Occam’s Razor: Tennessee Williams at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Laurence Ross explores Tennessee Williams' affinity for hairless men in his paintings currently on display at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

Tennessee Williams, Le Solitaire, 1976. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

An intercourse not well designed

For beings of a golden kind

Whose native green must arch above

The earth's obscene, corrupting love.

—from Nonno’s poem in Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana (1961)

I can see from the doorway a painting that depicts the back of a man on a gray street on a gray night, Le Solitaire scrawled beneath his feet. Or, rather, these are gestures of a man along with a lone palm tree, a bare horizon, and a singular moon. The man more closely resembles a chalk outline against cold pavement than a fully formed figure capable of action. He stands between two bricks of red buildings—a sense of encasement, belittlement, claustrophobia. Only the green wisps of paint that make up the hazy mirage of the palm tree offer an oasis, a focal point for his eye and ours. But even this destination of hope seems dim as the fronds of the palm tree are thin, balding, and wilted with the burden of loneliness and loss.

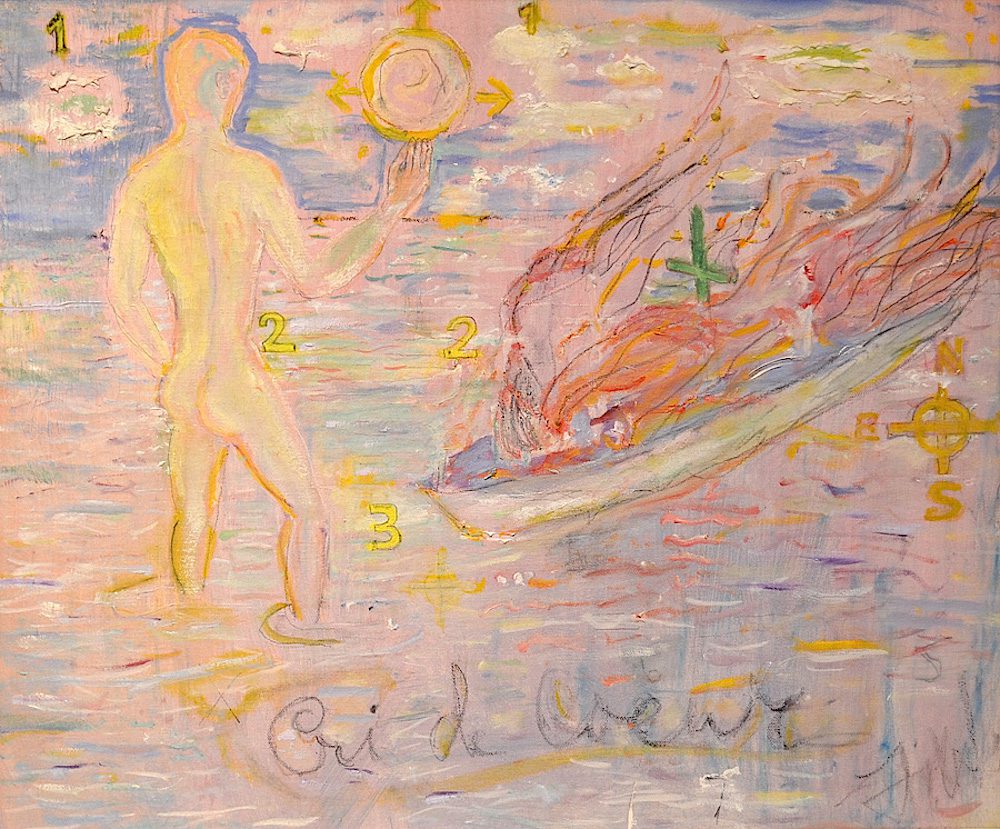

The stripped (if not crude) nature of Le Solitaire, 1976, is a recurring stylistic trope throughout the 19 paintings on view at “Tennessee Williams: The Playwright and the Painter.” In the more sensual paintings, pastels abound. Muted yellows, blues, pinks, and greens dominate bleary and fantastical landscapes. (Perhaps this is how the twilight mornings and evenings of Key West appeared to Williams, where he painted the vast majority of his works after the vigor of his career as a playwright had begun to fade.) Nude figures populate the canvases as frequently as if we’ve returned to the Italian Renaissance. And though these figures do not necessarily model the Grecian ideals of a muscular or full-figured bodily beauty, Williams’ nudes do remain as unapologetically naked—and hairless—as those older gods.

She Sang Beyond the Genius of the Sea, 1975, depicts an updated story of creation: a woman/creator with radiant rays in place of locks, holding a twinned trident over her head, bestowed with twice the power of Neptune. To her left, the bare back of one male figure; to her right, the hairless front of another. The painting is inspired by a Wallace Stevens’ poem, titled The Idea of Order at Key West, which reveals:

She measured to the hour its solitude.

She was the single artificer of the world

In which she sang…

And the two men she has sung into creation are indeed rendered not as her duplicates but certainly in her likeness; there is not a hair upon their bodies, their smooth and nearly translucent skins standing (or posing) ankle-deep in the placated waves. (Nothing betrays artifice quite like a hairless body in moments of intimate love/making.) If Key West is Williams’ version of an Eden, it is an Eden in which Adam has been gifted another man. And if this painting is Williams’ vision of desire—if not unearthly paradise—then this rapture is one that is unencumbered by natural body hair.

