On (Un)Masking

Yasumasa Morimura, Daughter of Art History, Princess B, 1990. Color photograph, transparent medium. Courtesy the artist and the New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Diego Cortez.

Even if I had not seen "Brilliant Disguise: Masks and Other Transformations," the title of the exhibit is enough for me to muse my way to lines unknown, but lines inevitably there for the reaching. That is the trouble/pleasure in talking about a physical object that is also a concept, a noun that is also a verb, a word that has a history and is therefore layered.

When I looked at the first masks in the exhibit, I thought: this is “happy,” this is “doubt,” this is “man.” The mask—a solid object—upon first glance translates into a solid expression, a physical object meant to represent an emotion/state-of-mind/state-of-being. The mask is an attempt to manifest into existence some expression that would not otherwise be manifested. I look at a mask constructed of papier-mâché, wax, paint—the layered materials manifesting a unified whole, a mask (re)presenting a face.

When I look at a mask and think this is happy, I have set up a simple mathematical equation for myself. This (mask) = “happy.” The trouble here is that math is much more complicated than our grade school teachers led us to believe. Math is not all concrete numbers. There are concepts (Forms) like variables, like infinity, like zero. A mask may equal “happy,” but those quotation marks around the word serve two purposes: one, to highlight the signified concept “happy”; the other to highlight that a quotation mark is an equals sign turned on its side, askew, highlighting that what we are seeing is a tilted perspective, a subjective perspective, the perspective of the artist/viewer/wearer/critic/reader (you choose). If x is defined as y, what is y? If the mask is defined as “doubt,” what is doubt? What have we figured out?

Much of what "Brilliant Disguise: Masks and Other Transformations" attempts to do is precisely that—to give us a y (a why), to weave and braid seemingly different expressions of masking across a wide swath of time and cultures into—if not a narrative exactly—a collage of tropes and intents, touchstones of purpose and utility. Miranda Lash, the curator, gives us context, the ability to see in a room full of objects (forms) a matrix of meanings (Forms).

There are many mediums showcased in the exhibit—wearable masks, photographs of masks, paintings of masks, even a film with masked actors. But one medium seems conspicuously absent: the written word. If one dons a mask to alter/enhance/disguise/adapt/perform/pronounce an identity, the action is germane to the work of the writer. Look at me; do not look at me; this is me. This is my face, my voice, or at least the one I choose to show you now.

Roland Barthes suggests that the author of a text is continuously engaged in a type of masking, and therefore a type of sheathing/erasure/death. William Blake’s life mask/death mask—a replica of the original by Patti Smith, herself an author/artist—is simultaneously a sheathing of the author’s face, an erasure of his facial features, and a distinct absence of (his) life. The author’s “voice,” however authentic it may or may not sound, is inherently an artifice. What you are looking at is not William Blake’s face but a replica of a replica of William Blake’s face—and William Blake the author similarly disappears beneath the layers of his writing. Barthes, in his essay “The Death of the Author,” refers to writing as “the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing.” When it comes to identities in a piece of prose, the author’s is always the first to go—the writing is not the author (or the author’s “authentic” self, whatever that may be) but a performed self, an identity that is constructed in much the same manner as any type of mask, regardless of medium.

Even if the author’s voice is distinct—as distinct as any individually crafted mask may be—it is still a type of screen, a type of disconnect from the person of the author. (And in fact, several of the masks in the show incorporate screens, the screens used as a base upon which to build and embellish.) Barthes notes that when “this disconnection occurs, the voice loses its origin, the author enters into his own death, writing begins.” The voice is the mask; the prose is the performance; the essay/this essay (just) a show, another showing of self.

Though wearing a mask is not an inherently disingenuous act. To say that the mask-wearer is two-faced would be reductive. To say that the mask-wearer is multi-face(te)d would be more accurate. Just as John Waters gives us a series of grotesque caricatures of his own head, his trademark mustache prominent on each red lip, masks and voices may amplify some aspect of the origin rather than completely disintegrate it. The mask may emphasize to us that John Waters the public figure is just that—a figure obscured by our viewing of him, a figure/artifice packaged for the public, which, as the series of images progresses, becomes increasingly blurrier.

It is not the case that one face is “true” or “real” and the other(s) false or fake; the audience simply sees whatever face is being presented in the present moment. And I, this “me,” the critic—like the mask—am an (inter)changeable appliqué, a façade that is always (under) construction. The next time you see me, I may be unrecognizable.

