayed as vignettes nor accompanied by performance videos, as they frequently are. When in use on stage, Cave’s painstakingly detailed textile sculptures conceal the wearer’s identity, trading the apparent markers of race and gender for a visual cacophony of heavy beading, embroidery, and organic materials such as twigs or human hair. Although Cave continues to create and display new Soundsuits, the five on view offer a worthwhile introduction for those unfamiliar with his work and a striking visual and conceptual complement to Ashton Ramsey’s jubilant handiwork across town at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

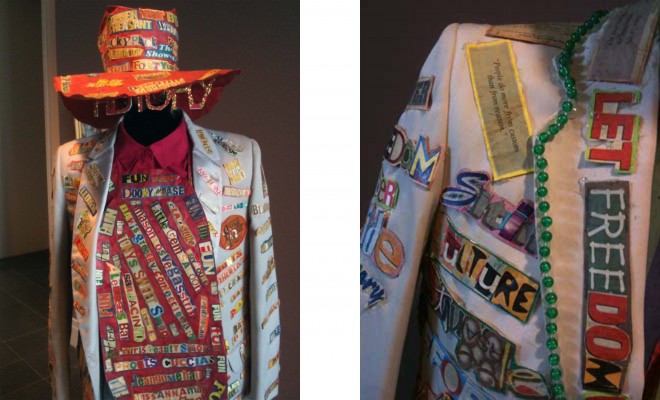

A New Orleans native, Ramsey began creating his suits, like the five on display at the Ogden, as an alternative to expensive and time-consuming Mardi Gras Indian suits. In lieu of beads and feathers, Ramsey glues cutouts from magazines, newspapers, and other print materials to men’s suits, which he wears to all manner of local events, not just Mardi Gras. The suits include personal artifacts such as press clippings and portraits that celebrate Ramsey, as well beloved African-American and New Orleans traditions: collaged tributes to important community figures like the late Ernie K-Doe or his “History” suit, which highlights local businesses like Dooky Chase.

While the lack of context in Cave’s exhibition detracts from the pieces, Ramsey’s suits are enlivened in the stark museum setting where they are without the distractions of the street, allowing for more individualized attention. Both sets of suits, however, find additional meaning in relation to one another, speaking to the myriad ways in which existing traditions of Mardi Gras function as visual culture both in New Orleans and beyond. But Ramsey’s show is undoubtedly the more compelling of the two, one-upping one of the key attention-getters of P.2.

—Amanda Brinkman

Ashton Ramsey's suits on view at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art as part of Prospect.2 New Orleans. Courtesy the artist.