The absence of body hair is the embodiment of the unnatural or supernatural being. Body hair seems inextricably human, and in some ways, a line of defense against the more harsh realities of the world: reducing undue friction, warding off skin irritations, even filtering the air we breathe. The Roman gods, carved from Carrara marble, wear their skin smooth, ethereal, immune to such minor plights. (Meanwhile, on earth, Gillette markets the luxury of “flawless” skin, attainable with a razor named after Venus…) And if, as the exhibition at the Ogden suggests, Williams painted a number of these portraits as a type of love letter or diary entry about his romantic trysts, perhaps he allowed himself the generous liberty afforded to painters and the fantasies of children alike—to record with an appetite for invention, to edit according to the guidelines of romance, to willfully create mis-remembrances.

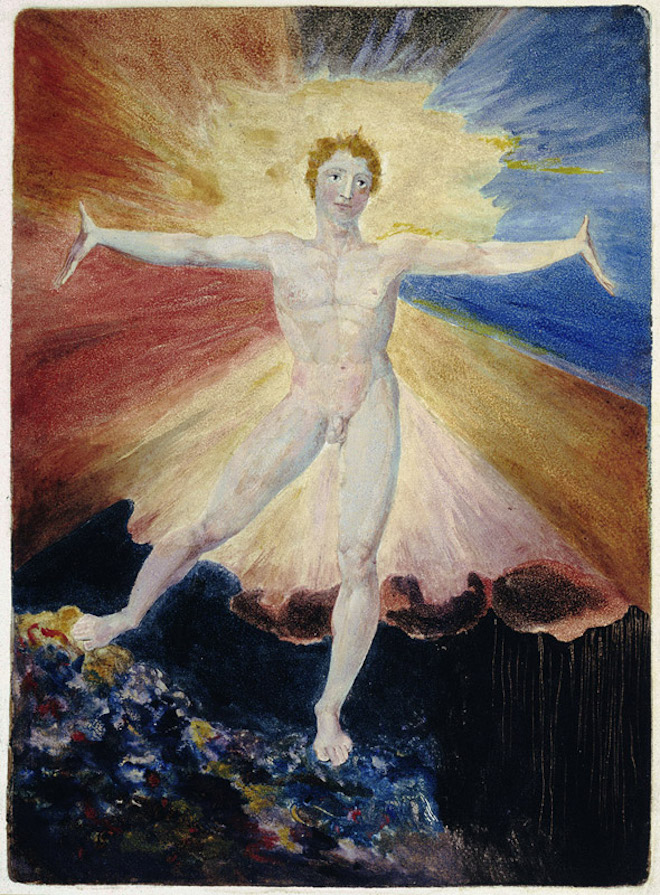

William Blake, Albion Rose from A Large Book of Designs, 1796. Courtesy blakearchive.org.

These touches of innocence coexisting with the patina of experience, part mysticism mixed with part reverence, echo the paintings of another famed author, William Blake. Take Blake’s Albion (also a son of the sea, Poseidon his father), standing nude, arms outstretched, amidst a sunburst of color, head in the clouds, defiantly (and frighteningly?) hairless. The smooth-skinned body seems to perpetuate as one of our most gnostic tropes, as our head also remains in the clouds, a veil against our more coarse realities. Even in Blake’s illumination for his poem, A Poison Tree, the naked enemy of the narrator lies prostrate on the ground but is still rendered with a mythological hairlessness amidst the aftermath of an utterly mortal feud.

In the morning, glad, I see

My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

Though perhaps this body should make us double back again to the paintings of Tennessee Williams and reconsider the phenomenon of a hairless body. The young man in Williams’ painting Lament for the Moths, 1978, (a sort of illustration for his poem of the same name) is rendered with delicacy, his left foot pointed as a dancer’s, his leg arched with poise. Amidst the blur of flora, he seems the most likely to be trampled:

A plague has stricken the moths, the moths are dying,

their bodies are flakes of bronze on the carpet lying.

Enemies of the delicate everywhere

have breathed a pestilent mist into the air.

And though the poem laments the velvety moths—a metaphor for fragile boyish men with which the painting bludgeons the viewer—the youth in the painting notably lacks even the slight body hairs the moth possesses, rendered all the more delicate as he lacks a pair of powdered wings to carry him to safety. If, in the past, the hairless naked body was a symbol of god-like power, this present suggests that a hairless god-like bronzed beauty may weaken one to an existence as fragile as ash, crushed beneath the heavy world, the feet of men.

Of course, the simplest explanation for why Williams did not paint body hair on his figures is that he didn’t possess the talent or the wherewithal. (Occam’s razor held to the throat of art criticism.) But this hair-thin line of reason seems, if not emasculating, to needlessly reduce the complexity of what it means to look at a work of art, and shaves away any possibility of wonder—an entirely human (and, at times, hairy) exercise.

Tennessee Williams, Cri de Coeur, 1976. Oil and pencil on Canvas. Courtesy the ogden Museum of southern art, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

"Tennessee Williams: The Playwright and the Painter" is on view through May 31, 2015 at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.