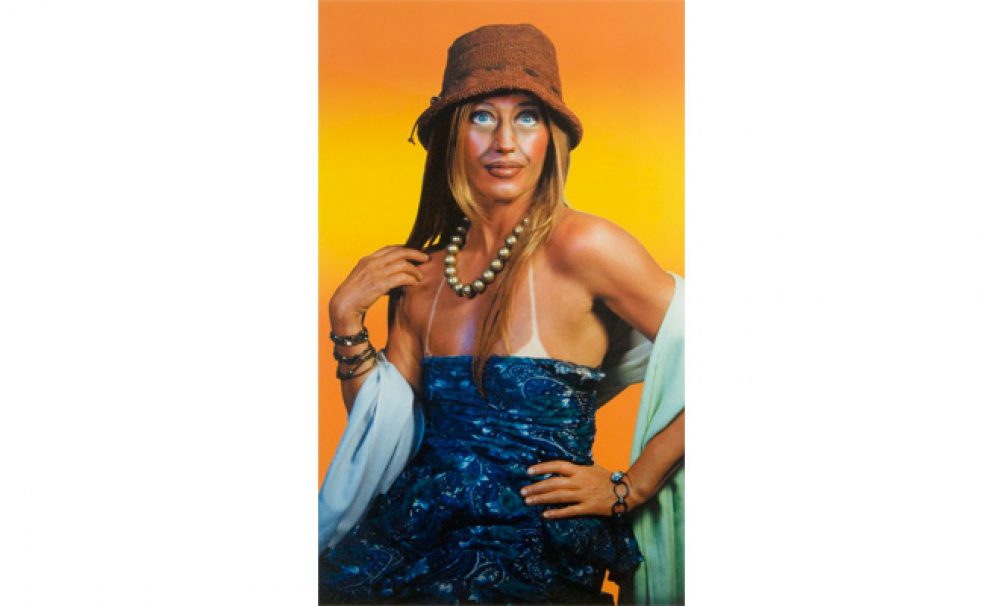

Cindy Sherman, Woman in Sun Dress, 2003. Lambda C-print. Courtesy the artist.

By wearing a mask, the wearer dons a new person/persona, the old person/persona rendered mute. What is prominent, what becomes present or performed, is the mask itself. When Cindy Sherman adopts a new image, she ceases to be Cindy Sherman and becomes “Cindy Sherman.” This photograph of an orange-hued woman with tan lines, with a bare shoulder to draw our attention and a blue paisley dress that is slipping down her breasts to expose the white triangled reminder of the season’s bikini top eventually gives way to her face, seemingly inflated with silicone, cheeks that appear immutable, eyes that stare from a face that looks like it could be cut from cardboard, eyes that appear to be trapped behind the front she has created. Cindy Sherman the photographer dies to become “Cindy Sherman” of the Hamptons. Cindy Sherman the artist shows us face after face that we have no continuous countenance.

This existence of the author as masked was made poignant when I was at the exhibit’s opening and I met a woman I had already met two months before. “I didn’t recognize you,” she said. And it was true—the last time we had met, I wore a completely different costume. The last time we met, we met at a fashion show. This time, an art gallery. At the fashion show, I was dressed to be seen; at the gallery, like so many other people who attended the opening that evening, I chose a conservative, (mostly) inconspicuous black ensemble. I chose, like so many others, to wear the costume of “museum goer,” dark colors, serious glasses, soft and slow steps. It almost seemed we dressed en masse to allow the art to take center stage.

Of course, there were other gallery goers that evening who were dressed not to play the part of the spectator but to be a part of the spectacle. Sequins. Neon. Some wore actual masks covering their faces. I think I remember a cape. Literal mask or not, we all stepped into and were all part of the masque, the processional, performing body moving with near-choreographed movements from piece of art to piece of art, the simple act of entering a public art gallery the catalyst for that transformation.

In a manner of speaking, by donning a mask, the wearer—however temporarily—is snuffed out. At least the wearer as he is commonly, daily perceived. The person is subdued, reduced to a backdrop, a shadowed/sheathed presence—Nick Cave’s Soundsuits stand in the middle of the exhibit as full body sheaths, suggesting that a mask transforms the entire person and is not (never) simply a covering for the face.

Barthes even emphasizes what many of the exhibit’s ritualistic masks imply: that “in ethnographic societies the responsibility for a narrative is never assumed by a person but by a mediator, shaman or relator whose ‘performance’—the mastery of the narrative code—may possibly be admired but never his ‘genius.’” If the notion of authorship values, as Barthes posits, the “human person,” then it seems natural that the mask be inherently non-human. Whether looking at the "animal cap crest mask" from Nigeria or Cao Fei’s photographs of children dressed as anime characters, neither of these incarnations of identity are human—they are animal, they are superhuman, they are other. And in the same way that these children may still appear childish, authors and artists may also appear to be their “natural” selves in their “natural” habitats—the trouble being that to the casual eye, the author/artist is not wearing a costume. An artifice may be so good that it may pass for human, just as Superman can, at times pretend to be Clark Kent.

Barthes reinforces the importance of the mask over the wearer when he states: “Linguistically, the author is never more than the instance of writing, just as I is nothing other than the instance saying I: language knows a ‘subject,’ not a ‘person,’ and this subject, empty outside of the very enunciation which defines it, suffices to make language ‘hold together,’ suffices, that is to say, to exhaust it.” Any given moment of authorship is a moment of mask-wearing, a moment in which the author as a person ceases to exist and replaced by the author’s voice—that particular instance of the performed I. This is prose/work/art in which, as Barthes says, the author is “diminishing like a figurine at the far end of the literary stage.” Barthes, himself an author, keenly aware of the implicitly performative nature of language, that the blank page is the stage, and even the first-person pronoun not the author but an actor.

