On Flatness and the Faerie Realm: Andrea Dezsö at Newcomb Art Museum

Laurence Ross looks at Andrea Dezsö’s interpretation of the Brothers Grimm and other tales in her exhibition at Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Museum.

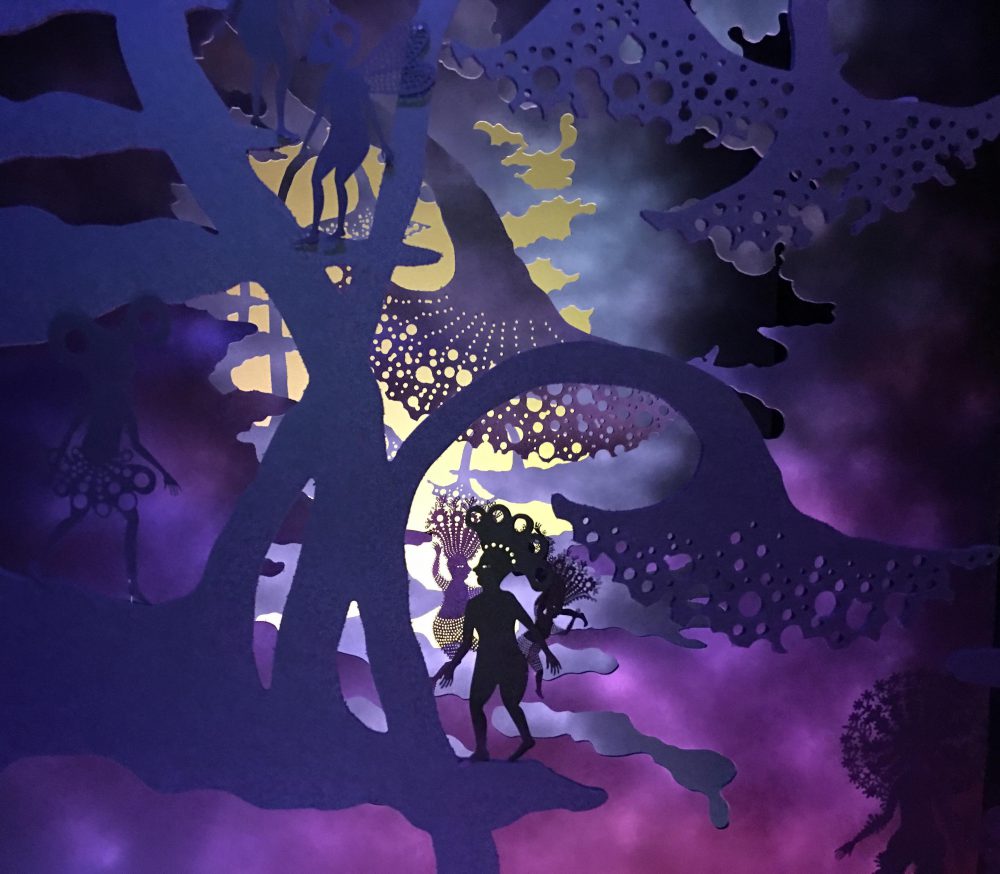

Andrea Dezsö, Krewe of Intergalactic Women Travelers Reach a Cave in Outer Space, 2016. Gator board, wood support, theatrical gels, laser-cut Bristol paper, acrylic spray paint, fabric, florescent lights (detail). Photo by the artist.

There is a story about a princess who is so preoccupied with a little golden ball that she ends up with a frog in her bedroom. The Brothers Grimm seem to have a penchant for open metaphor—tales which ring true because we fill in the white space with our own dark matter.

Yes, fair enough, but first fetch me the golden ball. I promise you everything.

The Princess

Andrea Dezsö’s art also places us in the realm of the fairy-story. Whether embroidery, ceramics, marker drawings, or a tunnel book constructed, cut, and sewn from handmade Japanese Shojoshi paper, her pieces work to collapse the worlds of fantasy and reality. As these worlds are woven into one foreign yet utterly habitable landscape, we can—and do—insert our images, our hopes and regrets, our loves and fears into the spaces in-between. It is in these spaces that our imaginations can run rampant along with these wispy-haired girls, creatures with sharp teeth and beaks, proto-humans with lulled eyes and opaque intentions; it is these spaces that we can fill with our own slim narratives, our own narrow meanings.

In an installation at Tulane City Center, Dezsö’s golden figures march with wings, antennae, scales, and fur, donning petalled clothing or elaborate headdresses, in a parade across cheerful, rolling hills. Rendered in a window decal, flower heads float in the air as this alien version of a 16th-century English masque moves across the glass front of the building. The echo of Mardi Gras is inescapable, and, though the silhouette-styling recalls Kara Walker, the play here is lighthearted. Much like the readers of fairy-stories, the spectators can do as little (or as much) work as they desire. The installation is a two-dimensional artwork that you can literally pass through (and therefore inhabit); just walk through the building’s front door.

