A Space to Dance: An Interview with Tschabalala Self

Ashton Cooper speaks with artist Tschabalala Self about the importance of creating diverse narratives around black female bodies.

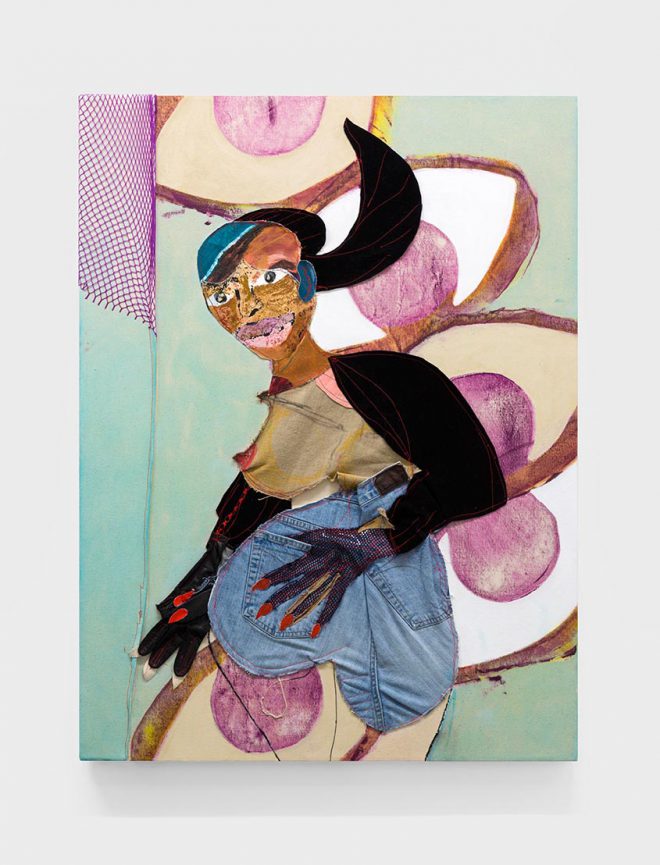

Tschabalala Self, Mira, 2016. Oil, acrylic, paper, fabric, and found materials on canavas. Courtesy the artist and T293, Naples, Italy. Photo by Maurizio Esposito.

Editor's Note

Twenty-five-year-old artist Tschabalala Self splits her time between New York (where she recently had work on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem) and New Haven (where she graduated last May with an MFA in painting from Yale). On March 17, she will debut a new body of work at T293 in Naples, Italy. Titled “The Function,” the exhibition will feature paintings inspired by the long-running show Soul Train, mining that televised celebration of music and dance for its political potential. Ashton Cooper talks with Self about her depictions of the black female body, the characters she creates, and the power of parties.

Ashton Cooper: Your practice has centered around what you term the “iconographic significance of the black female body in contemporary culture and the collective fantasies that surround the black body.” In your artist statement, you say your practice “is dedicated to naming this phenomenon.” Could you outline some of the strategies you use to do this?

Tschabalala Self: I’m depicting the black female body in new ways, where the body is abstracted or exaggerated. I’m seeing how people respond to that imagery and also how that imagery affects me. I feel like everyone’s body signifies something culturally; people’s bodies and appearances are used as symbols and signifiers the same way that language or any other symbol can be used. In my own life, I occupy a black female body and that’s how I identify. It’s always been interesting and important to me to try to understand: what do my physicality and my identity signify to others? And, then, what can it signify? What can it mean? What’s the potentiality of that identity?

AC: You’re looking at how people respond to your imagery. Have there been reactions in particular that changed the way you were thinking or were fruitful for you?

TS: I’m kind of stubborn in the way that I feel about the imagery I’m using. I do find people’s reactions interesting, also sometimes shocking, but usually other people’s reactions to my figures, my characters, don’t change my political ideas. It just gives me more of an idea of the political climate and the social climate in which I’m working.

The main thing I’ve noticed is that when people are confronted with the black female figure or any kind of person assumed to be living a marginalized existence, they expect any story being told about that person to be about their pain and suffering. If you try to explain that an image is about self-love or self-appreciation or joy or happiness in occupying their body, it’s difficult for people to wrap their heads around. That’s always been frustrating for me because it makes me think that most people imagine that women, especially black women, live in perpetual sorrow, heartache, or fear, and I think that’s how people treat black women. If you already believe that someone is living a horrible life and think badly of themselves, you don’t feel guilty treating them poorly or patronizing them.

AC: So a big part of creating these specific characters—whom you name and create narratives around—is humanizing your figures and the women you’re representing?

TS: I want my characters to have problems that are outside of their gender or race. Problems that are universal: heartbreak, grief, loss, desire. And also joys, pleasures, excitement. I think it’s important to show that because a lot of times characters that are based on black women are two-dimensional. There’s plenty of space for them to exist in a social realm or comment on political issues. But there’s no room for ennui or boredom, the boredom of living within these social constraints that define your physical form. What about the metaphysical form, the spiritual or psychological form? Everyone has those dimensions in their mind, in their body.

