A Partial Guide to Camp: On The Eyes Of The Beholder

Laurence Ross reflects on the Camp pleasures of New Orleans and the act of looking. His essay is accompanied by a selection of photographs by Colin Roberson that offer an intimate glimpse into the city’s queer nightlife.

Colin Roberson, Dillon and Shadow Self-Portrait, Burgundy and Gov. Nicholls, 6 pm, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

It’s more sublime and more camp to keep quiet about joy and then rescue the story later, once everyone else has abandoned it.

Wayne Koestenbaum, The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality, and the Mystery of Desire

There is a gay strip club in the French Quarter of New Orleans that my closest friends and I affectionately refer to as the Ballet. The Ballet is not the name of the bar, of course, but this mask of language rings just as true and allows a duality facilitating both a joke and sincerity when surrounded by the ears of an unknown public. Some joys are better kept quiet, secret, as to illuminate a stage too brightly is to ensure that no one can see a damn thing.

Standing outside of the Ballet, which is allegedly a favorite of John Waters, it is possible to peer inside in those moments when the door is open, when someone is in the process of coming or going. If there is anything about the experience of the Ballet that is like a peep show, it is that moment: the one before you enter. For once inside, you are most certainly no longer peeping, but taking in, being taken in. Once inside, what there is to see is very much up close and (at times unexpectedly) personal, cramped, in your face/space. (Depending on the type of spectator you are, you may be taken aback upon being taken in and gravitate toward a wall, though by no means will that location exempt you from participation.)

