Every Drop of Blood: Healing Trauma Through Art

Denise Frazier looks at two attempts to use art to capture the experiences of veterans who have returned from service—including a recent project by Goat in the Road Productions in which she performed.

Jeremy Guyton, Leslie Boles Kraus, Dylan Hunter, and Darci Fulcher in Goat in the Road Productions’ Foreign to Myself, 2017, at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. Courtesy Goat in the Road Productions, New Orleans. Photo by Joshua Brasted.

“I want to be very deliberate and specific about what I work on. I don’t want to feel like I am wasting my time. So, when I decided to curate shows for veterans, I wanted it to be for specific reasons, not to make people feel good or to feel better in art,” articulates Ariel David, veteran, curator, and executive producer of the Of Eden project. The initiative, which consists of a documentary and an exhibition, seeks to “create an opportunity for a visual dialogue”—a method of storytelling that includes the work of veterans to share what they consider the “less heard perspectives” on military service and war. The exhibition, “Of Eden: A Visual Dialogue of War,” ran last fall at the International House hotel in New Orleans, and the project is part of what David considers a larger trend of intersectional thinking between health, clinical services, and the humanities.

David’s own perspective draws from myriad experiences that include braving combat zones and swimming in Saddam Hussein’s pool to earning a graduate degree in public health and making art with her young daughter. When asked about the significance of art and the military in her life, she asserts that intention and knowledge are the reasons she curates exhibitions on war trauma. “People disagree on what defines art. It doesn’t count as art until someone buys it or uses it or, essentially, consumes what you create. I don’t really see myself as an artist. I see myself as a writer. I write a lot about my experiences in deployment and in the military,” states David. Storytelling through art is a prominent feature in “Of Eden.” Most civilians are familiar, at least in an abstract way, about the challenges that veterans face, but art makes the stories more visceral, more identifiable, and more real for people living in the United States, a country largely geographically distant from the wars of the past century.

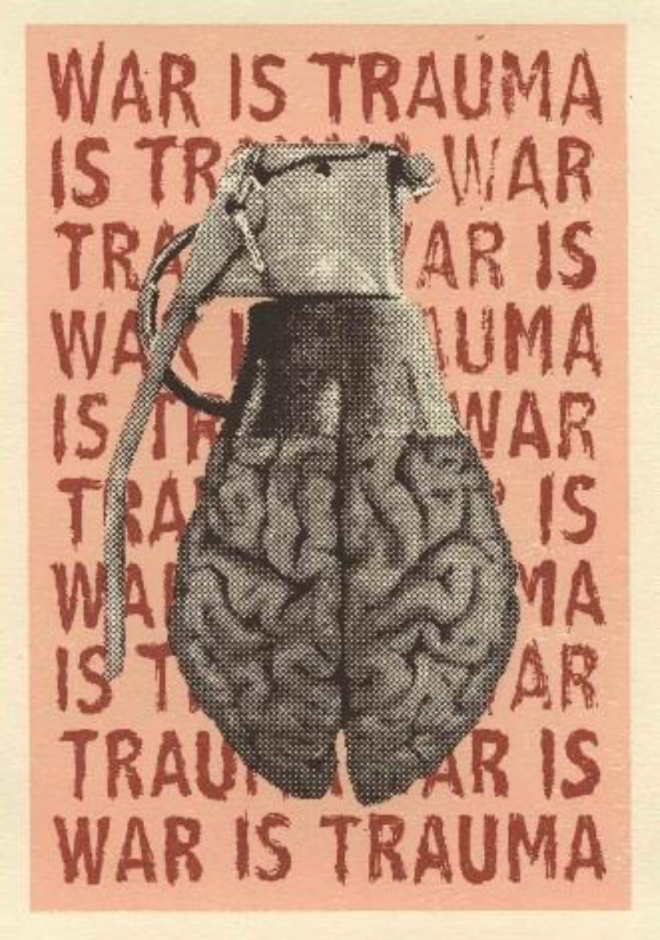

Artist-veterans have sought to dispel and disquiet the myth of war as something that one leaves behind upon returning home. If the artwork in “Of Eden” teaches us anything, it’s that war-induced trauma has no borders, no boundaries, and no walls. For instance, Jesse Purcell’s War is Trauma, 2014, features a brain in the shape of a grenade accented by a light pink background with smeared blood-red lettering repeating the title of the work. The repetitive phrase is reminiscent of propaganda, and the story of a deeper, internal trauma is accentuated by the soft-layered organ depicted as a hardened instrument of death and destruction. The disconnect and paradox of this image is parallel to the trauma and post-traumatic stress that remains enigmatic and amorphous for many veterans and their loved ones.

Jesse Purcell, War is Trauma, 2014. Three-color silkscreen print. Courtesy the artist.

New Orleans-based Goat in the Road Productions’ artistic co-directors, Shannon Flaherty and Christopher Kaminstein also sought to tackle the topic of trauma with their latest production, Foreign to Myself, at the Contemporary Arts Center, in which I performed. The script is based on two years of research that encompassed interviews with Veterans Affairs therapists, doctors, and veterans themselves. David was one of the veterans we interviewed for the show. Like David’s exhibition, Foreign to Myself responds to a need to inform and understand the challenges that veterans face, especially the struggles that don’t leave noticeable physical wounds, like post-traumatic stress. For many viewers, art not only reveals this; it also exposes a certain complacency with war, foreign policy, and mental-health struggles for returning veterans. The show tells the story of Alex, a young woman who comes home from deployment and faces the difficulty of re-entry and of healing herself and her interpersonal relationships.

Flaherty and Kaminstein’s exploration of the topic stemmed from personal reasons. Kaminstein states, “Many of our ensemble members have relatives that have served and there was an interest in exploring the topic, and the difficulties encountered by servicemen and women coming back from war. In particular, we were interested in looking at questions of civilian versus military identity.” On March 25, Goat in the Road, in partnership with the Veterans Arts and Humanities Alliance and the Contemporary Arts Center, produced Get Your Art On, a community event that featured the Combat Paper project, an initiative to make paper from military uniforms, a guided meditation space; a display of veterans’ art; and a short reading of scenes from the show.

David asserts that intentionality does more than dispel complacency; it has personally motivated her to incorporate social-justice advocacy and public health into art. “You can have your Fourth of July barbecues and you can go to your Memorial Day events and you can say ‘thank you for your service’ to people as much as you want, but every drop of blood, every person who died, every civilian who died, every military member who died, every drop of blood is on everyone’s hands. I think it’s important to be intentional,” says David. Art gives a voice to the silence surrounding war and trauma. The unchartered territory of the brain and its relationship to trauma have yet to be revealed fully, but thankfully art can navigate through the mystery with intention.

Editor's Note

Goat in the Road Productions’ Foreign to Myself was presented May 18–21, 2017, at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans.