A Grotto: South Louisiana’s Inner Space

For wherever your weekend might take you, composer, artist, and writer Philippe Landry reflects on a disappeared landmark.

The grotto once existed somewhere between Lafayette and Breaux Bridge on Salt Mine Highway.

French painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet and Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Béla Bartók were concerned with the unseen and the unheard. Mental hospitals and isolated ethnic enclaves provided the basis by which these artists independently sought to analyze and catalogue new forms and languages not then taken seriously by the academy. The music and drawings of mental patient Adolf Wölfli and the Slavic folk musics of the Carpathian Basin and Bohemian Forest were examples of people and spaces in which the idea of deviation could be applied to the problem of working within an established form or system. The untouched became stepping stones for a new aesthetic language in the twentieth century.

Down the bayou from New Orleans, around the crux of St. Martin, St. Landry, and Lafayette Parish, there exists a structure. I happened upon it nine years ago somewhere between Lafayette and Breaux Bridge on Salt Mine Highway. It appeared suddenly, seemingly floating in the night: a doorway filled with glowing statues and sparkling mosaics. In daylight it was revealed to be a grotto in the front yard of a doublewide trailer. French postman Ferdinand Cheval instantly came to mind.

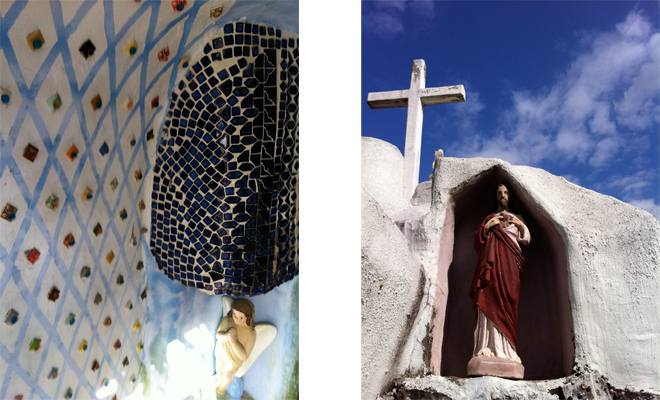

The structure resembles an igloo with a tiki hut in front of it and a crèche to the right of it. Made of hand-formed concrete, its outside is adorned with small toys, figurines of animals and people, glass beads and shards, magnetic letters, and porcelain mosaics. On one side is a fake metal tree with little porcelain birds and other bric-a-brac making their homes in its branches. A deer and the Virgin Mary are perched atop its dome. The tiki hut is adorned inside with glass beads, glass mosaics, and a ceiling bearing a hand-painted sky, the center of which is marked by the christogram “IHS,” meaning Iesus Hominum Salvator or the “Holy Name of Jesus.” Next to the iron-gated door is a plaque dedicating the grotto to the “victims of abortion.” The entire structure is strikingly formless in its execution, with no real fixed architectural language or temporal theme. In one sense it looks like a traditional Roman Catholic grotto found in churches and on church grounds the world over, with slabs of stones used to imitate a sense of antiquated ruin. In another sense it resembles structures found between North Africa, Southern Europe, or the Eastern Mediterranean, with a white plaster-like surface and repeating deep blue Byzantine mosaics not unlike the kind you might see in the arid landscapes of Sicily, Alexandria, or Athens. At the same time the design and maintenance of the structure allude to the South Louisiana Catholic tradition of cleaning and repainting family graves on November 1st, All Saints' Day.

The grotto is a summation of South Louisiana’s inner space. With a heritage of devotion and ritual tied to the land, the area holds many similarly preserved forms and structures. Isolation no doubt contributed to these unique forms and their preservation, Acadiana having been long buffered by miles of bayous, rice and crawfish fields, and the Atchafalaya. But as infrastructure improves and South Louisiana opens up to a greater outside population with an ever-increasing interest in its culture, inner Louisiana faces the danger of extinction or assimilation into mass American culture. As of the writing of this article the grotto has been demolished and the property sold. On my last visit, there was a couch being stored inside of it. Sacred space had given way to storage space. Or maybe just apathy.

Editor's Note

For a virtual tour of the grotto, watch Landry's digital video.