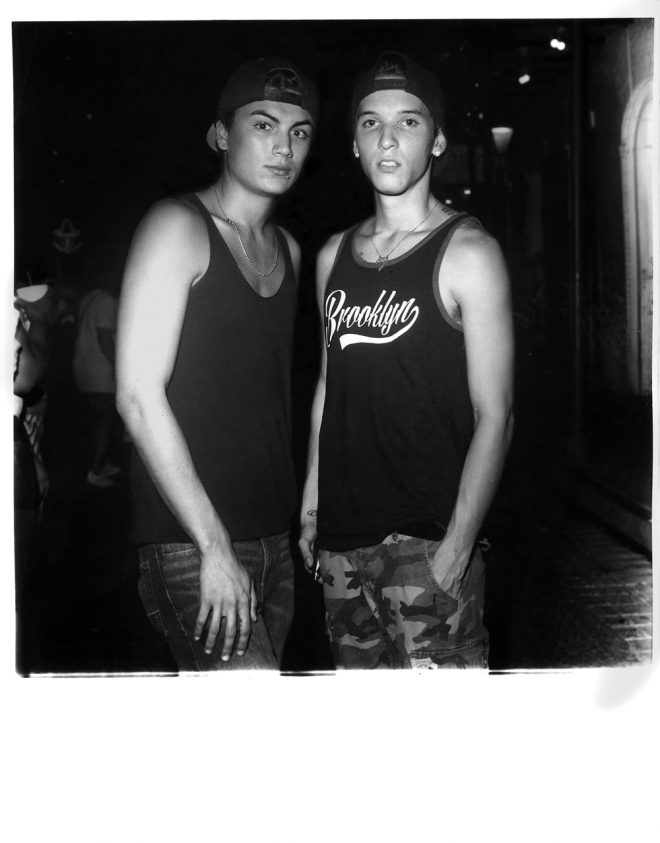

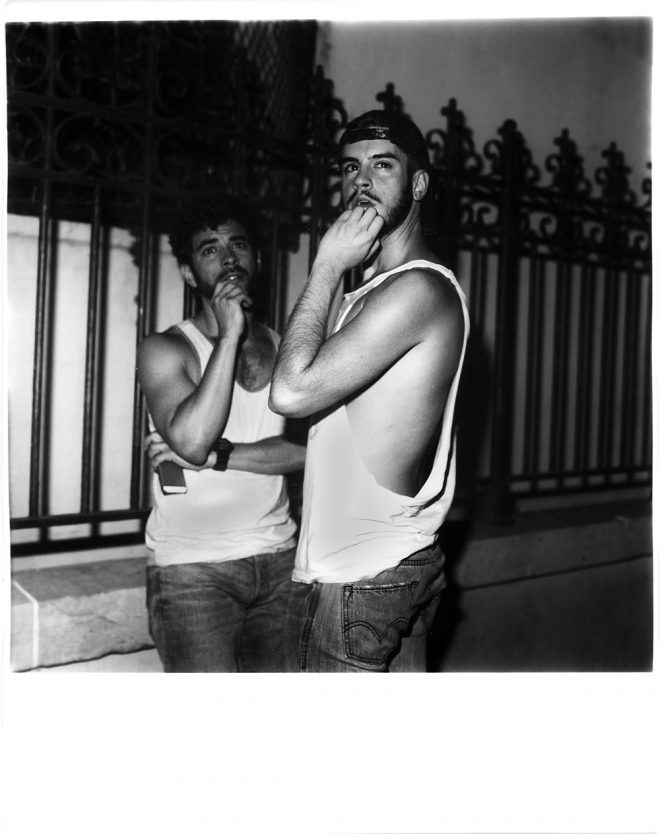

Colin Roberson, Newly Engaged, Bourbon and St. Ann, 1 am, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

However, from the outside, it is possible to maintain a level of remove that no one inside can seemingly manage or afford. Outside, you spy a backwards baseball cap atop a pimpled countenance, a collar and tie above a shirtless chest, an illegible tattoo arched across a stomach, a biker-gloved hand moving toward a nipple, or a sliver of pubic hair sliding into view, and then, before you know it, that door is snapped shut. Outside, one is kept on the brink of knowledge—the forbidden fruit has yet to be taken from the tree, has yet to be tasted. And, for me, this moment outside of the Ballet really is a matter of taste. Over the bustle of the crowd, I can clearly make out the vocals of Britney Spears singing “Ooh La La” (a single off of the soundtrack for The Smurfs 2). On its own, the song likely does little to stimulate, but combined with the sight of a cotton-covered rear bouncing from side to side, this mise-en-scène is enough to get a rise out of me. My excitement here is no longer within my control, the sensation of the Camp moment overtakes all else, and I smile.

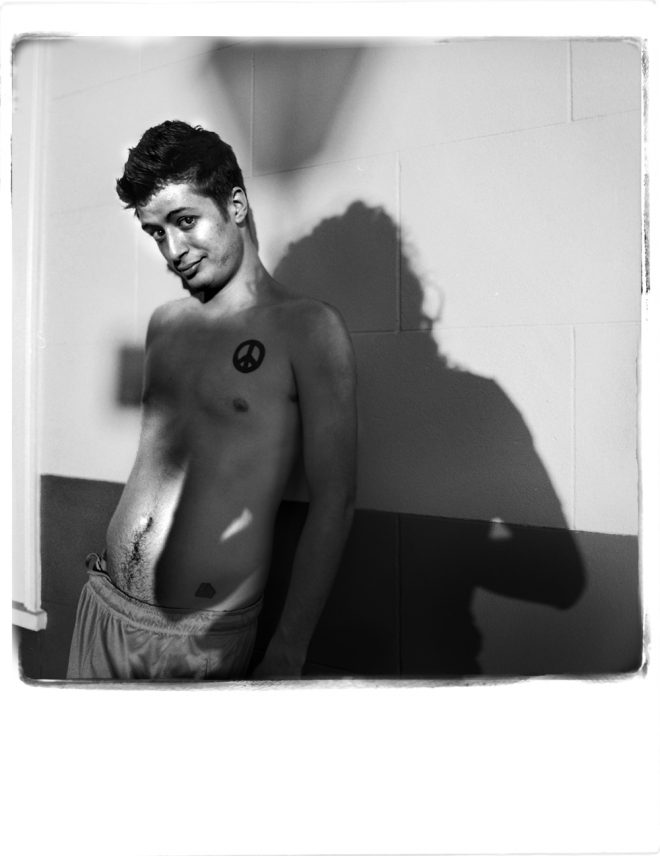

Colin Roberson, Dan, St. Claude and Marigny, 1 am, 2011. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

One of the finer aspects of living in New Orleans is the city’s propensity to turn any given moment into a public spectacle, into a spontaneous art piece/art space that is open to—and welcomes, even—participation. If asked to pinpoint the cause of this propensity, this penchant for creating a transcendent moment, it is difficult to know where to cast a finger, where to point. My instinct is to gesture toward alcohol or the old standby of Catholicism, though those are more so my own particular origin myths. And yet, at second glance, perhaps these suspects are not far off the mark. Perhaps, as water seeks its own level, I have sought out a city that resides on my preferred aesthetic plane.

