Tell Me I’m Your National Anthem

Charlie Tatum contemplates a vision of America embedded in a painting by Bo Bartlett and Lana Del Rey’s music videos.

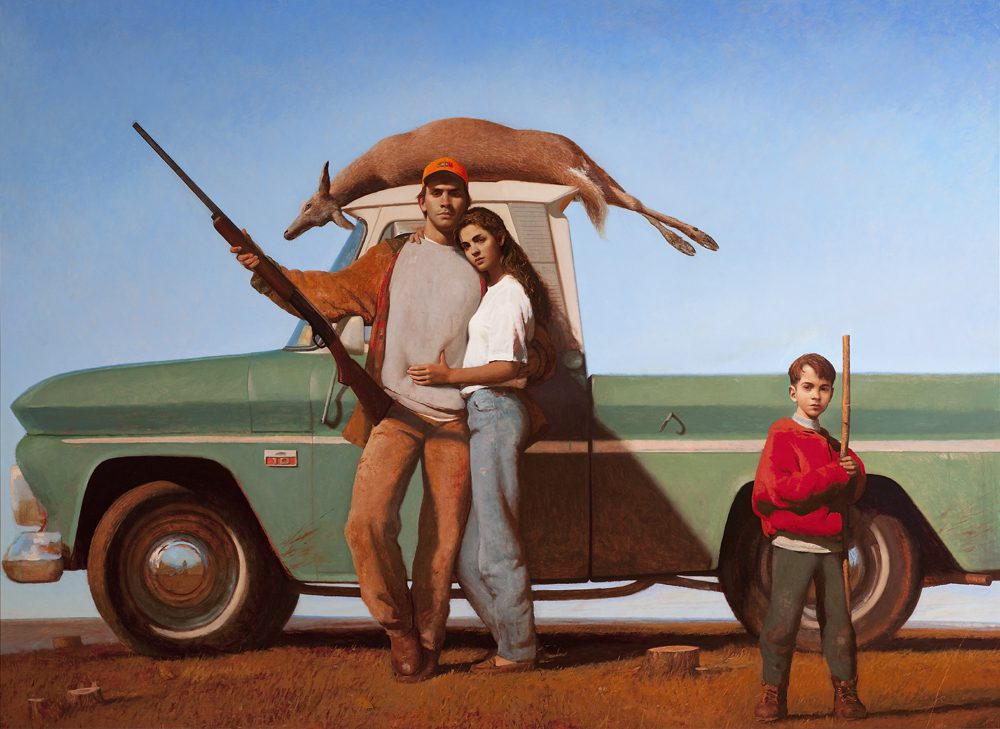

Bo Bartlett, Young Life, 1994. Oil on linen. Courtesy the artist and Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York.

Bo Bartlett, Young Life, 1994: A woman stands at the center of the canvas, in a loose white t-shirt and boyfriend jeans, her arms clutching a tall, rugged man—Carhartt jacket, neon-orange hunting hat, gun propped against his hip. Her left hand sinks into the grey of his sweatshirt, her fingers searching his stomach for the pleasure of muscle. Together they pose in front of a large green pick-up truck in a clearing. A deer is stretched across the top of the truck’s cab, waiting to be thrown in the bed and grilled for dinner or stuffed and placed over the mantle.

The woman’s age is indeterminable. She looks like one of those twenty-something actresses playing a high-school junior on television. Her face glows with young love, young life, young whatever.

Her eyes meet ours and you can almost hear Lana Del Rey—Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?

She even looks like her: the delicately sloped nose, the high cheekbones, the casual yet precise accentuation of her backside, a mix of deviance and seeming naïveté. Though the painting is from 1994, it could easily be a still from Del Rey’s next video, the singer intoxicated by sex, guns, and strong country men as she drives through the American South.

Del Rey’s videos are cinematic and superficial in every way. She’s built her career by adopting the signifiers of characters without committing to any subjectivity beneath. She shifts easily from riding with a biker gang in the desert to shooting down helicopters in her see-through nightie to playing both Marilyn and Jackie O alongside A$AP Rocky’s JFK. Each video is a fantasy, the illusions adding up until they’re substantive—all that’s there—a mythology of a carefree, sexy, rebellious, sometimes rough but always elegant, white America. Del Rey is all of the parts she uses to compose herself. She’s the girl of one’s dreams. She finds strength in her weakness against men—she’s the ultimate sad girl—and luxuriates in the contradictions of youth, beauty, and femininity in the 21st century.

Bartlett’s work is generally filed under the banner of American Realism, a history of artists purportedly getting to the heart of what real American life is. I’ve always been skeptical of Realism. Who’s to say that Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper get at anything more real than Kim Kardashian, RuPaul, and Lana Del Rey? What is real life anyway?

Bartlett himself is wary of the label, stating that his paintings “are a representation of how I am feeling and how I am processing those feelings,” inherently complicating the so-called real with the reality of desire. The characters of Young Life are playing their parts in Bartlett’s and our idyll fantasies—of youth, of white rural life, of an American era past. This particular fiction of America was constructed in celebration of labor, a capitalist bootstrapping spirit, but now it’s merely a distraction, whitewashing a colonial history that has always been here, that will always be here.

But it still can be hard to resist the allure of this dream. In typical American fashion, Lana Del Rey reassembles, revivifies, and remarkets this ideal, infusing it with a sexuality that embraces the deception, the knowledge that this America is gone or was never here to begin with. Our desires and imaginations are propelled by this masquerade and our knowledge of its falsities. Anything we do is necessarily performed. Bartlett’s young lovers are also learning these modes of being and of performing, according to this particular version of America.

Young Life and many of Bartlett’s other works are deeply uncanny, pointing us in all directions to disturb the pervasive sense of pastoral calm. Things don’t quite add up. Though our eyes gravitate toward the young couple, a child glares ominously from the right side of the canvas. He looks like he has just stumbled onto the set. (In fact, Bartlett’s son Eliot ran in front of the camera as the artist was taking a source photograph.) A cut-out window in the bottom center of the painting’s wooden frame literally displays a deer tail, curled up, evoking the luxury and death of fur. Bartlett even mixed deer hair into his paint, adding to the textural illusion. Delicate red letters float at the bottom of the canvas—I, G, N. What does this even mean?

What this painting means, though, is not as important as what it makes us feel. The performance is, as we say, too real, reminding us that the culture that shapes our own identities and desires is constantly being reimagined.

Editor's Note

Bo Bartlett’s Young Life, 1994, is currently on loan to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.