Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow: On Baldness

Benjamin Morris delves into the many implications of baldness in American pop culture and society.

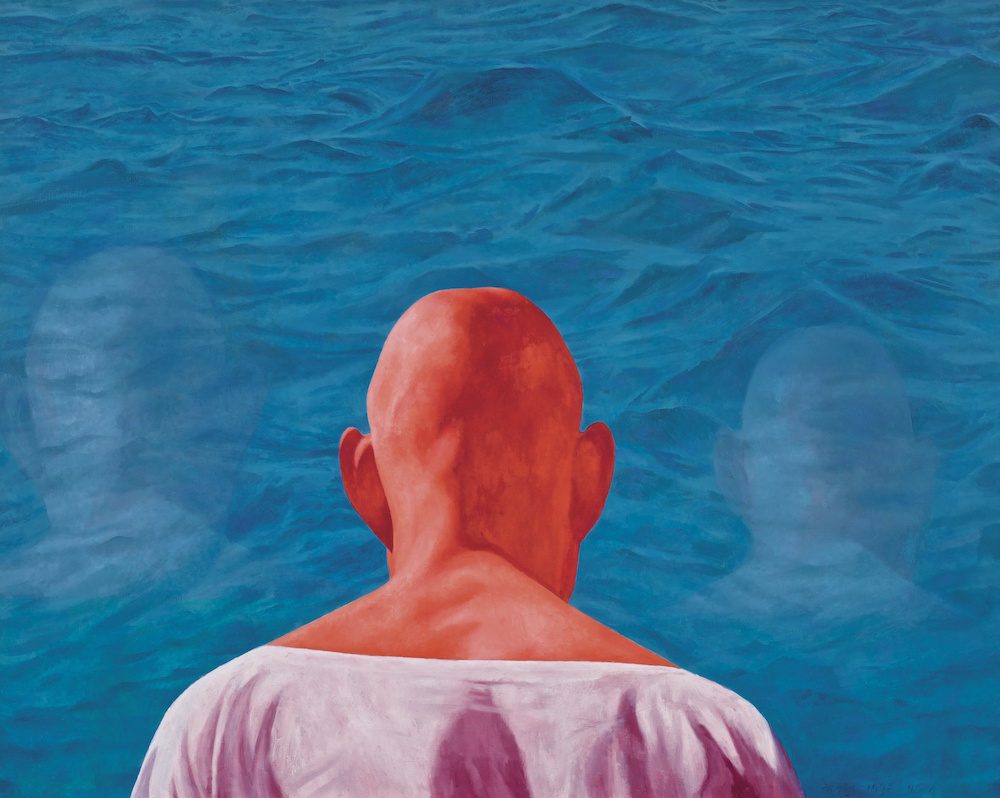

Fang Lijun, Gazing at the Sea, 1996. oil on canvas. Courtesy Sothebys.com.

No discussion on the topic of hair would be complete without consideration of its absence. To the extent that hair serves as an aesthetic choice, a symbol, a mark of identity, or political statement, the loss of hair often serves in exactly the same way. Granted, among most, its loss is unwelcome, and over the years has given rise to a range of treatments, from attrition (in the comb-over) to deception (in wigs or toupees) to medication, such as Rogaine, whose famous tagline has fueled countless parodies on late-night television.

To date, a range of works in a variety of media—film, visual art, literature, performance, and others—have explored the causes for and consequences of hair loss. Frequently baldness suggests conformity and the eradication of individualism, as in Stanley Kubrick’s iconic Vietnam-era flashback Full Metal Jacket (1987), whose ranks of recruits are sheared like sheep during basic training. Such forced hair loss often signifies totalitarianism; important to note is that this symbol isn’t reserved strictly for men. Indeed, in novelist Sarah Hall’s 2007 The Carhullan Army, its meaning is reversed: a rebel enclave of guerilla women fighting a dystopic future British state shave their heads in solidarity with one another. More recent depictions include Charlize Theron’s portrayal of Furiosa in this summer’s Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), whose ass-kicking rebellious buzz-cut has critics hailing her as a new feminist idol.

In ancient times, the shaved head played a powerful role in one of the most famous cryptological schemes of all time. In Caesar’s cipher, a letter-switching code was written in ink on the shaved head of a soldier who would first allow his hair to regrow, then pass through enemy lines undetected. If caught, he could convincingly claim not to carry any sensitive information, then upon reaching his allied commander he would shave his head to reveal the message beneath. Apart from overt militarism, however, baldness is also often associated with evil or degeneracy—as in Harry Potter’s Voldemort or Superman’s Lex Luthor, two of the many classic bald villains in popular culture. In such cases, the unencumbered proximity of their skulls to the outside world suggests a corresponding proximity to death (that which they cause, and in Voldemort’s case, his own). Their cue-ball clean heads, without even a wisp of hair, signal a type of unnaturalness, something human-but-not-quite that enhances feelings of revulsion and horror in readers and viewers.

To be sure, popular culture also enjoys its share of bald heroes, such as Bruce Willis’ Officer John McClane in the Die Hard series, or any protagonist played by Vin Diesel, Jason Statham, or the Rock (Dwayne Johnson). Moreover, that baldness is also a symbol of vigor was made abundantly clear a decade ago when the very bald French footballer Zinedine Zidane stunned the world by head-butting Italian player Marco Materazzi in the 2006 World Cup. Analyses of Zidane’s preternaturally robust skull—and its skilled application to Materazzi’s chest—immediately proliferated in ways that marveled at his talents, with one argument suggesting the act would not have been nearly as shocking, or visually compelling, had “Zizou” employed a set of luscious locks to do so. Here, baldness became immediately synonymous with machismo and strength, regardless of whether Zidane was indeed responding to the Italian player’s rumored racial slurs or affronts to Zidane’s own mother and sister.

Finally, in considering motherhood and sisterhood, an increasingly familiar female presence has emerged as an alternative vision of baldness in contemporary culture—the patient currently undergoing chemotherapy for cancer, whose baldness has become a symbol not just of her treatment but also her survival. Though past societies may have been swift to stigmatize hair loss (even the medically-induced variety), nowadays hair loss of this type serves both as an identifier and a badge of honor—indeed, a new form of beauty. Rather than a symbol of death, the bald head, wig or not, becomes instead a signifier of prolonged life.

In Baldness: A Social History, scholar Kerry Segrave argues that baldness has never meant simply one thing, that its meaning has changed considerably over time, dependent on context, medium, audience, and available visual iconographies of the day. Such an observation informs our gaze even in the present day, when the range of iconographies for hair and hairlessness alike seems ever to grow. For those interested in visual culture, however, it is worth considering as well a curious medical fact: that the surface of the cranium is home to more oil glands than on other areas of the body, oil glands that lubricate both the follicles (when present) and the skin. How curious that those oils, continually produced, lend the skin a shine that is almost, under certain conditions of light, reflective. If, then, a bald head partly resembles a mirror, what are we supposed to see?