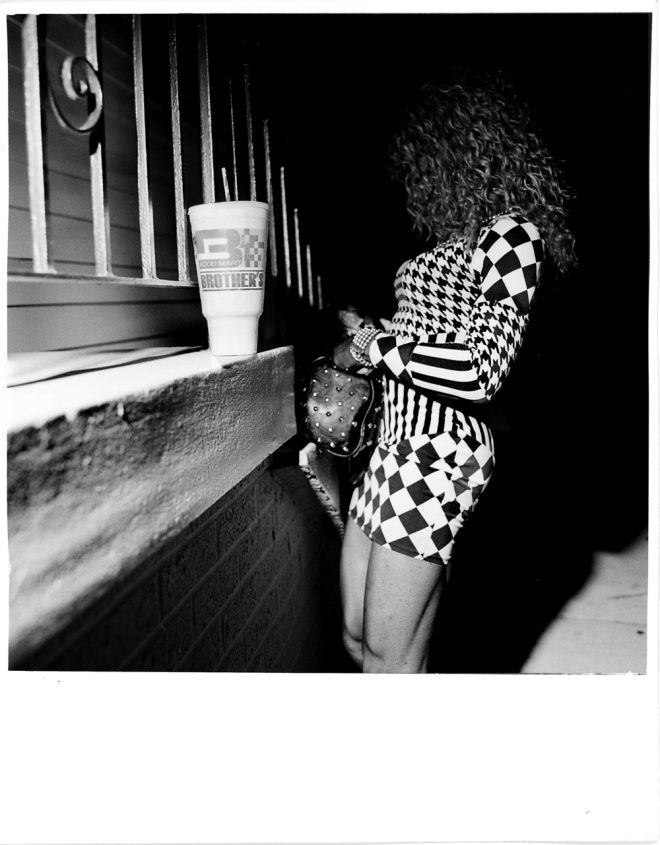

Colin Roberson, Danielle Rifling in Purse with 32 oz., Burgundy near Iberville, Half Past 4 am, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

Culture writer J. Bryan Lowder authored a series of articles for Slate, entitled Postcards From Camp, that speaks of Camp as a geographic physicality: “As a place, it is, of course, metaphysical, but also wonderfully, nauseatingly visceral. In short, camp is a country...Many people pass through, some establish vacation homes, and a select few—like myself—become townies.” If I am beginning to suggest that I originally moved to New Orleans because it is a country of Camp, that is not—entirely—true. But it is not entirely untrue either. There are the palm trees, which, during particularly turbulent weather, remind me of Mercutio’s death scene in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet, Leonardo DiCaprio weeping over the body in the midst of a set stage. There are the lattice corbels, in states of beautiful decay, that both have no purpose (no practical function of support) and have purpose (a decorative, if deteriorating, façade). There are the costumes—and not the China-manufactured masks for sale in the stalls of the French Market, but the handmade, full-scale imaginings of personae manifested through recycled and repurposed materials. And once, at Southern Decadence, there was the boy carrying his clothes in a plastic bag, suspended from a raised hand and an extended index finger, wearing nothing but a thong as SisQó’s dated summer song about that very same undergarment blared above.

