Not Black and White: An Interview with Ti-Rock Moore

Rosemary Reyes interviews emerging artist Ti-Rock Moore on her work and her place tackling racism.

Ti-Rock Moore at the unveiling of her Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series mural on July 1, 2015 in New Orleans. Photo by Marcus Carter.

Editor's Note

I came across Ti-Rock Moore’s work before moving to New Orleans, when I was first researching for my job at Pelican Bomb. I responded to the work because it addressed our nation’s crippling problem—racism—in an uncensored and unapologetic way. It felt accessible and real. At the time, there was little information online about the artist and who they were, but my best guess was that he was a young black man fresh out of art school.

After a chance encounter with the artist, I learned that Ti-Rock Moore was not in fact a black man, but a white woman. As a woman of color, I was confused about my own confusion—why I naturally felt such disappointment and betrayal. Don’t I want to live in a world where stereotype and race-based assumptions don’t limit what one can create and contribute? We’re obviously not there yet.

Needless to say my perception of the work changed, but more importantly it raised moral questions about the artist’s relationship with her work—work that is about identity. And in light of horrifying verdicts, massive protests, cold-blooded killings, and the urgent need to dissect racism in this country, I thought: What is the role of the white activist today?

The conversation to follow highlights Moore, the passions that drive her, and her rapidly expanding presence in New Orleans contemporary art.

—Rosemary Reyes

Rosemary Reyes: I’m interested in the moment when an artist decides to become an artist. Or more generally when a person chooses to pursue uncharted territory in life—flicking that switch. You have been making work for years, but only started presenting your work publicly one year ago. Was that somehow calculated? How did you know that you were ready?

Ti-Rock Moore: I’ve been practicing my whole life and I can tell you it was not calculated at all. Both of my parents were visual artists and I never had any intent to be one too. In fact, as a young person, I pushed back because of my parents, but it was always a natural thing for me. As I went on through life, and I am 55 now, I did what society expected me to do: I got respectable jobs, made a living, and went about my business. And, when I did retire, I never for one day thought I would become an exhibiting artist. I didn’t even think about it.

But in February 2014, I decided that I was going to put a few pieces together and have some friends come over to my house for cocktails to check them out. It was the first time that I had presented my work ever. I didn’t think about it going anywhere. I didn’t want it to go anywhere. I put some things together in a week, so they were really just concepts, but for some reason it gave me confidence. Then I read in one of the local publications that they were having calls for artists at the Ogden Museum and the Contemporary Arts Center and I thought, “Why the heck not?” There was nothing to lose.

I can remember I received a vague email back from the Ogden for their “Louisiana Contemporary” show that included a link to the list of artists that were chosen. I clicked on the link, went down the alphabet, and saw my name twice. I was alone in the room and tears just came to my eyes. It was an overwhelming and wonderful moment that said to me, “You’re producing real art, so go forward.” I have incredible respect for artists in New Orleans, the galleries and museums here, and never expected to be looked at as an artist that could fit into that world. The message in my art is what drives it. I’m realizing that message is resonating with people.

RR: How much is your work informed by current events?

TM: I’ve put work away because of things that happen in the news. For instance, I did a piece with young black men with their arms up and I put that away because, after Michael Brown, it felt too raw at that point. Now that a bit of time has passed, I've found myself reintroducing him into my work. I'm opening my first solo show at Gallery Guichard in Chicago on July 10 and am presenting an installation that uses a silicone replica of Brown's dead body displayed in front of a video of Eartha Kitt singing “Angelitos Negros” on the wall. I was concerned about the family's reaction to the work at first, but I knew I needed to ask their permission out of respect for their son. Not only did they give me their blessing, but they felt it would preserve the memory of their son and keep the movement going. They will be speaking at the opening.

RR: You make an interesting point about art, its relation to the present, and mindfulness. That makes me wonder what you think about the function of art in the past versus in the future.

TM: The majority of my art hopes to inform the future. Many new artists, and so much new art, have emerged out of the present-day civil rights movement. I recently participated in the “Manifest Justice” exhibition put on by Amnesty International in Los Angeles. I won the grand prize in that show, which allowed me to exhibit next to Shepard Fairey, Kehinde Wiley, and many others. All of the work in that show was born out of an understanding of the past and the current surge in activism. Activist-oriented art should project into the future, but past, present, future, they are all connected.