Barthes also reinforces that a mask is an inherently “present” medium, which is why Lash is able to curate such a large swath of pieces that seem to seamlessly span time and culture. The exhibit, much like one of its many featured masks, is, as Barthes says of a text, “a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash.” In other words, the exhibit is a collage in the same way many of its literal masks collage materials: feathers, wire screen, papier-mâché, paint. The I s of the author are much like the eyes of the performer—indicating a person is there beneath the surface, but also indicating that what we are looking at is surface—a performed identity overlaying the person masked beneath.

Much like Max Luthi says of the fairy tale, when the artist/author/authority is distanced and deemphasized, there is no one interpretation, no single definite/definition. “In the multiplicity of writing, everything is to be disentangled, nothing deciphered,” says Barthes. And this seems the most useful function of criticism: to disentangle, to show a way (not the way) to connect points into lines, into a webbed matrix of understanding. Of course, just because there are an infinite number of ways to construct a web does not diminish the fact that certain webs are stronger than others. Some webs are constructed to carry more weight, and still others constructed with the capacity for beauty. Perhaps the best of webs (as the best of criticism) are constructed for both. Bathes denies an ultimate meaning to texts (and to the world), granting a freedom that surely makes some uncomfortable, others angry. But viewed another way, who wouldn’t want to be able to ceaselessly mask themselves? In place of a static self, we gain the ability to invent and reinvent our identities as often as we please, without the burden of maintaining some notion of an “authentic” face. This fluidity draws on the past as much as it promises the future.

“To give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing,” writes Barthes. And since the critic is also an author, this limiting, this closing, would apply to criticism as well. An essay (or an art exhibit), at its essence, never really ends. It has an end, yes, but an end that is more of a resting place. There are points of pause, and even points of exhaustion, the points of not-knowing that are the essayist’s greatest muse. Samuel Beckett’s narrator in The Unnamable captures the essayist’s internal dialogue with his closing lines: “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.” There is an implied continuation, and while not always happy, certainly always an ever after.

The final piece I encountered in Lash’s curation was a full-length mirror, rimmed with gold. The final piece was, in no way, a final piece. After confronting/contemplating so many masks, you are left to confront your own. There is your souvenir; no need to visit a gift shop. That is the mask you will carry with you out the door. You may take a moment to fix/affix yourself as you please.

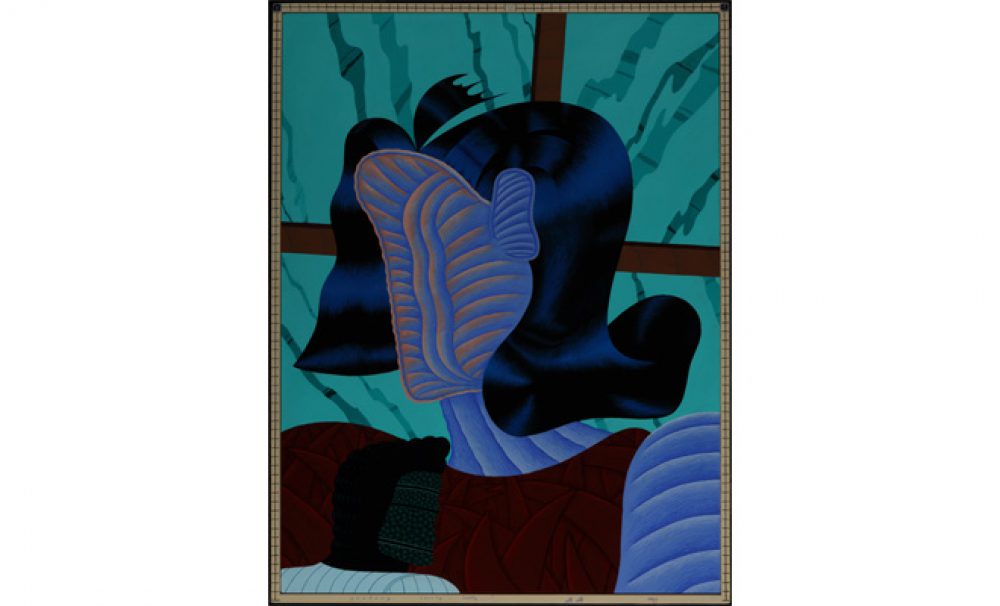

Jim Nutt, Sliding, Slowly, Softly, 1972. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy the artist and the New Orleans Museum of Art; Museum purchase, N.E.A. Matching Grant.

Editor's Note

"Brilliant Disguise: Masks and Other Transformations" on view through June 16 at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans. The exhibition is curated by Miranda Lash, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the New Orleans Museum of Art, as part of the NOMA→CAC initiative.