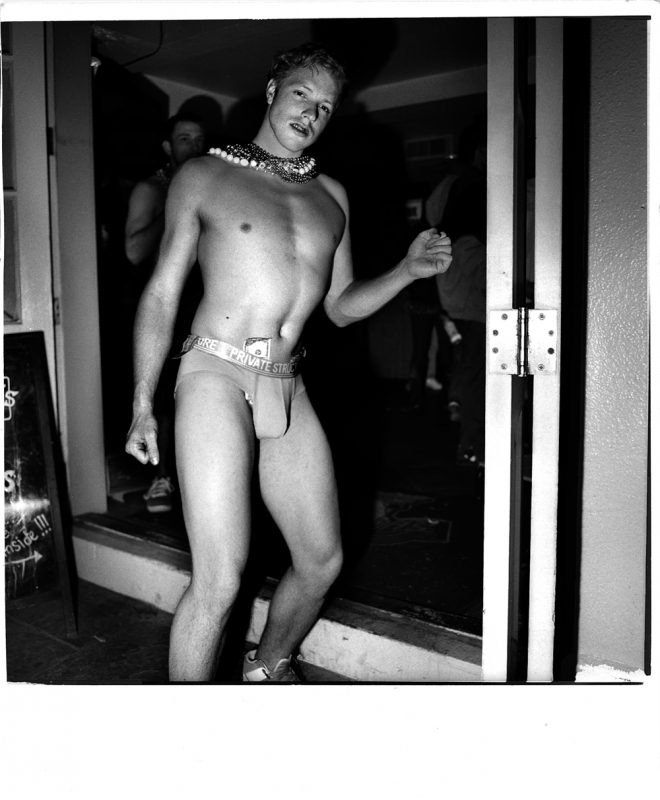

Colin Roberson, Midwesterner on Bourbon Street near St. Ann, Half Past Midnight, 2015. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

Inside the Ballet, the stairway does not lead to heaven but to the top of the bar. Male dancers clad in their underwear and sneakers step/skip/hop atop the counter, making their way around the four corners to entertain. One time when I was inside the Ballet, speaking with a drag queen who doubled as the DJ, I used the word entertainer in reference to one of the dancers, which caused her to issue forth a cackle that seemed unnecessarily cruel. After all, it was amateur night—who can tell? Perhaps that hip swivel with the novice’s jerk was meant to be just that—naïveté played up for the sake of the show, the illusion of a lack of form. Who was she to judge? (For that matter, who am I?)

Colin Roberson, Couple Arguing Beside Cathedral, Pirates Alley, 2 am, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

