Mapping New Orleans: The Broadsides of “Unfathomable City”

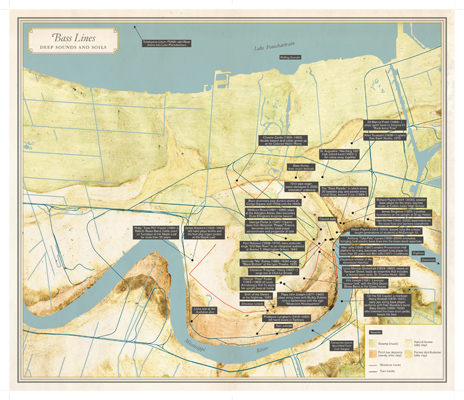

"Bass Lines: Deep Sounds and Soils" from the book Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. Map concept by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro and Rebecca Snedeker, cartography by Jakob Rosenzweig, artwork by Katie Holten, and design by Lia Tjandra.

When Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas (University of California Press) appeared this past autumn, outlets and reviewers across the country praised its efforts to capture the complexity of life in the Crescent City. Part of the appeal, as with its sister publication for San Francisco, focused on the atlas’ detailed visual component. Accompanying the essays by writers and scholars such as Richard Campanella, Antonia Juhasz, and Joel Dinerstein were hand-crafted maps of the city drawn by a team of expert cartographers and artists, maps as meticulously researched as any of the texts.

The editors of Unfathomable City, Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker, have maintained that the two components of the book function much like hydrogen and oxygen in water: together they make one element, but individually they have their own important properties, histories, and purposes. To further highlight these singularities, this spring Solnit and Snedeker reissued four of the maps as independently-published broadsides with condensed versions of their accompanying essays. Partnering with the New Orleans Museum of Art, A Studio in the Woods, and others for a series of public and semi-public events, the hope is that the dissemination of these broadsides, as arguments and expositions in their own right, will sponsor a wider conversation about issues in New Orleans’ artistic and cultural life, and the ways in which our culture informs our history, our politics, and our urban footprint.

In one sense, this new format introduces a metaphorical dimension to the work of the atlas, suggesting that the broadsides are roadmaps to a different means of viewing and understanding the city. Taking on the form of a guidebook’s fold-out map, they emphasize what scholars call “dark heritage,” or “heritage that hurts,” revealing the convoluted, often difficult pathways that mark the local terrain. The “Lead and Lies: Mouths Full of Poison” map makes this notion abundantly clear, rendering the levels of lead in our soil in stark, visible terms, particularly the saturation along the bend in the river that represents the Ninth Ward—the city’s poorest neighborhood, built on land which exhibits its greatest toxicity. From a bird’s eye view, the geography of New Orleans is such that roads are not needed to recognize individual neighborhoods; the import of these maps is that they illuminate surprises that should come as no surprise at all.

Not only do these free maps-as-objects allow for the wider dissemination of the information, sending these snapshots of New Orleans’ history and geography further in the world than the books alone could have done, they are ideally sized for taping to a refrigerator door or passing around like a samizdat tract. They also allow the details that the book format inadvertently disguises to emerge. For instance, on the map titled “Sugar Heaven and Sugar Hell: Pleasures and Brutalities of a Commodity” only an attentive eye would note the twin dots along Bayou St. John representing dialysis centers. Caught in the crease of the spine, they’re easy to overlook—but on the broadside they’re as plain as day, raising the question of why one neighborhood would have two centers so close to one another when other neighborhoods in clear need of such facilities (such as Gentilly, the Upper and Lower Ninth Wards, and all of Lakeview) would harbor none. Such a realization illuminates the inequities in the local healthcare system, and enables readers to advocate more fully for equality in public forums, exactly the kind of social and political awareness that the book as a whole was intended to raise.

As Solnit and Snedeker have repeatedly stressed, the work of Unfathomable City as a whole is not to provide a portrait or snapshot of the city at one time, but rather to encourage readers and viewers to more closely attend to the city in which we live, and begin to unearth patterns, principles, and traces of ideas and moments that reveal our impact on it—both immediate and long-term. In that sense, they straddle past, present, and future: for if these maps represent roadmaps or guidebooks to a shared, if contentious and complex past, then they also point to the possibility for further investigations in years to come. No doubt, as the city approaches the tricentennial of its founding in 2018, such reference materials will again require considerable revision.

Editor's Note

As the final event in the series, artist and filmmaker Cauleen Smith has created Depth Procession: Go Low, Go Light New Orleans, a musical and storytelling guided bus tour. Though the tour on June 7 is now full, you can be on the lookout for the former school bus making stops for storytelling and performance along a route derived from the map "Bass Lines: Deep Sounds and Soils."