AC: Are the stories mostly just for you in your own mind?

TS: Usually I imagine or come up with the stories. I’ve recently begun writing down different anecdotes from my own life—like if I have a strange day. I watch a lot of films and read a lot of books so I borrow from those as well. Also, just observing people. I spend half my time in New Haven and half my time in New York. Being around people in New York, being on the train, observing people, overhearing conversations—those are other ways I gather information. I also have three older sisters.

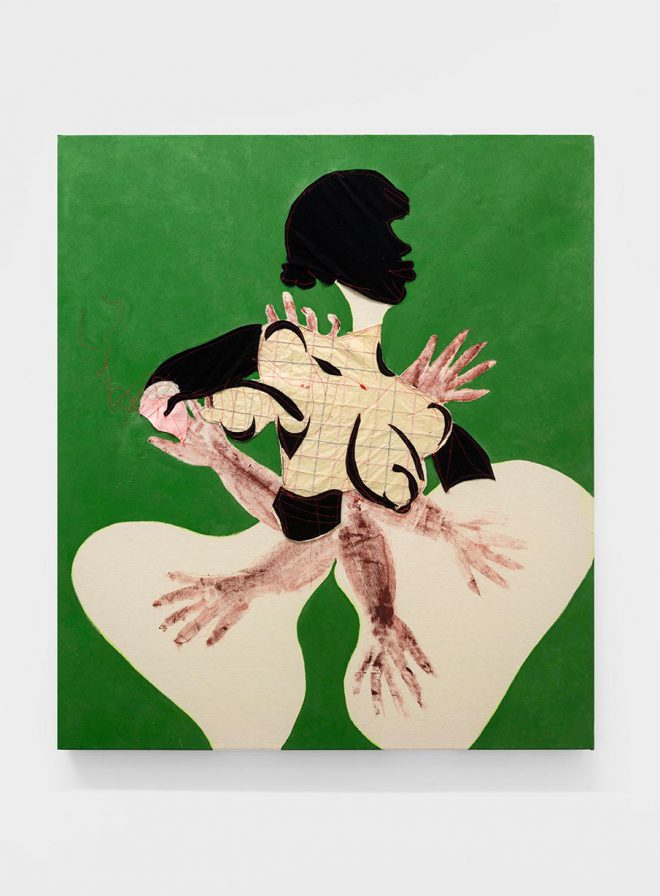

Tschabalala Self, Get It, 2016. Acrylic, Flashe, handmade paper, and fabric on canavas. Courtesy the artist and T293, Naples, Italy. Photo by Maurizio Esposito.

AC: In this new series you’re showing at T293, you’re depicting different figures inspired by Soul Train. Are these also characters that you can invest with different stories or personalities?

TS: Soul Train is the conceptual basis for the exhibition The people on the show are so dynamic in their movement and how they’re expressing their personalities through their dress. Seeing the way people dance amongst each other, the way people compete, the way people flirt, it’s the perfect opportunity to imagine their stories. Also, Soul Train is like a glamorized, televised version of a house party. All parties are great places to imagine stories among people. Anything could happen—there could be a fight, you could fall in love, see an old friend. With this exhibition, the environment I’m creating is trying to get that feel of a house party. I want all the different elements to be interacting the way people would interact at a party. Some of them are going to be very tightly connected and some will be separated, but it’s all going to occupy the same space and they’ll all be sharing a moment together. In a lot of the paintings, the figures are caught mid-motion, like a snapshot.

AC: Dancing is such a specific bodily experience. In your artist statement, you quote Mary Douglas’ Natural Symbols, which says that “the social system places limits on the use of the body as medium.” It’s interesting to think of dancing as existing within that concept but also potentially as a way to be liberated from a social system.

TS: I think that when people dance and how people dance can be a way to fight back. Even if you think about the “showtime” subway dancers, that’s a way of defying social space. Often people on the subway forcibly ignore the dancers; it’s overwhelming for them to engage or acknowledge that kind of liberation. Others are really excited about it. I think that’s one way to see how dance is related to social space. Dance is a way to bring people together and elevate their moods like at a party or even a recital for children. You can also think about how people move their bodies, how people walk, just general movement, and what body language can communicate. How can I express things about the characters’ intentions or personalities through their gestures and the ways that they’re holding their bodies? Especially with black bodies and female bodies, what you do with your body and what you’re allowed to do with your body, especially in terms of dance, can be liberating or absolutely not liberating.

AC: Soul Train started shortly after the Civil Rights Movement was winding down. Did you watch the show as a kid?