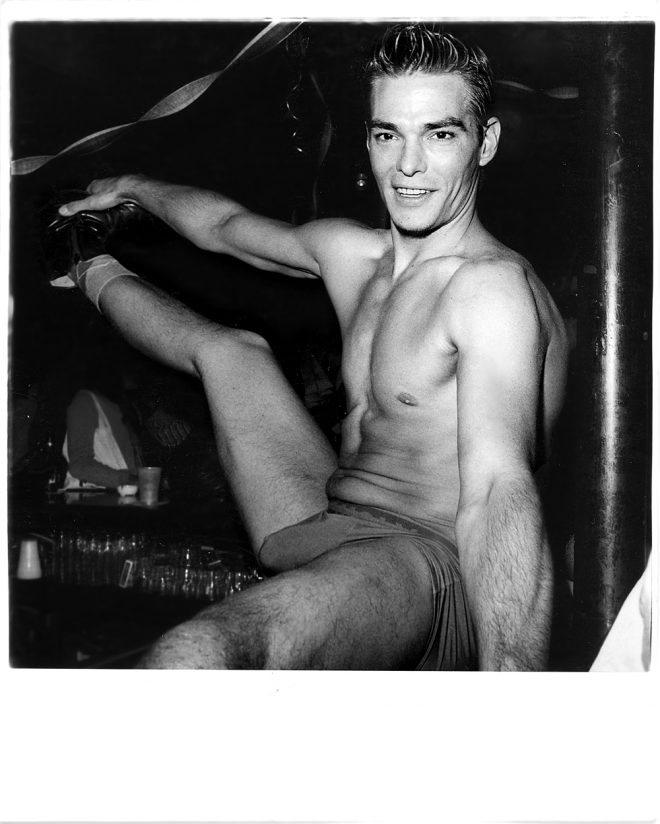

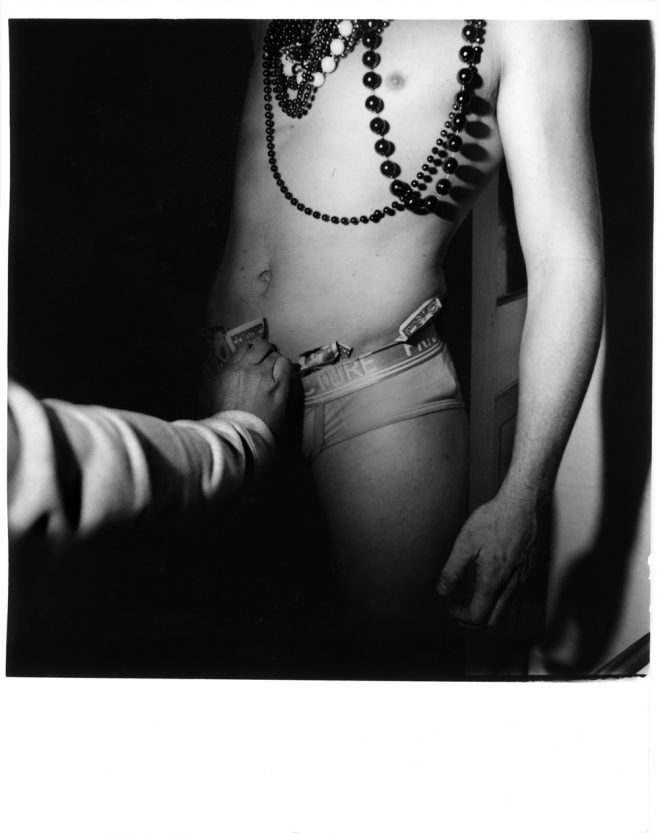

Though to judge is precisely what one must do if one is to separate the Camp from the quotidian. Camp allows one to separate the tragicomic from the merely tragic. The Camp lens is not an unbiased one—it entails a critical awareness of juxtaposition, of a happy incongruence. It requires scrupulous attention to detail, for the aesthetic (and I would argue, the art) revolves around nuance. I once saw a dancer at the Ballet with an ankle monitor tethered above the lip of his Nike, striking some balance between sensual seriousness and placating playfulness, performing a parlor trick involving his genitals and a Solo cup. In every sense, he seemed to be both free and confined, nearly naked yet practically bound. Then there is, of course, the underwear itself.

Colin Roberson, Appreciation, Bourbon and St. Ann, Half Past Midnight, 2015. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

In his essay, “Men’s Underwear,” Wayne Koestenbaum writes: “Critical objectivity about a stranger’s underwear comes easily,” and I’ll press upon two words here: critical and objectivity. The critical impulse when one is confronted with a stranger’s underwear is a necessary component to the judgment Camp requires. There is an assessment that takes place when faced with a pair of Hanes boxer briefs, Hugo Boss trunks, Calvin Klein briefs, an Andrew Christian jockstrap. But the objectivity in Koestenbaum’s statement requires a bit more reconciliation if we are to remain in the aesthetic realm of Camp. If the Camp lens is a biased lens, objectivity seems damning, the art’s undoing. I would argue, however, that the objectivity spurred on by the underwear of a stranger, in the context of a public spectacle/performance, causes a disconnect between the garment and the body that wears the garment. In that moment, the underwear separates, embodies itself as its own object, and exists in juxtaposition to a body that the underwear is only ever meant to partially cover. It is functionally costume, though functionless as underwear, being that the garment is not actually worn under anything at all. The boys become literally branded, and we are able (perhaps even asked) to read/interpret the scene.

