Moloch on the Banks: AnnieLaurie Erickson and After-Imaging

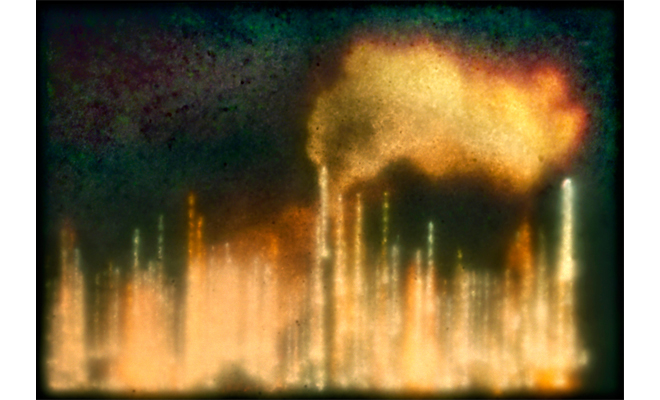

AnnieLaurie Erickson, 30°28'5.88''N, 91°12'37.73''W (Port Allen), 2013. Archival pigment print from color negative taken with after-imaging camera. Courtesy the artist.

More than a dozen massive petrochemical plants dot the banks of the Mississippi River south of Baton Rouge, an area the narrator of William Burroughs’ 1959 novel Naked Lunch describes driving through after scoring a liquid opiate in Houston: “We pour it in a Pernod bottle and start for New Orleans past iridescent lakes and orange gas flares, and swamps and garbage heaps, alligators crawling around in broken bottles and tin cans...” The refineries belch benzine and other carcinogens into the atmosphere and many spent decades pumping unadulterated waste into the river and surrounding bayous. In September 2010, a plant mishap sprayed 19 tons of “spent cracking catalyst” powder over the communities downriver from New Orleans, a synthetic volcanic eruption of sorts that coated homes, cars, streets, and lawns in mysterious white chemical dust.

Refineries such as these occupy a distinct space in our built environment and have inspired artistic imaginations. In his dystopian 1982 film Blade Runner, director Ridley Scott included them as prominent components of the Los Angeles skyline in the year 2019, in which the film is set, mechanized minarets with lights glaring through the haze of perpetual smog and rain. Filmmakers have long imagined the hellish effects of industry encroaching upon cities, perhaps first explicitly envisioned by Fritz Lang in his iconic 1927 film Metropolis, in which the hub of a factory beneath the city transforms into Moloch, a pagan god that demands human sacrifice. But refineries today remain, for the most part, in rural areas, encountered by city dwellers only on trips into the countryside, where the facilities rise along lonely highways like alien cities, their size and complexity enrapturing for only a moment before we pass them by. They demand sacrifice not in the ravaging manner of Lang’s Moloch, to whom workers are fed through his gaping mouth into his flaming gullet. Instead, the sacrifice is slow, taking the form of bone cancer or asthma or communities displaced by industrial expansion spurred by our lust for energy and oil.

AnnieLaurie Erickson, who moved to New Orleans in 2012 to teach photography at Tulane University, has spent the last several years using specially made cameras to capture images of unseen elements or typically unphotographable phenomena. In 2010, prompted by her feelings of paranoia about harmful emissions from cell phones, she undertook a project for which she photographed gamma radiation still seeping from ground at the site of the first manmade nuclear reaction, which took place in 1942. Two years prior, Erickson had been struck by a taxicab in Chicago that broke her leg and knocked her unconscious. It was a bright day, and when she came to after a long period of time with her eyes closed, intense sunspots on her retinas clouded her vision. She became obsessed with replicating retinal afterimages—the slowly dissipating light we can see after looking at bright objects and then shutting our eyes—and with the help of a collaborator built a camera that could accomplish this. The unwieldy instrument—for which Erickson and her collaborator crafted artificial retinal membranes from hydro-polymer material embedded with different colored particles of strontium aluminate—confined the artist mostly to her studio, from which she shot the sun and landscape out her window. The images from this body of work, titled Maunder Minimum, are ghostly and beautiful, but lack a unifying conceptual framework beyond the artificial emulation of an organic visual process. They suggest a novel photographic method in need of more considered subjects.