TS: The show started in 1971. I was born in 1990. I got the newer version of it. I’ve seen the original on the computer, but I never watched that one on television. One thing that distinguishes the show, coming after that phase of the Civil Rights Movement, is that it was outside of a lot of notions of respectability politics. It allowed more room for creativity without the all-seeing eye of white judgment. There’s freedom to just be without thinking about appropriate representation or appropriate behavior. That’s very important to the show and very important in my practice. If you’re dealing with respectability politics, you’re dealing with people pandering to white supremacy. Soul Train is blackness for blackness’ sake, and doesn’t attempt to explain or justify blackness to white society.

AC: Most of your work has been centered on the female form, but, in this new series, you are including male-female pairs. Is this the first time you’ve done that? Why choose this moment to get into these new images?

TS: The only other time was when I was doing a project during a residency at the American Academy in Rome. l used both male and female models then. For this new work, it came naturally. I was working, pulling from studio scraps, and had an old portrait of my uncle and I wanted to use it. It really fit with the female character I was building. I decided just to go with it.

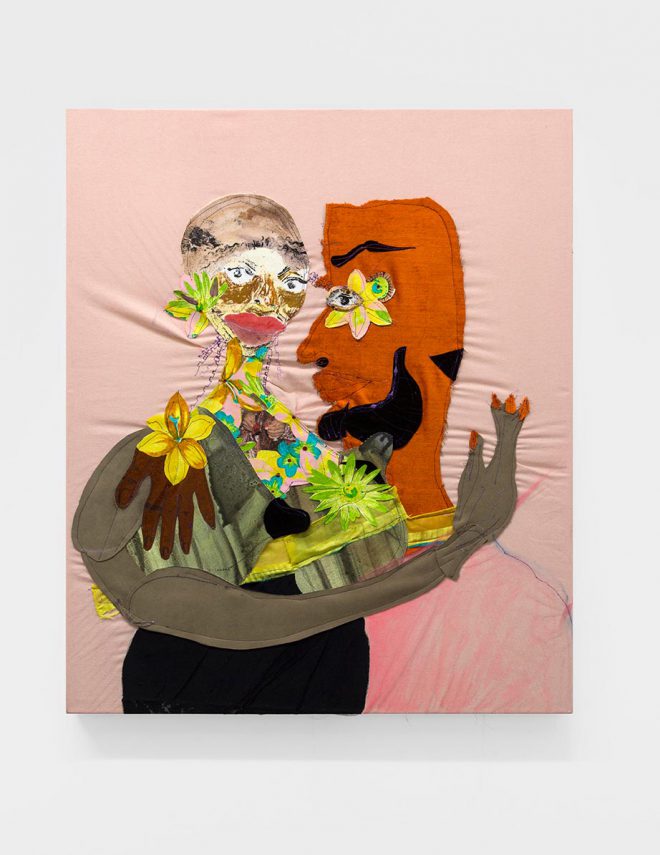

Tschabalala Self, Partners, 2016. Oil, acrylic, charcoal, paper, and fabric on canavas. Courtesy the artist and T293, Naples, Italy. Photo by Maurizio Esposito.

AC: Your process involves finding scraps so that old pieces often get reworked into new ones. Some artists feel a preciousness toward completed artworks but that’s not at all how you approach your practice.

TS: I keep all scraps from everything, and I bring in personal scraps. My mother collected a lot of African fabrics and, when we were little, she would make dresses for us, pillows, and curtains. I have fabric from my family home that I use. I use my old clothing. I use all my old paintings, old works on paper. I keep all of that stuff and just keep reusing it. Even things that are finished; if I come back to them a year later and I think they can be better, I’ll cut them up and reuse them again.

AC: So, in the Soul Train installation, apart from the male figures in the paintings, there is a sculpture of a male character who is made of mirror pieces. Does this relate to what you call the “voyeuristic tendencies towards the gendered and racialized body”?

TS: The mirrored man is a flat sculptural cutout of a male silhouette, and he’s a voyeur in the space. Maybe in a party situation, he would be a wallflower. He’s there to look at and observe everyone else’s actions and movements. This character is a mirror, so, if you're a viewer in the space, looking at him, you also see yourself and all the other works.

AC: We’re supposed to think of art spaces as neutral, white boxes, but, in actuality, they’re not. Maybe seeing yourself reflected in a mirror makes you think about who you are in that space, instead of a neutral party.

TS: It does implicate the viewer. I’ve had this material for a while and I haven’t used it because it hasn’t quite made sense, but here it does make sense for the viewer to become implicated. I’m very happy to see how it transforms the space and how it transforms the viewer’s experience within the space.

AC: In making this body of work, have you had any insights about the political potential of parties?

TS: I think there is a great amount of political potential in parties. That’s always been happening historically in New York. There are parties that have become movements. Parties have become collectives or like churches, where people can go and have an experience.

AC: Also, safe spaces—

TS: Safe spaces or even spaces of revelation. In general, parties have extreme political potential and that depends on the scale, who does and who does not have access to them, where they are. Even a family gathering or a house party, those parties may or may not have the same level of political potentiality but are just as powerful in terms of emotional or psychological states.