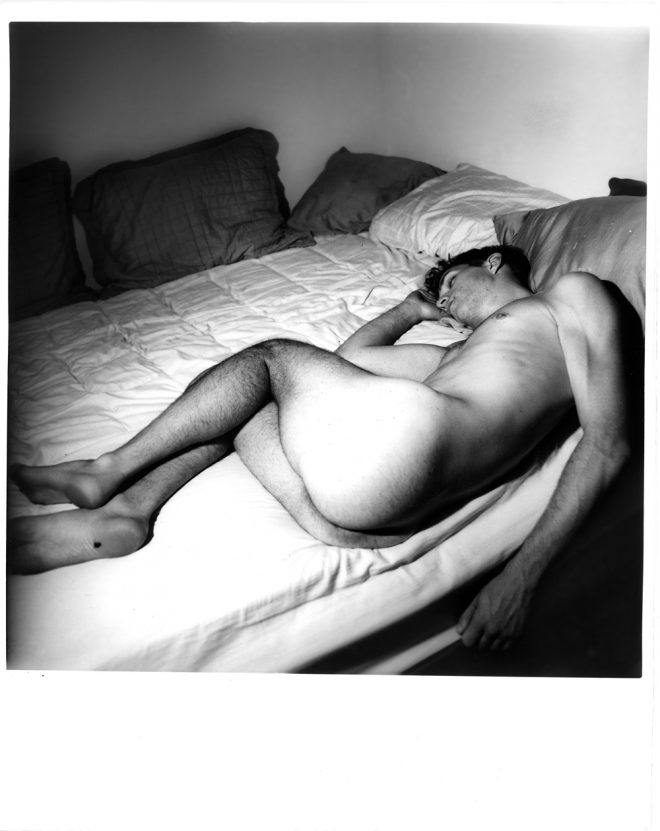

Colin Roberson, Jonas in My Bed, Burgundy between Reynes and Forstall, 5 am, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

“A boy wearing Carter’s underwear is a cipher,” says Koestenbaum. “He has no body.” And yes, this is Koestenbaum’s particular perspective, but if Camp as an art form originates with the critic, then this subjectivity is an elemental component of the work. For Koestenbaum, the underwear is part of an alternative language/understanding that expands the image of “boy in Carter’s” beyond its literal interpretation. The image transcends the factual reading our culture at large would yield.

Though a casual reading of Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” might lead one to believe the Camp aesthetic is built out of meticulously curated objects, Lowder cautions that “camp is not itself the nuance; rather, it is the pleasure that seizing upon the nuance evokes…camp—the pleasure of the nuance—is always fresh, forever sparkling in the eye of the beholder.” And if Camp does issue forth from the eye of the beholder, from the spectator rather than the spectacle, then it is an aesthetic—and therefore an incarnation of an art form—that is created by the critic rather than the artist. (Whether that art is “good” or “bad” is another conversation altogether—and one I find much less interesting.)

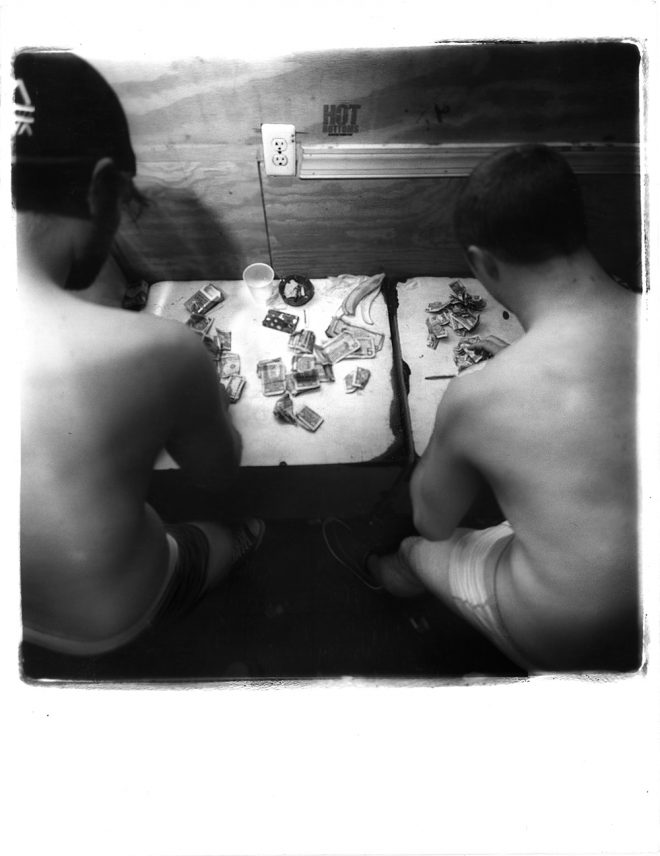

Colin Roberson, Counters with Banana Peel, Bar Locker Room, Half Past 4 am, 2015. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

