On Light, Falling: Virginia Woolf, Joaquín Sorolla, and Sally Mann

The summer heat still lingers in New Orleans, and Laurence Ross reflects on three artists’ attempts to capture the haziness of the season.

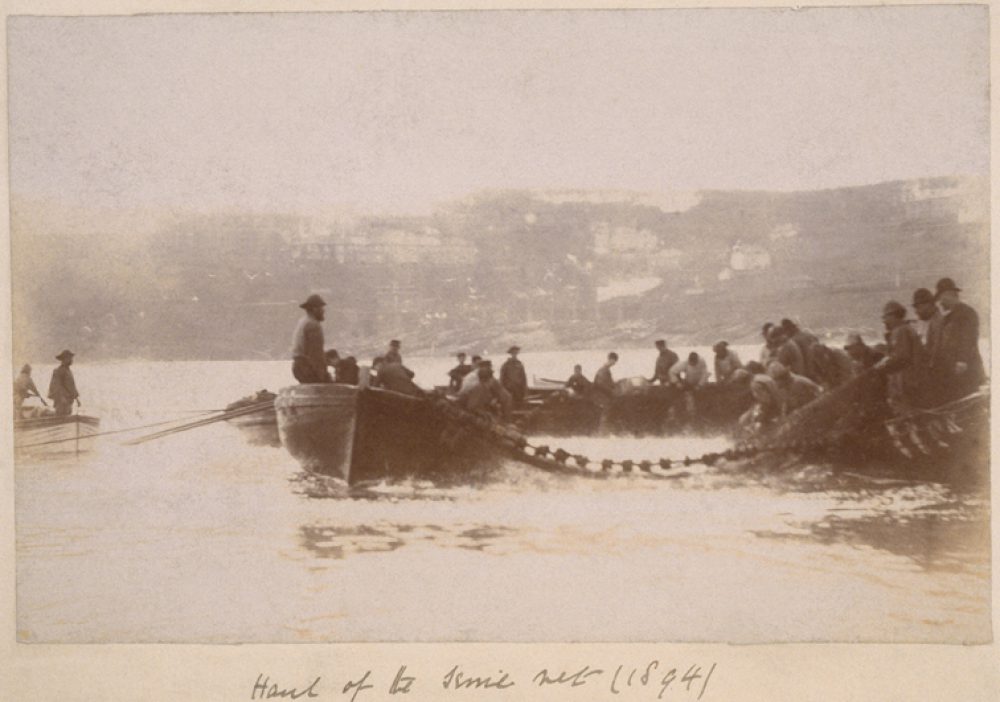

A photograph of St. Ives Bay by Leslie Stephen, Virginia Woolf’s father, from 1894. Image via Smith College Libraries.

Words belong to each other, although, of course, only a great writer knows that the word “incarnadine” belongs to “multitudinous seas.”

Virginia Woolf, “Craftsmanship”

Allow me to begin with a confession: this essay was originally conceived as a romantic musing on summer light in art, and it would perhaps be more convenient if it were summer still. In the late-June heat of New Orleans, I thought of a young Virginia Woolf at the beach. Then the summer paintings of Joaquín Sorolla, for they are also splashed with light and family, waves and play, depictions of seaside moments. Then, with summer family portraits on the brain, the photographs of Sally Mann came to mind. Now October, I attempt to remember all I had set out to accomplish here.

“Unfortunately, one only remembers what is exceptional,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her autobiographical essay “A Sketch of the Past,” and consequently many of her first memories circle around St. Ives—her family’s summer seaside residence, a departure from her London life. When setting down to write about herself at the urgings of her sister, Woolf attempted, as many memoir writers do, to begin at the beginning. But summers, like memories, are often hazy. They seem to linger on and on; they seem to slip away in a blur.

“A Sketch of the Past” was not published during Woolf’s lifetime. In the piece, in classic Modernist style, she quickly abandons traditional narrative in favor of a more impressionistic rendering. In dots of scene and dabs of sentences, she moves from one place in time to another, her memory a stone skipping. There is a relationship among these scenes, of course, though they seem to strike like sudden storms. Woolf curiously remembers the hum of the garden bees quite vividly, and “forget[s] completely being thrown naked by father into the sea.” That a sound of a bumble bee is more exceptional (and therefore memorable) than raucous ocean play shocks not only the reader, but Woolf herself.

Though these summer scenes did not make up the majority of Woolf’s childhood, they are what come to mind when she tries to remember. Her very first memory took place on a train or an omnibus: “This was of red and purple flowers on a black background—my mother’s dress...Perhaps we were going to St. Ives; more probably, for from the light it must have been evening, we were coming back to London. But it is more convenient artistically to suppose that we were going to St. Ives, for that will lead to my other memory, which also seems to be my first memory.” Her vision, and the scene, are cropped not because she could not fill in the gaps with her imaginings but because that is all she can see: light playing on the figures of flowers against a backdrop that takes up the rest of that space.

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Boys on the Beach, 1909. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

In 1909, Joaquín Sorolla painted Boys on the Beach, one of his most famous paintings and the only one of his Valencia seascapes hanging in the Prado in Madrid. At four-by-six feet, Boys on the Beach is imposing. When considering that Sorolla painted the piece on site, without a previous study, the work is even more impressive. Sorolla cropped the top of the scene well below the horizon, and our vision is immersed in what would otherwise be foreground in a painting with a wider field of vision. Light skims along the surface of the sea, the sand, and the bodies of the boys. We have an understanding that the scene is larger, for it must be. But three boys on a blue-mirrored background (that does indeed begin to incarnadine) fill the entire fabric of the piece. The boy in the top left of the canvas seems particularly content to examine the dark reflection of his own face in the shallow water (or perhaps what lies beneath it), allowing the sea to sink his limbs further into the soft sand—absent-mindedly content to become further embedded in summer. Sorolla painted the canvas as if a glossy film were wrapping it all up to save for later use, when the memories of summer and sun and this carefree spirit had cooled and faded.