Wait, princess, take me with you the way you promised!

The Frog

In her ink and paper illustration for “The Frog King, Or Iron Henry,” by the Brothers Grimm, on view in “I Wonder” at Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Museum, Dezsö draws the dark silhouette of the princess, suspended horizontal in the air. The princess reaches her hand through the surface of a pond—the dangerous, mirrored water that has caused so many a downfall—and, upon entering, her hand transmutes from black ink to white cavity, reaching phantom fingers toward the expectant frog, her handsome prince who has yet to take on a recognizable shape. The drawing is divided, and each side of the water is given equal space, the black and white of a singular reality.

Installation view of Andrea Dezsö’s site-specific vinyl mural at Tulane City Center, New Orleans. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Jeffery Johnston.

If Dezsö does indeed collapse realms that are often thought of as distinct and isolated, her work shares the characteristics of—and is in keeping with—the rich (if sometimes belittled or ignored) literary tradition of the folktale. Scholar Max Lüthi suggests that the genre is characterized by a “depthlessness,” a flatness in which characters lack psychological complexity, with plotlines in which motion is more important than motive. When describing the function and significance of the folktale, Lüthi writes: “Its sharp outlines and clarity of form and color go hand in hand with its emphatic refusal to explain its operative interrelationships in dogmatic terms.” In other words, a sense of adventure becomes the primary concern, morality falling second.

You must keep your promise no matter what you said. Go and open the door for the frog.

The King

Upon first glance, these characteristics seem to prohibit the existence of metaphor, as flatness suggests that there is nothing to unpack. But what seems more accurate is that there is no one thing to unpack—rather, we can unpack over and over again, conjuring up new meaning with each iteration, a tarot deck that offers up surprise with every reading. “Both clarity and mystery are integral parts of it,” says Lüthi. The work of metaphor is the practice of perspective. What is there to interpret here? What deserves my attention right now? What have I been ignoring? We work to understand our existence in a new way. We prepare to understand what has happened to us or what might happen to us next.

But the frog didn’t fall down dead. Instead, when he fell down on the bed, he became a handsome young prince. Well, now indeed he did become her dear companion, and she cherished him as she had promised, and in their delight they fell asleep together.

Surprise is a key element of Dezsö’s large-scale installation Krewe of Intergalactic Women Travelers Reach a Cave in Outer Space, which spans an entire wall of the gallery and is constructed of laser-cut Bristol paper, gator board, wood support, acrylic spray paint, theatrical gels, fabric, and florescent lights. Dezsö creates two separate caverns for the eye to enter, though the viewer is forced to choose one at a time. The work tunnels. There is an element of exploration, of discovery, of turning corners. The layered construction encourages multiple viewings. There is no single angle at which one can see the entirety of the piece, which seemingly contradicts our conception of paper as more or less two-dimensional. If viewing the work in a photograph, it would be easy to be fooled into thinking of it as a pair of colorful prints. But revisiting these scenes from various viewpoints can illuminate what had previously been hidden from sight, can spark some new glimmer of form or function, with fact and fiction settling comfortably on a single plane.

Andrea Dezsö, Krewe of Intergalactic Women Travelers Reach a Cave in Outer Space, 2016. Gator board, wood support, theatrical gels, laser-cut Bristol paper, acrylic spray paint, fabric, florescent lights (detail). Photo by the artist.

Krewe of Intergalactic Women Travelers Reach a Cave in Outer Space is inspired by the drawings of Carlotta Bonnecaze for the 1892 Krewe of Proteus parade floats and costumes. The theme that year—“A Dream of the Vegetable Kingdom”—tickled Dezsö’s senses. Dezsö says in an interview with Newcomb’s Director, Monica Ramirez-Montagut: “These drawings are artifacts that point to a lot of different things and everything they point to—imagination, play, devotion, community, visual abundance, making, improvisation—I’m interested in.” In Bonnecaze’s drawings, children pop out of peapods, a Faerie queen is pulled in her daisy-chariot by beetles and cockroaches, enormous dripping mushrooms draw sprites and snails alike, and waist-high strawberries are a cause for celebration. Proteus, the shape-shifter, seems a fitting muse for these large-scale cut-paper installations. For just like Mardi Gras or any large-scale party, just as with any prolonged parade of floating dreamscape, the lows become high or the highs become low, and we are asked to reassess the moment. We are asked, like the metaphor, to lean one idea against another in the hope that some new logic emerges. We ask: Just where are we standing now?

Editor's Note

“Andrea Dezsö: I Wonder” is on view through April 10, 2016, at Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Museum.

Quotations are taken from “The Frog King, or Iron Henry” in The Original Folk & Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition, translated by Jack Zipes and illustrated by Andrea Dezsö.