If we accept the premise that Camp is created by the critic, we are left with the question of intention. Do I go out searching for Camp, or instead, do I happily stumble upon it? Perhaps the Camp lens, just as some believe about happiness, is only attainable if one is not trying. Perhaps Camp, as an aesthetic, is, if not exactly an accidental one, one that is a byproduct of other sensibilities. Several years ago, I busied myself devouring every Camp work I could find, and, no doubt, began cherishing the Camp aesthetic in my own life, collecting and cataloguing their instances. However, it was quite some time before I was able to identify aesthetically, to name, what exactly I was drawn toward. I could list only a spattering of qualities that excited my artistic sensibilities: a (nearly) absurd attention to physical details/objects, overblown physical gestures, lines of emotionless dialogue that were rendered all the more piercing for their flatness, a great deal of alcohol, an infatuation with artifice, queer sexualities, and a pervasive yet revelatory indulgence in ornateness. In short, these qualities, when combined, sent me into an altered state of aesthetic ecstasy.

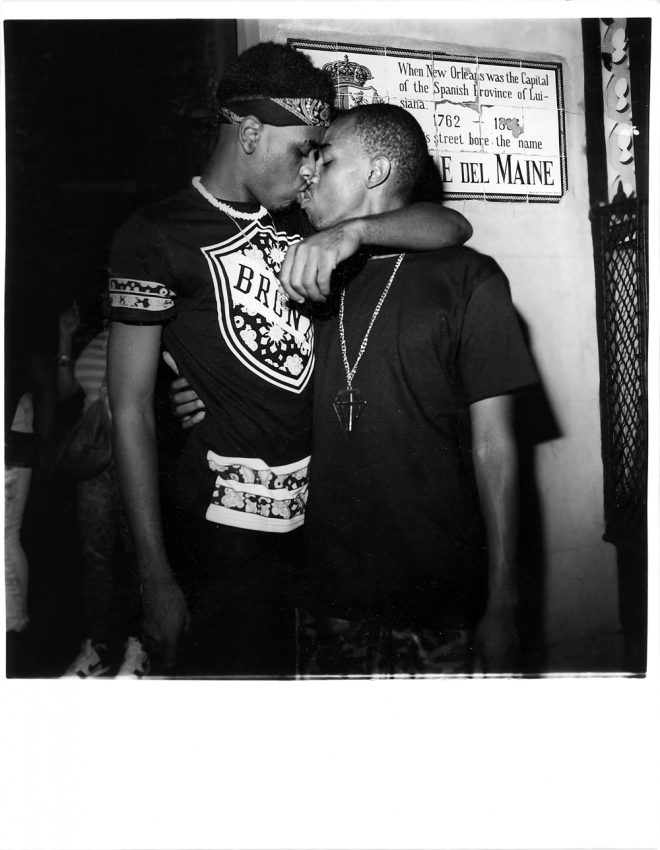

Colin Roberson, When New Orleans was the Capital of the Spanish Province of Louisiana, Bourbon and Dumaine, 3 am, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

Lowder names this state an “aesthetic erection”—“the delight arrives with the ego in tow to impose a little order. It’s in this stage that you realize you’re having a camp moment...and begin to consciously process whatever shimmer has instinctively tweaked you out.” Camp, again, is presented as an altered state, a type of drug, a catalyst for a shift in vision, an experience that can be, simultaneously, uniquely yours and also shared—just like the stage of a crowded theater. The critic may be origin of the Camp moment, but the critic is also who will ultimately dismantle it. (For what goes up must, eventually, come down.) It is during the comedown that the critic can return to a state of (relative) objectivity, to contextualize what he has seen, to mull over what exactly was meant—or not meant—by Eddy Monsoon and Patsy Stone riding in the Decadence parade immediately followed by Statler and Waldorf, the two miserly Muppet-critics who were forever removed from the heart of the show, perched on their balcony in semi-seclusion.