Representative of Sorolla’s other major motif in his Valencia series, Walk on the Beach was painted between that same late June and late September: two women—his wife and his oldest daughter—in billowing white, with wide-brim hats and a sun umbrella, promenading along the edge of the surf. The whites are as gradated as the light on the water, and again Sorolla has cut off our view of the sun in the sky. During a midday moment, the sun is static in its place compared to the show of light and shadow going on below. It is on earth, not in heaven, where Sorolla found the exceptional. The sky and the predictable arch of the sun were of no interest to him and therefore we do not see it. What enraptured the painter was how the scene played out below.

As in her first memory, light plays a prominent role in Woolf’s second early memory as well. She is “half asleep, half awake, in bed at the nursery at St. Ives,” listening to the waves falling over and over again outside the window as well as to the sound of a little acorn attached to the end of a window blind cord scuttling across the floor in a breeze. She describes the feeling of these sensations as ecstasy, a word that seems surprising, given the seemingly banal nature of the scene. When revisiting the memory for a second attempt, she writes of “the feeling, as I describe it to myself, of lying in a grape and seeing through a film of semi-transparent yellow.” This description calls to mind a premature infant in an incubator, experiencing the sensory world at a remove—a distance that one perhaps needs from reality in order to truly remember. Or think of a tadpole still in its egg, biding time in that isolated globe, content to be coddled and yet viscerally aware of a larger life calling beyond the bubbled wall. How does Woolf feel—and preserve the feeling of—ecstasy within that film? And what causes her to attach more significance, more of the exceptional, to lying in that grape of a nursery than being thrown by her father into the ocean?

Sally Mann, Deep South, Untitled (Avery Island Road), 1998. Gelatin silver print. © Sally Mann. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian, New York.

Woolf revels in the summer memories she can recall but also regrets the loss of those she cannot. Whether or not Sorolla’s task was to cast a quick, wide net of brush strokes over vibrant summer scenes to crystalize their essence, I do not know. But capturing the fraction of a Southern summer second does seem to be what photographer Sally Mann was up to in the 1980s and ’90s with her own family portraits. As she writes in her 2015 memoir, Hold Still, she, like Sorolla, would haul her own cumbersome artistic medium—a large-format camera—through the trees and the river to the site of her subjects. “At the farm, the honeyed September light and the lazy, limpid river offered, as always, the cure, the balm for my bunged-up soul.”

What we learn through Mann’s writing is that the balm for her soul was not so easily captured as her photographs, or the lethargic air in which her subjects seem to reside, might suggest. She reveals: “When I sensed that a good picture lurked just beyond my range of vision, I went after it with dogged intent.” A photograph of her daughter Virginia posed with her hands above her head and ropes of wet, wavy hair mimetically pressed against her ribs can coax us into thinking of the image as natural if not effortless. In Hold Still, Mann reveals process in all its tedium: day after day, mossy rocks and inconvenient canoes, impatient clouds juxtaposed with one patient child. In the image she titled The Last Time Emmett Modeled Nude, 1987, her son stares at the viewer, head tilted ever so slightly downward, giving his gaze a cagey look, a look that suggests there is much stirring beneath that brow. Compositionally, the photograph creates a vanishing point behind the boy’s head, the Vs of the tree-line and its reflection drawing together, the smaller Vs formed by Emmett’s body and his hands barely skimming the surface of the water little echoes of those larger shapes. Prior to reading the memoir, I would never have guessed that the making of this photograph began in “balmy September” and ended in October, “in the freezing river,” “Emmett, shaking with cold.”

According to Mann’s account, the photographs that did come easily were as spontaneous as the title of her collection Immediate Family implies. Contrasted with the demands and failures that preceded the painstaking images, these other sort Mann refers to as gifts. Perhaps these fleeting compositions of family and food and light are the ones in which Mann experiences something of the ecstasy Woolf recalls in her second early memory, preserving these moments in yet another sort of film, “the breath-bated moment, a tenth of a second with the expansive, vertiginous properties of Nabokovian timelessness, while before me the brilliant angel no longer radiant with the sun snatches up the towel and heads to the beach, the tomatoes are imperfectly carved up for supper, and my heart, my pounding heart, sends from my core the bright strength for me to rise.”

Our experiences are embedded in the weather, though we rarely think of it in quite that way. Summer, and its light, has drawn Woolf, Sorolla, and Mann together into this wispy web of an essay. Though light is a force all three artists have reckoned with, it is not the only force. A season, and a scene, is more than light and shadow and reflection. During summers in the South, the air is thick. We feel the film of air on our skin, and though there may be sweat or river water or sea foam, there is more to it than that. The molasses-quality of high humidity can suspend, can hold, a landscape of color and sound, movement and memory. For many of us in New Orleans, we are ready for summer to be over, for the air to break apart, for the weather to realize the equinox has come and gone. But Woolf, Sorolla, and Mann experienced an intangible, ineffable something that, if it could not be fully captured, at least deserved a sketch of words, a streak of paint, the flicker of a shutter—an attempt. When Mann shifted her focus from her family to the Southern landscape itself, she set out to uncover the mystery of a place in time: “To whatever extent it is possible to photograph air, I was going to try to do it.”