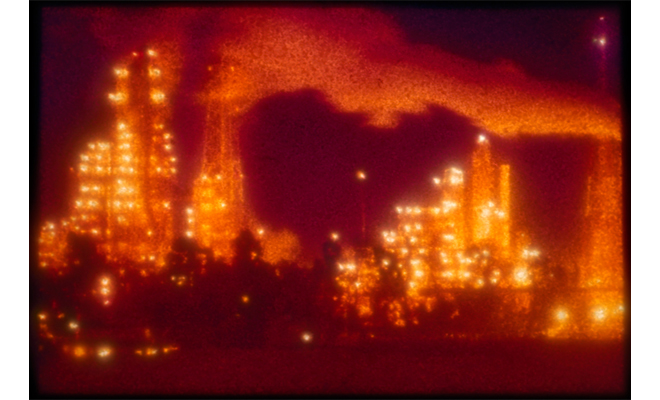

This month, Antenna Gallery is exhibiting “Slow Light,” a new body of Erickson’s work for which she used a more portable version of the retinal afterimage camera to make photographs of refineries, and in doing so leveraged the method’s strengths. The bright, surrealistic images remind one of Blade Runner’s cityscapes, but unlike the fictional film set in the future, they are pictures of our real dystopian present. The haunting effects created by Erickson’s special camera give the refineries a mystical quality, their blurred, distorted edges reminiscent of phantoms or ectoplasm revealed—fraudulently or not—in spirit photographs of the early 20th century. Erickson has said her artistic interests often center on using photography to extend the capacity of our vision, which is precisely what occult photographers intended to do by using cameras to capture images of ghosts called forth by mediums or séances. But instead of men with moustaches and bowler caps sitting around a Ouija board on a wooden table in a dark parlor, the conjurers of Erickson’s spectral refineries are everyday citizens pumping gas, switching on air conditioners, and buying plastic.

Many of the photographs in “Slow Light” focus on individual aspects of the refineries’ functions and characteristics—a close crop of a gas flare or a smoke stack bellowing vapor—but others show the complexes from a broad vantage that accentuates their size and setting. Shadowy trees and the gleaming Mississippi River foreground several of the shots and remind the urban art consumer how far removed these menacing structures are from the metropolises they resemble and feed. Each photograph’s title is its subject’s geographic coordinates—29°55'28.56"N, 89°58'48.87"W (Chalmette), for instance—calling attention to the refineries’ existence outside our civilian categories for organizing space. However, their distance from the city was the smallest obstacle Erickson faced in photographing them—early in her project, she was accosted by a police officer who told her taking pictures of refineries is illegal according to post-9/11 laws. Although the cop was mistaken—nothing in the Patriot Act even mentions photography—police regularly use the set of antiterrorism regulations as a pretense to harass and detain photographers. Erickson’s encounter only encouraged her to covertly continue photographing these “unphotographable” subjects.

The painterly attributes of Erickson’s images contrast the technological aspects of her method and subjects. Splotches, muddled lines, and emphasis on light give them an impressionistic quality, and the way in which the glowing refineries loom against dark backgrounds evokes the painted monsters and horrors of Francisco de Goya or Francis Bacon. The real dangers the refineries pose by poisoning air, water, and soil—and contributing to the climate change and coastal erosion that will one day drown them—are absent in any literal sense from the images in “Slow Light.” These themes exist in the realm of environmental documentary, while Erickson’s work is something else. Although the retinal afterimage camera simulates what happens when we close our eyes, to look at these images feels instead as if a curtain is being pulled back, revealing a world that strikes one at once as alluring, terrifying, and true.

AnnieLaurie Erickson, 29°59'23.45''N, 90°25'19.35''W (Norco), 2013. Archival pigment print from color negative taken with after-imaging camera. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

"Slow Light: New Work by AnnieLaurie Erickson" on view through August 4 at Antenna Gallery (3718 Saint Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.