RR: When I first came to New Orleans last August, I saw your piece Just Sayin’ at the Ogden. You’re playing with language to highlight the word “vile” in the neon letters spelling “White Privilege.” Especially with this name, Ti-Rock Moore, and the content of that work, I assumed that you were a young black man. I have spoken to a lot of people who thought the same. Then I met you a month later, totally by chance, at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, and you’re a 50-something, queer, white woman, well at least according to my gaydar…

TM: Yes, it’s working.

RR: There are people who would question the validity of your work because you are coming from a privileged perspective. How do you address this skepticism and the fact that you are in a vulnerable position as a white person, presenting work about identity that is outside your lived experience?

TM: Prior to me ever coming out as an artist, that question haunted me. You know, “Where do I get off doing this?” I had to take a really close look at where my art was coming from. Again, because I don’t have a set plan for the pieces I create, they are a manifestation of my feelings. I knew my feelings were valid, but I have never experienced racism and likely never will. I have experienced white privilege 100 percent of the time and from my perspective that is the point: the unearned advantage that my whiteness holds and the rage that I have toward a system that supports that. The systemic racism that so deeply undermines blackness enrages me and that’s where my work comes from.

RR: How would you define that entry point? Advocacy? Empathy?

TM: I am an activist first and an artist second. My art manifests from my acute awareness of my own white privilege and the fact that this privilege is directly traced to slavery; the reality that white privilege is the cornerstone of American democracy. Many white Americans are in denial when it comes to their own privilege. Isn't this the great moral issue of our time?

RR: Some would say it’s just white guilt. I don’t think it is always productive to compare racism to homophobia, but do you think your sense of activism has anything to do with your experience living as a gay woman?

TM: Even in my 20s and 30s, trying to make it in our hetero, white, patriarchal system, white male entitlement enraged me. Though we didn’t use the same words to describe it, some of us were out there fighting the fight constantly. So, yes, I’ve felt hate; I’ve felt discriminated against, but the bottom line is, because I was white, I knew I could overcome it. At the end of the day, am I just a big, fat, bleeding-heart liberal with massive guilt? Perhaps, but my battle is to stop perpetuating mindless hate.

RR: You've recently started to sell pieces. How would you respond to the accusation that you are capitalizing on the very subject that you're defending? That is, you're using black bodies as a source of capital by profiting from your work.

TM: My art is expensive to make. I am very far in the hole, and it has gotten to the point that I must start making money to be able to make more art.

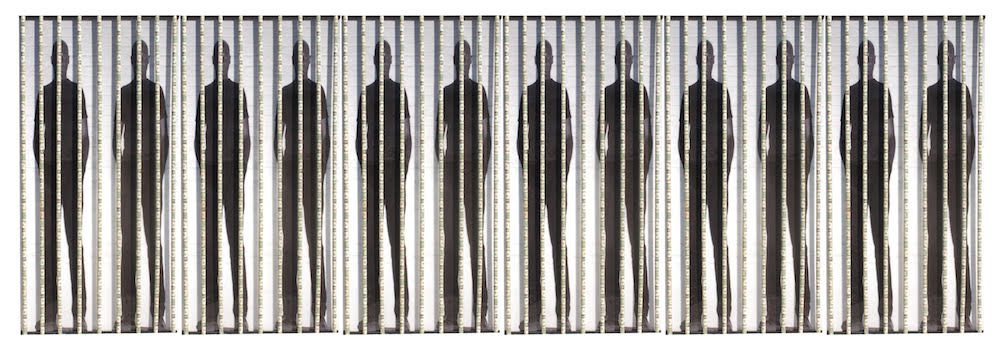

Ti-Rock Moore, Possession, 2014. Multi-media installation. Courtesy the artist.

RR: Let’s talk about your piece Possession, which won first place in the Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series contest at the Contemporary Arts Center back in October. These silhouettes of black men behind prison bars made of real dollar bills, it’s pretty literal. Because the message is clear, it’s accessible, which I really appreciate.

TM: I took a photograph of my friend, blew it up, and put it behind these money bars. Young black men are commodities in this country today and they have been since the days of slavery. Treating young black men as products is so deeply ingrained in the American system that I just had to put it out there like that.

