A Lost World: “Storyville: Madams and Music” at The Historic New Orleans Collection

For our “Queer Tropics” editorial series, Ashley L. Voss looks back at last year’s exhibition at The Historic New Orleans Collection exploring New Orleans’ infamous red-light district.

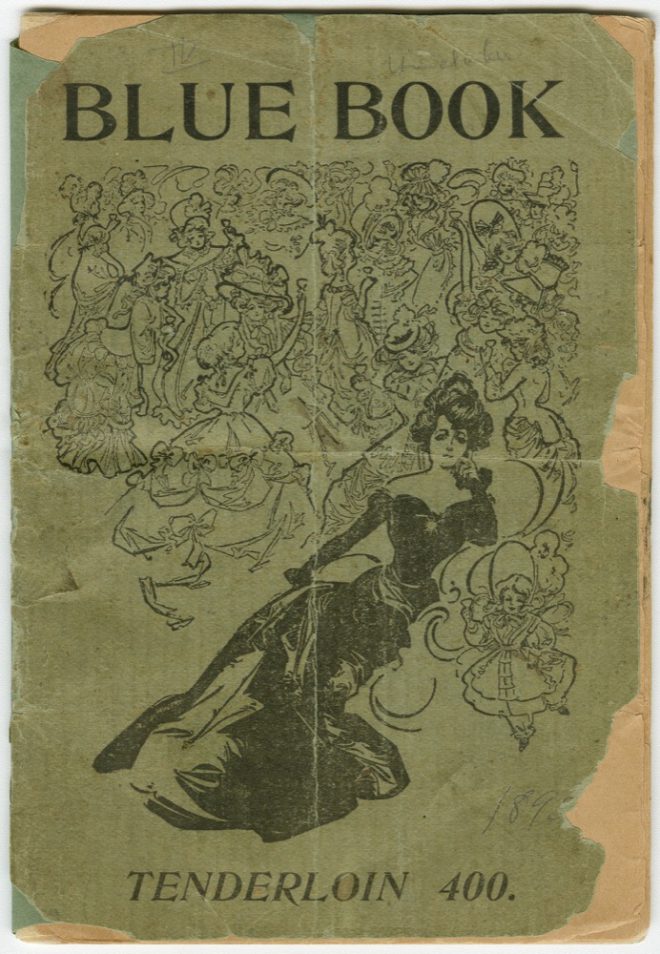

A 1901 Blue Book. Courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In January 1897, The Times-Picayune announced the passage of an ordinance by the Mayor of New Orleans stating, “...from the first of October, 1897 it shall be unlawful for any public prostitute or woman notoriously abandoned to lewdness to occupy, inhabit, live or sleep in any house, room or closet situated without the following limits….” This new restriction bound prostitution to a district—dubbed “Storyville” after city councilperson Sidney Story, who proposed the act—with an area of ten square blocks.

“Storyville: Madams and Music,” on display last year at The Historic New Orleans Collection (located just blocks away from the historical Storyville neighborhood), shared the lives of the madams who operated upscale brothels and the jazz music that evolved amidst the debauchery of New Orleans’ red-light district from 1897 to 1917.

Conveniently bordering the north side of the Southern Railway terminal, Storyville’s most elaborate Victorian mansions (the Arlington, Mahogany Hall, and the Star Mansion) paralleled the tracks to lure train passengers into the district. Their architecture now recalls a time of lust and luxury—decadence disguising corruption. Not unsurprisingly, living conditions for the prostitutes worsened the further away they were located from the railroad.