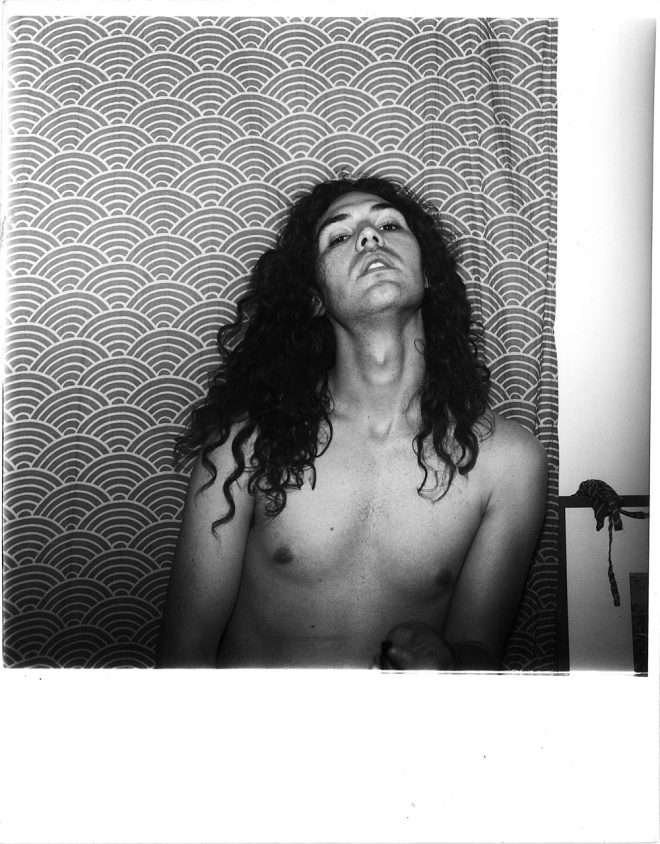

Colin Roberson, Self-Portrait After Dancing, Burgundy between Reynes and Forstall, 4 am, 2014. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

In that parade, it was the juxtaposition of Eddy and Patsy against Statler and Waldorf that sparked a piercing moment, that caused the arousal of artistic tension. I felt the pangs of Camp: Which pair are the real critics? Which pair the misers? Which pair perpetually laughing, fully comfortable in their own artifice?

Though, looking back, was that moment an instance of Camp? Or had the heat and the sugar rush from an ill-advised daiquiri simply caused me to pause, to linger and look at that scene askance? I’d like to say that I know Camp when I see it—an antique philosophical lean-to, I know. Of course, Calvin Klein’s recent lines of underwear, which have been historically cut from cotton, have now been cut from polyester. So these days, at a distance, who can tell?

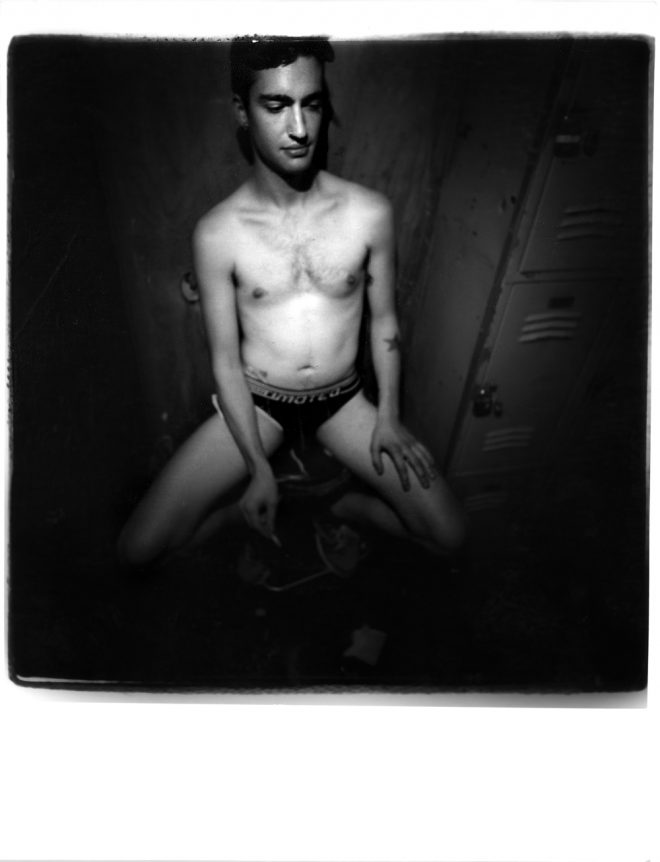

Colin Roberson, Zack, Bar Locker Room, 1 am, 2015. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

More photographs by Colin Roberson can be viewed on his website.