RR: As you know, New Orleans has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, which disproportionately affects black men, but also black women. I’m from New York. Money masks a lot of the racism that occurs in New York, but here it slaps you in the face—the connection between racism, poverty, and a life behind bars.

TM: One in three black male children born in the United States will be incarcerated—one in three, not one in eight, not one in 15. Right after Katrina, watching images of people left behind, I realized how many people from my city were being treated like they were disposable. Even though I was able to evacuate, to get far away, I felt connected to them. That is what Possession is about—recognizing that connection and reflecting on a system that affects us all. We are perpetuating the problem if we don’t come out and discuss it.

RR: You recently unveiled a mural that was part of your participation in the Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series. You selected Brandan Odums as a collaborator to help you realize the project. Why did you want to work with him?

TM: In the first days I met Brandan during “Exhibit Be,” I showed him my artwork and he turned to me and said, “This is so dope.” He’s this brilliant young man that I think is so cool, so there is some mutual appreciation there. I’m not a mural expert and I knew I would be under scrutiny because I’m a new artist, so I wanted to work with only the best. I provided Brandan with the design and concept, then gave him full creative liberty in its execution. This mural is Brandan. We’re also both from New Orleans, both graduates of NOCCA, and we were both exhibitors in “Manifest Justice.” That was also really special for me.

RR: I want to return to the origin of the name: Ti-Rock Moore. It sounds like a rapper’s name, but it’s actually paying homage to another great local artist. Can you talk a bit about that?

TM: When I was a child, my father would talk to me about Noel Rockmore who was a friend of his. He always intrigued me because he was this genius artist. His work has stayed with me, but also the compassion my father demonstrated in talking about their relationship. In New Orleans, Ti is a popular name. It’s short for petite, so I smashed it all together and thought, “Wow, Ti-Rock Moore, that’s a great name.”

RR: How long have you identified as Ti-Rock?

TM: Just over a year now.

RR: So not long. Tell me about your other influences.

TM: My first big influence is my father. My father ended up raising me as a single parent and I grew up going to the city’s elite schools without much money—I was on scholarship. I understood my life was different than the other kids. I knew that they were being picked up from school and would have a big dinner with their families. I would get off the bus and wait for my father. When he would finally get home very late at night from his job, he would take me on a walk. He would hold my hand and say things like, “Look at the contrast of the telephone pole against the moon.” My father had a unique point of view and I saw through his eyes a lot.

One of my biggest present-day inspirations is Thornton Dial. There’s a book that was written about his traveling exhibition, which I saw at New Orleans Museum of Art in 2012, “Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial.” He was born in 1928 in Alabama and he’s been through hell in his life. He was a great motivator for me. Another big influence artistically is classical ballet. That was my first passion in life.

RR: I feel like dance is a very visceral art form. There’s no other art form that moves me in the way that dance moves me. There’s something about seeing people articulate ideas with their bodies that elicits a potent emotional reaction. It is a similar feeling that comes through in your work a lot, like someone punching you in the gut.

TM: It was the first year that NOCCA opened when I began dancing. I was 13 and most kids had already been studying for years. I knew what art was and my obsession with ballet came from that visceral place you mention. Every movement I made, even if it was just a plié, came from within. When I divorced myself from ballet, which I did because I became consumed by it, nothing could ever fill that hole, that loss. You have just helped me realize that my art now is coming from the same damn place. It’s coming from a place I can’t explain.

RR: Well you certainly have chutzpah. There’s no doubt about that.

TM: Thank you. I take that as a compliment, but once the time comes that someone does approach me and thinks I’m out of place—and I expect that will happen if I continue to have a larger audience—I’ll hear it and I’ll take it in. I’ll try to respond, but ultimately I’m just doing what comes naturally to me.

View of Ti-Rock Moore's collaborative mural with Brandan Odums as part of the Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series. Photo by Ti-Rock Moore.

Editor's Note

Ti-Rock Moore took second place during the final round of the Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series contest at Art Basel in Miami. As part of the prize, she unveiled a mural at 855 Baronne Street in New Orleans on July 1. Moore will also be included in three exhibitions in New Orleans all opening on August 1: “REVERB” at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street), “Louisiana Contemporary” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street), and “Levy” at Boyd Satellite Gallery (440 Julia Street).