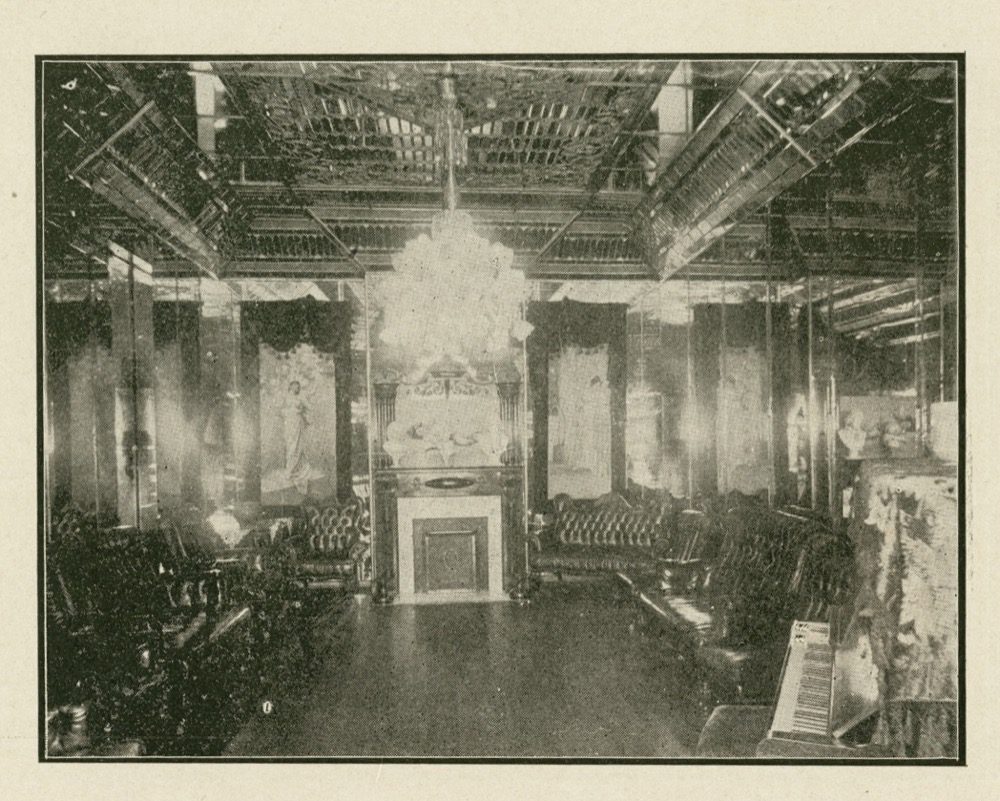

Visitors used editions of the so-called “Blue Book” and alternative guides to navigate the neighborhood and browse offered services, and many of these texts were on view at THNOC, giving a peek inside these storied bordellos. Extravagant bedrooms and plush seating areas are revealed in a Blue Book from 1908, showing interior views of the Arlington. Grand chandeliers illuminate the detailed drapery—creating an ostentatious playground for desire. Such attractive photographs were used to entice curious readers through the brothels’ doors.

Unofficially known as the “mayor of Storyville,” businessman and politician T.C. Anderson represented the district in the Louisiana House of Representatives. Anderson was well aware of the money Storyville generated for the city and his portrait was even featured in advertisements for several brothels. Ads for Budweiser, private-detective agencies, and funeral furnishings are also found within the bindings of Blue Books. One 1900 advertisement for a medicinal lotion reads, “Marvelous Success with Gonorrhea and Gleet, CURES IN 3 DAYS.”

These books were so influential that madam Lulu White published her own “Red Book” to control the content and attract more clients to her own Mahogany Hall. She was aware of the benefits that strategic marketing granted—considering the portrait accompanying her biography in an advertisement listed in her Red Book is not of her. The truth is revealed when comparing this portrait to her mug shot online.

The music room in Josie Arlington’s Storyville brothel, from a 1908 Blue Book. Courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Adjacent to Storyville, which was situated in the Faubourg Tremé, was a lesser-known district for African-American patrons called the “Uptown” or “Black Storyville,” near today’s New Orleans City Hall—with its own cabarets, dance halls, and saloons. Though jazz music was of course played outside of the districts, these areas allowed for more improvisation and freedom for musicians to explore, fostering much of the day’s now iconic music. The best featured musicians (typically piano players) were known as “professors,” since they had to be prepared to play anything for customers upon request. The lower-end bordellos had mechanical players and hand-cranked gramophones.

Even before the 1917 recording of the first jazz record ever, the musicians who were playing Storyville and who contributed to the development of New Orleans jazz performed across the country. The exhibition at THNOC included photographs of acclaimed musicians Tony Jackson, Ann Cook, and Jelly Roll Morton. A 1947 article by Louis Armstrong in True: The Man’s Magazine describes his upbringing in the Uptown district, where he began playing to prostitutes in gritty honky-tonks. In addition, an advertisement for Original Dixieland Jass Band’s originating recording was displayed beside the record itself.

To provide a contemporary connection, the movie poster and original screenplay for director Louis Malle’s controversial film Pretty Baby (1978) were on display. The film shares the story of a naïve 12-year-old girl, played by an equally young Brooke Shields, beginning to work in one of Storyville’s ostentatious brothels.

“Storyville: Madams and Music” included an assortment of portraits to tell the history of the district itself, evident in the inclusion of a photograph of Willie Piazza, a successful madam condemned by the city for promoting interracial sex. At the beginning of World War I, federal officials sought to close Storyville in order to protect soldiers from venereal infections, and in an attempt to save the district, local politicians declared a city ordinance on February 7, 1917, proposing Storyville be formally segregated and “restrict prostitution by women of color” entirely to the Uptown district. At that time, Piazza was asked to shut down her upscale brothel and relocate. In a fight against racial segregation, Piazza filed suit alongside other women of color to protect integration in Storyville and surprisingly won.

However, the victory was short lived as federal officials forced Storyville to close later that year, when a naval base was stationed along the Mississippi—as “vices” were not allowed to be within five miles of a military base. This news impacted all of Storyville as everyone had to relocate and brothels had to sell their furnishings—and even had to fight the city to receive minimal money for their land. A 1909 auction notice from Mahogany Hall lists the items for sale, including 500 mirrors, six superb crystal chandeliers, eight ice boxes, gold mantel cabinets, and the list continues.

The Original Dixieland Jass Band’s Dixieland Jass Band One-Step/Livery Stable Blues (1917), considered the first jazz record. Courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Storyville was demolished in 1936 to construct homes for low-income families through the United States Housing Act of 1937. At THNOC, photographs from the 1930s depicting the exterior of a brothel were displayed next to photographs from the ’40s of the Iberville Housing Projects to illustrate the dramatic transformation of the neighborhood. Surprisingly, a stained glass window from Mahogany Hall was found intact amongst the construction rubble—and White’s legacy continues to seduce through its multicolored panes.

“Storyville: Madams and Music” did little, however, to describe the living conditions for the women working in the brothels, with only one reference to them in a photograph from 1910. This haunting image consists of a three-by-three grid of portraits of women who worked in the district. A number is scribbled atop each grim expression as an identifier, suggesting anonymity and exploitation. In contrast, two photographs from 1912 of prostitutes lounging comfortably in classical odalisque positions seemingly glorify the lives of these working women. One wears a playful mask while posing for renowned Storyville photographer Ernest J. Bellocq. For these women, life appears to be filled with leisure and luxury.

Ultimately, the exhibition didn’t say much about how these women felt about their lives of sex work, and a more comprehensive, and complicated, description about the personal lives of these women is needed. What were the lives of the working women like? Perhaps this documentation is lost―but until revealed, their stories are to remain in the whispers of contemporary visions of Storyville, forever subservient to the shadows of their profiting madams.

By choosing to revel in the glamour and jazz that lived within the walls of the upscale brothels in Storyville, THNOC fulfilled its mission to give a peek into the district’s legendary history. But it left viewers to complete the story themselves. To quote Pretty Baby’s Madam Nell, who fondles a plump cigarette, “There’s only two things to do on rainy days, and I don’t like to play cards....”

Editor's Note

“Storyville: Madams and Music” was on view April 5–December 9, 2017, at The Historic New Orleans Collection’s Williams Research Center (410 Chartres Street).